John Chrysostom had a gift for provocation. More than once, he goaded authorities into exiling him, and he died during an imperially-ordered one-man forced march.

Had Twitter existed in the 4th century, every Constantinopolitan would have followed @Archbishop_John – some ready to be chastened, some eager for indignation, some along for the spectacle of fearless zealotry. Consider these quotes, taken from his epic sermons:

“We must not mind insulting men, if by respecting them we offend God.”

“Not only was their doctrine Satanic, but their life too was diabolical.”

“I do not think that there are many among bishops that will be saved, but many more that perish.”

“Slander is worse than cannibalism.”

Chrysostom didn’t need Twitter. His three hours of Sunday preaching afforded plenty of platform, and his rhetorical skills attracted even his ideological enemies. The name Chrysostom was not a surname, but a nickname given him by the people: Golden-mouth.

John Chrysostom was talented, entertaining, even riveting, yes; but he was quite inconvenient. The empress Eudoxia, a devout but worldly woman, erected a statue of herself near the doors of John’s cathedral; the next week, John preached against making statues which vaunted imperial power in loco Christi.

If you haven’t encountered Chrysostom before, here is your trigger warning: prepare to be offended.

Offensive Idea 1: Your Personal Property Isn’t Really Yours

Chrysostom’s homilies about Lazarus and the Rich Man explode off the page. The modern reader might as well be standing in the front row of the cathedral. Picture Eudoxia’s face, framed by perfect hair and gorgeous jewelry, as he proclaims,

“For nothing --- nothing is worse than luxury.”

She wasn’t alone in her discomfort. John was calling out a much wider swath of society than the super-rich. The Catechism of the Catholic Church quotes Chrysostom to all of us: “Not to enable the poor to share in our goods is to steal from them and deprive them of life. The goods we possess are not ours, but theirs.”

John went on to use every rhetorical tool at his disposal to make his congregation feel this truth along with the shame of wishing it untrue. He wanted to see congregants weeping for the plight of the poor, beating their guilty breasts, and opening their purses to the needy.

Hearers knew he lived what he preached. As a young man, he had wrecked his own health in pursuit of extreme monasticism. As shepherd of a major metropolis, he could have lived in luxury and smelled like the (richest) sheep – many bishops have done so, though not without drama. He accepted no party invitations, he kept no fancy household, and he wore no expensive garments.

It is terribly inconvenient to the critiqued when the critic is not a hypocrite.

Offensive Idea 2: I Don’t Answer to You

The story of 4th century Christianity is one of crisis and intense controversy. Arianism and its many variants splintered the people and the fraternity of bishops, and the emperors made clumsy attempts at unity. From our 21st century vantage, the triumph of orthodoxy and the dominance of Byzantine Christianity seem inevitable; for John and his flock, everything was contingent and combustible. Indeed, if not for the indefatigable Athanasius (298-373), Arianism might have replaced orthodox Christianity altogether.

Chrysostom concluded from this mess that the flock does not know what is true or how to pursue it rightly. The role of the Church is not to take polls and have listening sessions, but to teach the truth, celebrate the mysteries, and care for the spiritual needs of sinners.

Late in his career, a group of theological opponents and disgruntled colleagues accused Chrysostom of various offenses. They charged him with such atrocities as dining alone and doing things without their permission, and they summoned him to an improvised meeting styled the “Synod of the Oak.” He didn’t come. He didn’t answer to them, either.

He answered to God and to God’s properly appointed minister in the seat of Peter, but not to fellow bishops, congregants, or the even the emperor.

This sort of thinking is noble and principled, but many of his contemporaries found it maddening, and many modern people find it paternalistic. Human objections never mattered to him, but only the ultimate judgment of the Lord God.

Offensive Idea 3: You’re Acting Too Jewish

The East persisted long past Rome’s fall in 476 until Constantinople’s fall to the Turks in 1453. Chrysostom served in two of its most important cities as bishop: Antioch and Constantinople.

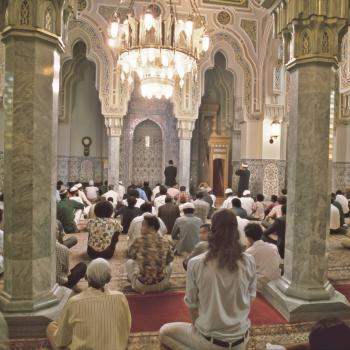

Antioch was home to a thriving community of Jews. Some Christians admired Judaism for being ancient and beautiful (which it was and is); some had never completely separated their religious practice from their ethnic Jewish roots; some intermarried with Jews; some tried to cover all their spiritual bases by engaging in practices of both Christianity and Judaism. Rancor between Christians and Jews did not prevail through all history: In Antioch some Christians were observing the fast between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, asking rabbis to bless their fields, and even attending synagogue services. Chrysostom could not take it for granted that his brand of Christianity was more attractive, stable, or popular than Jewish (or even pagan) options.

