Though Jerome excelled at translating Hebrew, Aramaic, Latin, and Greek, linguistic prowess did not make him a saint.

Jerome became a saint by devotedly seeking the Lord in the Old and New Testaments.

He knew that Christianity is only possible with valid knowledge of God’s revelation in His Son, and that the Bible is essential for such knowledge. True Christians let the Word dwell in them richly: "Ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ."

If you are reading a featured article from Patheos, you have little trouble accessing a Bible. For Jerome, however, access to the sacred page was complicated: the complete texts of the scriptures were not readily or reliably available in Latin, the common language of the fourth-century western churches.

Jerome concluded that the logical course was to learn the scriptural tongues. During a sojourn with desert-dwelling monks, he scraped together tutorials in Hebrew from an ethnically Jewish companion; throughout his travels, he took time to build on the Greek lessons he had taken in Rome; when given a moment to relax, he studied Aramaic instead.

Hiring St. Jerome

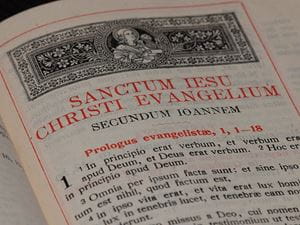

Eventually, Jerome would embark on an ambitious project to standardize the texts of biblical books in an authoritative Latin edition that we call the Vulgate. This intensive but beautiful endeavor would define the rest of his life.

This was no rogue enterprise, but one commissioned by the pope himself. Contrary to historical distortions, the Catholic Church wanted the people of God to have access to the scriptures for study, liturgy, and prayer.

How did Pope Damasus know Jerome was the man to spearhead such an essential work of the Church? After all, there was no university to credential Jerome, whose formal education as a young man had not differed from scores of secular writers. In the absence of an established licensing body, how could anyone be sure Jerome was qualified?

The pope had witnessed Jerome’s scholarly contributions to the work of a particularly contentious council. On the strength of that showing, he had hired Jerome as his personal secretary. Not all employment situations result in more trust from the boss. Jerome must have lived out a steadfast work ethic, a single-hearted devotion to the Church, and a genuine closeness to God that was unmistakable, even at close quarters. Perhaps the pope also judged that Jerome's famous stubbornness would be a strength when it came to the difficult work at hand.

The pope’s selection proved astoundingly successful. Long before the Church crafted an official process for canonization, the grateful faithful would acclaim Jerome as one of the eight original "doctors of the church."

Not Lost in Translation

What does it take to deliver an accurate translation of a sacred text? And what are the stakes?

Good translations can take years. The New American Bible, an English translation, was in progress between 1936 and 2010. Sometimes, good translations are not really possible because of the richness of the original terms - Latin and English texts, for example, include intact Hebrew and Aramaic words such as Amen, Alleluia, and Hosanna.

Bad translations can work a great deal of mischief. Paraphrase versions of the Bible, for example, risk over-simplification and give preference to an editor's doctrinal allegiances over the intention of the original author.

Good translators do their duty to the details. They err on the side of matching original idioms, images, and word order, even when doing so means a modern reader will need to rely a bit more on commentaries and notes. Their intimacy with the target language allows God's truth to shine forth in a new place and age.

In a sense, Christians in every age and place must engage in the work of “translating” the Bible. Like Jerome, we must make the Incarnation known in the language of our day.

Today, a revision of Jerome's Vulgate Bible serves as the typical version for the Roman Catholic Church's Latin Rite (non-Latin rites had far less need of Jerome's services). That means it is a benchmark to be consulted when scholars, in imitation of Jerome and in line with Church teaching, seek to refine translations from the manuscript traditions.

Inventing the Bible

Translation was hardly the only hurdle. In some cases, multiple manuscripts of the same book competed for preeminence. In other cases, scribes had rendered imperfect Latin translations that were in circulation but needed significant editing.

Moreover, the canon itself was a feature for debate. Modern people take for granted the existence of "the Bible," but the question of what is canonical is by no means a simple one. Which apostolic-era texts should count as sacred scripture? If a Hebrew manuscript of a particular book cannot be located, is the Greek recension legitimate, or should the whole book be tossed out of the canon? (And what happens when that missing Hebrew manuscript is found in a cave in Qumran more than a thousand years later?) How can the Bible serve as the rule of faith if it does not exist?

By the end of the fourth century, the Christian canon had been largely solidified. Some sacred writings had been deemed beneficial but not divinely inspired, while other writings had been excluded for giving inauthentic witness to revelation. Jerome weighed in on the canon - he became convinced that books such as Tobit and Judith were not on equal footing with the rest of the Old Testament. In intellectual humility and ecclesial obedience, he granted that he might be overruled by later ecclesiastical pronouncements. And indeed, the sixteenth-century Council of Trent formally included several works Jerome had doubted. Jerome did not turn over in his grave. He had performed his scholarship in service to the Church, which he believed rightly exercises authority over the canon.

