I’d never been to a retreat like this. This would be my first. I guess that’s not surprising given my late arrival to Catholicism, converting only four years ago. But now, my oldest daughter (a second-grader) was about to take part in her First Reconciliation. So I found myself on Saturday morning arriving with my wife and daughter at our church’s retreat to prepare for this Holy Sacrament. Starting us off, the deeply thoughtful yet puckish Director of Children’s Faith Formation, Andrew Allen, helped characterize for parents and kids the nature of this sacrament and why it matters. He led us in prayer and then sent us with our kids on our way to four stations dedicated to writing, coloring and acting exercises designed to more deeply consider the examination of conscience and the subsequent act of confession. It was a well-run retreat (how many retreats actually are?) being efficient, structured, instructive and sensitive to the needs of young kids who may be a touch nervous telling their not-so-dark deeds to a priest offering Christ’s absolution. So all in all, it was a good experience.

But then I arrived in the Confessional. Now I have to be honest, I haven’t been there in some time, but this is what I saw. The room was warmly lit with an overhead light and a lamp on a corner table. The door remained open to the comfortable neighboring chapel. The carpeting looked new and had that soft cushiony give when you stepped on it. The screen between priest and penitent partially bisected the room from the south wall, but a chair sat within view of the priest should that be the chosen form of confession. This was all well and good. A warm, inviting environment for what could conceivably be, especially in the eyes of a second-grader, a daunting task. But that is when I saw them. Three paintings. They were on the north wall opposite the screen so that for the entirety of the confession, the priest and penitent could fix their gaze on them. Three paintings from French artist James Tissot’s Life of Christ.

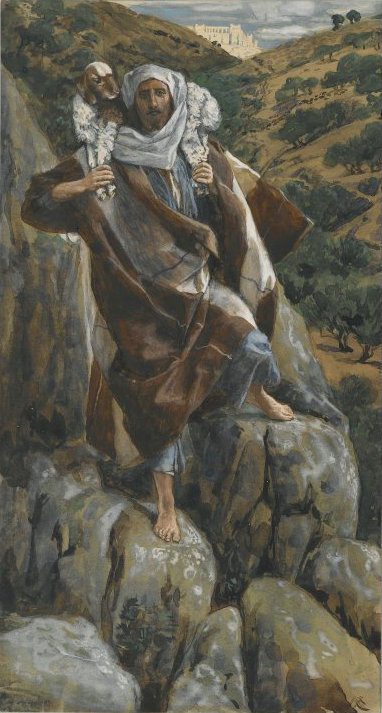

The Good Shepherd

The Lost Drachma (coin)

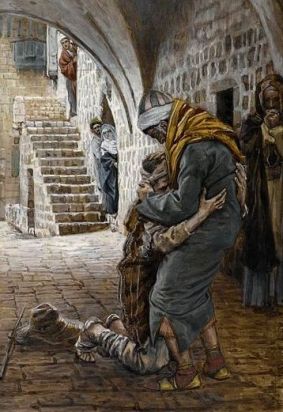

The Return of the Prodigal Son

You see, in that room warmly outfitted and comfortably attired for the sacrament of Reconciliation, all faded away for me except for those three pictures. In them I saw an absolute beauty. In them I saw limitless mercy.

My daughter, even in second grade, understands the fundamentals of God. She knows that God made her and her sister, that they are special and called to do great things, that Christ came, taught, died and rose again. They understand that he will return someday. These are truths she has learned from Mass, Bible stories and conversations in the car or at the dinner table. She and her little sister grasp these foundational truths with their innocent and inquisitive elementary school minds.

But when they look at these paintings, the rational conception of God is set aside and the visceral experience takes over. They can understand a God who would find it unthinkable to leave one stray sheep alone and vulnerable on the sharp, craggy cliffs. They can appreciate the back-breaking effort of a woman who refuses to abandon her search until the lost coin is accounted for. They can feel the ache and gush of relief of a son who got lost – really, really lost – but is reunited with his Daddy who weeps and weeps tears of exhausted joy. They don’t have to think about this. Perhaps they don’t even want to. They can feel it. And, sweet Jesus, does it feel good.

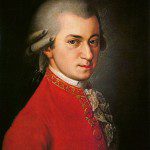

I recently watched one of my favorite movies, Amadeus. In this extraordinary film (which, yes, used a good degree of literary license with the facts) about Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the ambitious and thin-skinned composer, Antonio Salieri, finds himself utterly tormented at every turn by the success of Mozart. To watch helplessly as this young, handsome upstart genius Mozart, succeeds with music, women and powerful leaders causes Salieri to be relentlessly consumed with hatred and jealousy. But in the midst of the hellish sins of envy, rage, greed and pride, Salieri cannot help one thing. One thing that in spite of his best efforts keeps returning to him again and again and again. Mozart’s work is truly glorious.

Recounting to a priest how he looked at Mozart’s perfect handwritten first drafts of music, Salieri gripped his hands as if he were holding onto the bars of a prison and then concedes magnificently and undeniably,

“I was staring through the cage of those meticulous ink strokes – at an absolute beauty.”

Antonio Salieri, in spite of his bitter envy and hatred for the man that is Mozart, could not snuff out his honest appreciation of something that is transcendent, something that was, quite simply, beautiful.

And so it is with us. Through the cage of our sin, we can see the mercy of Christ. Through the bondage of our fallibility, we can grasp the liberating hand of God. And though in confession we burn and hurt when we are honest about our shortcomings, we can still see the God who is in search of us, the Father who embraces us so fiercely and so tenderly, the God who weeps for joy at our return.

My daughter’s First Reconciliation will be extraordinary. I know so. And I pray that she will get a glimpse, even if only a brief glimpse…of the sweetest mercy of Christ. A glimpse of an Absolute Beauty.