Disturbed by the syncretism, Chrysostom preached on the saving power of Christ. Like Paul, he worried that his flock was missing the point that “we have believed in Christ Jesus that we may be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law, because by works of the law no one will be justified.” (Galatians 2:16)

In one homily, he likened following Jewish law as a Christian to sitting next to a lamp when the sun is shining.

His homilies against ‘Judaizing’ practices are vitriolic and full of hyperbole for the same reason that a person suddenly and violently shoves a friend out of the path of an oncoming truck. Chrysostom believed Christians who sought an alternative path to salvation were in a more ultimate mortal danger than death: eternal damnation. No rhetoric seemed too extreme in the service of redirecting souls from the road to perdition.

Misinterpretations

Although Chrysostom was an incredible exegete, many of his interpretations regarding God’s Chosen People were deeply wrong. In his series Adversus Judeaeos, he proposed that the Jews as a people forever bear the bloodguilt of the crucifixion. He believed that God had rejected the Jews and had permanently exiled them from their homeland by the hand of the Romans.

Chrysostom was wrong to lay the crucifixion at the feet of the Jews. Our sins, the sins of the whole world through all time, led Jesus to the cross. “God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” At the Second Vatican Council, the Church proclaimed:

"True, the Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ; still, what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today… Christ underwent His passion and death freely, because of the sins of men and out of infinite love, in order that all may reach salvation."

Chrysostom was wrong to declare the Jews accursed. Instead, as the council fathers wrote:

"God holds the Jews most dear for the sake of their Fathers; He does not repent of the gifts He makes or of the calls He issues… Although the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures."

He also missed the mark regarding what Jesus was up to when he violated Pharisaical interpretations of Sabbath rest. Jesus did not jettison the law altogether; indeed, refraining from unnecessary servile labor on Sunday remains a precept of the Church. Chrysostom should have been more careful to distinguish moral and ceremonial law and to draw the connections between old and new practices.

Canons of the Canceled

Brilliant contributions often present as comingled with problematic interpretations of doctrine. Like his close contemporaries St. Jerome (347-419) and St. Augustine (354-430), St. John Chrysostom (347-407) was not a perfect thinker, especially when it came to Judaism and Jews. Indeed, many modern voices accuse Chrysostom of outright anti-Semitism. This is a very serious charge, especially in the terrible light of subsequent persecutions, pogroms, and the Holocaust which would not be possible without a teaching of contempt. If guilty, can he be rehabilitated, or must he be disowned? Does anything less than cancellation qualify as an elaborate game of make-believe at best, a dishonest whitewashing at worst?

Any sort of honoring – of the quick or the dead – asks us for precision and care that do not attend our everyday, casual interactions with the world. No man is without sin, yet bishops must be chosen; no woman since Mary has lived without sin, yet millions of children love their mothers. What is the threshold of flaws we ought tolerate? Should we refrain from honoring anyone since all fall short? Perhaps we should name our parks, buildings, and institutions after plants or abstractions rather than after sure-to-disappoint flesh-and-blood.

Our quest for a perfect object of admiration must aim at God who is and ever will be the only perfect thing in the universe.

Canonization is not the opposite of cancellation. It is not a stamp of infallibility on every word uttered, on every homily written, or on every action performed. To declare that a person followed Christ with heroic virtue and is now in heaven is hardly the same thing as to say that the person in question never sinned or never calculated incorrectly. Canonization does not define a particular doctrine, but rather brings us into relationship with a mentor.

The Church names saints and doctors of the Church as but one teaching tool in the context of larger lessons, so we the students still have much work to do. Inconvenient though it may be, the task for Christian believers is constantly to measure everything by the rule of faith. We do not slavishly trust any mortal’s wisdom, even those officially canonized as saintly mentors in faith.

Choosing teachers, mentors, heroes, and saints must be done with a forthright understanding that they will all be flawed. Their lives do not become exempt from critique, and their teachings do not become unquestionable. They must not be adored, but admired. Admiration fits in the ample space between cancellation and deification, and if we are to admire or learn from anyone at all, we must create and consider this space.

A key parameter to this space is our debt of gratitude: without the faithfulness of our flawed predecessors, there would be no faith by which to measure.

May disciples not grow weary of discernment, and may the Spirit guard our minds and hearts as we tirelessly walk the Way.

7/20/2022 9:46:06 PM