As for the so-called Gnostic gospels, Jerome would have been aware of them and would have dismissed them the way that you dismiss strange diatribes from acquaintances on Facebook. Note: when modern enthusiasts tout the 'suppressed' wisdom of Gnostic writings, they consistently cherry-pick the most 'enlightened'-sounding passages, conveniently leaving out the bizarre and often incoherent teachings, e.g., that all people should abstain from all sex, and that Jesus' most essential teachings should be kept as secrets for the elite few. Don't take anyone's word on this - just go read the Gospel of Thomas or the Gospel of Judas for yourself.

Jeromian Objectives

The “doctors of the church” are preeminent teachers. If Dr. Jerome were in charge of your congregation's faith formation program, what would he propose?

Don't worry, I don't think he would make everyone learn Latin.

Here is an attempt to write some objectives he would approve and assignments to go with them.

Objective 1: Christians will discipline their minds.

Do mental concentration and intellectual rigor seem essential for a Christian life?

We lay people are not surprised to learn that a man with such a productive-sounding name as Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus (aka Jerome of Stridon) achieved great works of holy scholarship. But are we ourselves willing to undertake a strenuous effort such as learning another language? What about mastering three different alphabets? Our unspoken credo might be Scholarship for the thee but not for me.

To be sure, not every Christian has a scholarly vocation. Historically and globally, most Christians have lacked access to the training needed to make it past an academic journal's peer review process.

But every single Christian has a vocation to discipline her mind so as to better know, love, and serve the Lord.

Even if you think you can do without a well-informed, disciplined mind, consider the needs of others. Many Christians are disaffiliating from their faith tradition by their early teens. When queried, they point to insufficient explanations for how a good god could allow suffering and they express doubt that biblical faith could ever be reconciled with Science.

What? For centuries, Christians have grappled with these questions. Scholars and saints have said so very many cogent things on these topics that it is absurd to suggest otherwise - or is it? The disaffiliated might as well have said, "Our Christian community has utterly failed to hand on what it has received." If large numbers of individual believers neglect to make time to learn their tradition in any real breadth and depth, we should not be surprised when a more naturally skeptical generation abandons the bark of Peter en masse.

So get ready. Jerome does not attach short, well-produced videos to his parish-wide emails. Jerome is attaching PDFs of unabridged patristic treatises.

Your assignment from Jerome: Set aside more time to read - you'll need it.

Objective 2: Christians will remember the scriptures.

Imagine an elderly Jerome, at the end of his career, recalling the feel of ink and the smell of vellum. He breathes out the words of the psalms. He has by heart the stories his aged eyes now cannot read.

Imagine yourself, near the end of your life, recalling your memories. The plots of exciting movies mix freely with your authentic personal experiences. You can sing many song lyrics full of sound, signifying nothing. You would like someone to read the Bible to you, but you can't direct your visitor to any favorite passages, for you simply did not live your life in close touch with the word of God.

Jerome would want something better for us. He would want us to realize that Scripture is not something we leave behind once we have found a useful take-away; he would want us to attend to the same cycle of readings in liturgies year upon year; he would want us to dwell in it richly so that it could dwell in us. He would want us to tenderly love the sacred page.

Your assignment from Jerome: Choose a beautiful passage and memorize it. Jerome also recommends bringing a Bible with you on vacation and everywhere else.

Objective 3: Christians will not give up on the Church.

Jerome said, "The Church is the body of Christ, kept together by the bond of charity." The Church is the way Christ makes his incarnate love manifest in the world. Jerome stayed in the Church because of the holiness, perfection, salvation, and love of Christ, not because he was impressed with his fellow believers or clergy. Indeed, he was rarely impressed. When he lived in Rome, he made no secret of his disdain for the rich-living and corruption he perceived in many Roman priests; even St. Augustine disappointed him.

Jerome is a doctor of the Church because without him, the Bible as we have received it might not exist. But we need to know what he knew: that without a Church with the authority to pronounce which texts were inspired by the Holy Spirit and which were not, there would not be a Bible at all.

Jerome fought hard for unity in the truth, and he would be horrified by the modern proliferation of denominations.

Your assignment from Jerome: At the very least, trouble yourself to be troubled by the scandalous disunity among Christians. This saint would have us pray as Jesus prayed, as recorded by John and as translated by the doctor himself: Ut omnes unum sint - That they all may be one.

10/14/2021 5:26:29 PM