Out of thousands of named saints (and millions more unnamed saints), Catholics honor three dozen (and counting) as doctors of the Church. These great teachers of the faith have left us a heritage of profound theology that we should consult before we reinvent the wheel or steer ourselves into a ditch.

This series, Strong Medicine: Scrips from the Doctors of the Church, is one effort to retrieve and build upon their work for the Church today. Many doctors provoke little controversy. Augustine, on the other hand, elicits some unflattering reactions, even at a distance of some 1800 years:

- He cruelly abandoned his paramour, the mother of his son.

- He took his time converting to Christianity, then published an autobiography so effective at self-glorification that we are still talking about him today.

- He polluted religion with pagan philosophy.

- He couldn't separate his theology from his sex life.

Ensured Malpractice

When technicians report "operator error" as the cause of a computer problem, the user objects; we non-specialists want to pin problems on bad design, not on ourselves. For Augustine, however, operator error is the very condition of humanity and a key to his theory of everything: Thanks to Adam and Eve, human beings are in a state of original sin. Like lost phones bereft of chargers and batteries, human persons cannot even recognize their desperation, much less take steps toward a remedy.

You are not exempted by your race, sex, class, beliefs, or "being a good person." We are all in the same doomed boat of guilt and concupiscence. Before Christ offered any way to fix it, explained Augustine, "The whole mass of condemned human nature lay prone in evil, indeed, wallowed in it, and precipitated itself from one evil into another."

Unlike his non-Christian contemporaries, Augustine did not think of this doctrine as offensive. On the contrary, he experienced it as indisputable and liberating - indisputable for anyone who has bothered to examine his conscience or read a history book; liberating because it frees people from the impossible mandate to live a flawless life.

It is also a beautiful doctrine. Humans lacked the wherewithal to redeem themselves and didn't deserve to be saved, but the Son of God took on the project anyway out of pure love! This is totally unexpected and wildly romantic! As it says in the Exultet: "O happy fault, that earned so great, so glorious a redeemer!"

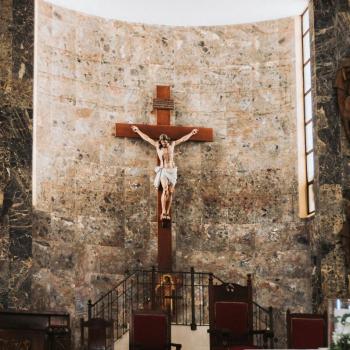

Like Augustine's sparring partners, today's Christians are tempted to downplay or deny original sin in some misguided body-of-Christ positivity. Augustine would be completely perplexed at this, and he might wonder if all his manuscripts had been lost to us. Why would people who are not utterly sinful require the drastic remedy of a God-man dying on the cross for them? Without original sin, the whole project of Christ's death and resurrection seems a total overreaction, like amputating a leg on account of a bad knee.

Augustine refined the Church's doctrine of original sin in hot disputes with Pelagians, those Christians who wanted to save themselves by their own bootstraps. He refined it further when the Donatists, a sizeable group of schismatic Christians in North Africa, refused to recognize the legitimacy of sacraments administered by compromised ministers.

His rebuke to both groups was essentially the same: Stop asking people to be God. God's grace is absolutely unmerited and unmeritable; humans cooperate with God's initiative, but they can never effect their own redemption. If things depend on us, one might as well despair. If the Donatists had produced even one truly sinless minister, perhaps Augustine could have been persuaded. God, not humanity, is the one who is faithful and perfect.

The Baby and the Bathwater

With the errors of the Donatists and Pelagians duly dispatched, the unity of Christians around the thought of Augustine was long-lived. Then, centuries after Augustine had become a dialogue partner through his works alone, Martin Luther encountered his emphasis on original sin.

Under Luther's Augustine-inspired protest banner of "sola fide" - by faith alone - some Christians marched right out of the Church. They were throwing out the quasi-magical, quasi-mechanical bathwater that many Christians were trying to use to clean their souls.

It is true that much of the flock had confused good works and rote prayers for justification and sanctification. But is the baptism of babies essentially an attempt to save ourselves? Is the changing of wine into the Blood of Christ a foolish human work?

Augustine, the very spokesperson for the utter inability of humans to merit grace, never conflated the heresy of self-redemption with God's saving work in the sacraments.

The Reformation Meets Twitter Meets Augustine

The Reformation protest movement can go by @SolaSolaFide, Catholicism can go by the handle @ExOpereOperato for an imagined Twitter battle:@SolaSolaFide: Can these members of the human race to whom God promised deliverance and a place in the eternal kingdom, be saved by the merits of their works? That is out of the question.

@ExOpereOperato: On the other hand, when a man is old enough to use his reason, beyond doubt he cannot believe or hope or love unless he wills to do so, nor obtain the palm of God's heavenly calling unless he decides to run for it.

@SolaSolaFide: The will of man alone does not suffice if the mercy of God be not also present.

@ExOpereOperato: But then, neither does the mercy of God alone suffice if the will of man is not also active.

It might shock Luther, but would not shock Augustine (who wrote every sentence in the Twitter battle above), to find out that Catholicism simply does not disagree with the 16th century reformers about the radical insufficiency of human merit to achieve salvation.

The sundering of Christ’s body would have dismayed him, and Augustine would well have wondered if his manuscripts had been lost or left not consulted. For that matter, Luther himself was confused that his contemporaries were lumping in the sacraments, which had been made by Christ, with shady man-made customs like building a monastery to shave years off Purgatory.

For both Augustine and Luther, in continuity with the tradition they inherited, when God offers redemption, He does it through the sacraments. He offered it to humanity through the work of Jesus Christ and that offer is continued in Christ's body, the Church.

The Incarnation is definitive of a new order, and it isn't over. Leo the Great, a doctor of the Church from the generation of theologians that succeeded Augustine, put it thus: "What was visible in our Savior has passed over into his sacraments."

When God elected to pour out the fountain of his grace with actual water in Baptism or to feed us with his real body, blood, soul, and divinity in the Eucharist, he did not make the offer contingent on a priest or any human being.

God makes the offer, and he makes good on the offer for he is faithful. The offer, not the experience, is what He guarantees. A sacrament is not the work of man.

Our Hearts are Restless

But what about the subjective faith-response of the believer? If the believer is distracted, or unbelieving, or weighted down by serious sin, how can we say that God's grace "works" through the sacramental form and matter?

In a sermon, St. Augustine gives us a vivid image of the role of the person in response to the offer of grace:

When people choose to withdraw from a fire, the fire continues to give warmth, but they grow cold. When people choose to withdraw from light, the light continues to be bright in itself but they are in darkness. This is also the case when people withdraw from God.

Sacramental grace is real because it is given by God, and its reality is not diminished by our distance from it. It comes through God’s creation, just as heat is given via fire. Humans are good at finding a million little ways to resist it, but Augustine would tell you to take it up with infinite gratitude.

Come close to the fire, come close to the light; receive forgiveness of sins, drink from the cup of salvation.

Stick to the Doctor’s Scrip

Augustine’s influence on Christian theology cannot be understated. Yet we keep in mind that the orthodoxy is not coextensive with Augustinian thought. Augustine would have lost some essay contests to other saints - to John Paul II on marriage, to Aquinas on the real presence, to Hildegard on music.

But oh, that he had been there to explain to Calvin and Zwingli that faith and sacraments are a package deal, and that it's a deal too good to pass up. And oh, that he had turned next to wayward Catholics to remind them of the magnificent truth which had routed Pelagianism and Donatism: Neither the I-can-do-it-myself believer nor the holier-than-thou minister is responsible for the grace of the sacrament.

The operator is Christ, the high priest, making Himself really present to His church in the ways that He Himself instituted.

Augustine was not there in the 16th century and is not here now, but he has hardly left us to our own (de)vices. We can read his writings at length, and we can ask his intercession:

St. Augustine, pray for us that we might be delivered from Twitter theology, that the wounds of disunity might be healed, and that we might all receive God’s undeserved grace as one body around the table of the Lord.

Kaitlyn Dudley Curtin holds graduate degrees in Theology and in Education. She writes a monthly column, “Strong Medicine: Scripts from the Doctors of the Church.” She keeps up a personal blog and recently contributed a chapter to Teresa Tomeo’s book "Listening for God." She and her school principal husband parent five lovely children in upstate South Carolina.

Do you have an opinion or in-depth response to something you’ve read? Please send us your written (or video) response to consider for publishing on Patheos. We are interested in sharing your perspective. Please note, we require civil discourse, focusing on the topic rather than a writer. We are looking for your faith-affirming, engaging thoughts.

9/14/2021 5:01:33 PM