The ancient and cross-cultural belief that birds contained the souls of ancestors may have played a key role in one of the greatest adventures in human history – crossing the Pacific Ocean and populating the Americas.

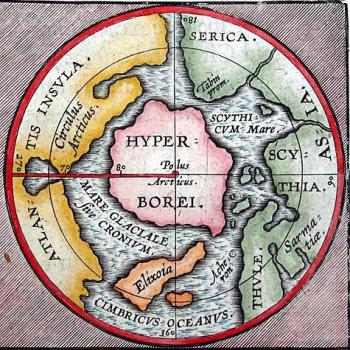

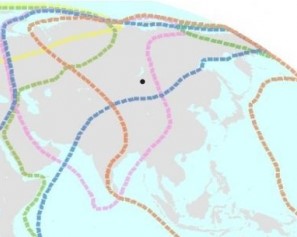

At least 14,000 years ago the closest known genetic relatives of Native Americans were living in Ust-Kyakhta, on the Russian side of the border with Mongolia, according to a 2020 genetic study by the Max Planck Institute. Ust-Kyakhta is located where three global bird flyways overlap, a rare global phenomenon that produces a huge and diverse avian population including more than a thousand different species.

Scholars long believed that human migration to the Americas occurred across a land bridge from Siberia to Alaska about 13,000 years ago, but the theory fell apart in recent decades when far older settlement sites were found throughout the Americas.

Scientific consensus is emerging around the Coastal Migration Hypothesis, first outlined in a 2007 study claiming that mariners could have used small boats to follow a kelp forest east from Kamchatka along the southern edge of a glacial ice-pack about 16,000 years ago.

The kelp forest and associated fisheries would provide enough food for the mariners all the way down the Pacific coastline of the Americas, helping to explain why one of the oldest human settlements in the Americas is in Patagonia.

A key addition to the coastal theory

A classic failing of western scholarship is to focus too narrowly rather than taking a holistic approach.

The kelp forest tracks exactly with the Pacific Ring of Fire, which perpetually up-wells minerals that feed the forest. It’s no coincidence that large migratory waterfowl such as ducks and black Brant geese follow migration routes from two different global flyways over the kelp forest, which is a valuable avian resource for rest and feeding. In turn the droppings from millions of migrating waterfowl help sustain the kelp forest.

Standing on the shore and gazing out to sea, what moved these adventurous mariners to get in their boats? Both the birds and the kelp forest would have been encouraging signs, but it’s likely the Asian mariners weren’t the first to follow migratory birds.

Bird migration maps compared to the human fossil record suggest every human-like species since Homo erectus followed bird migration routes, which never stray far from fresh water and abundant resources (including kelp forests). Birds also provide alarm calls when predators are near and exhibit a mass-scattering behavior when catastrophic storms are on the way.

One of the oldest and most common cross-cultural creation myths describes migratory birds delivering seeds to the land and in some cases literally creating the landscape. In eastern Siberia, the Koryak describe a raven god dropping a feather that created the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Modern science recently confirmed that migratory birds distribute enough exotic seeds over hundreds of miles to substantially diversify the flora on their seasonal grounds, according to a 2016 study published in The Royal Society of Biology, London.

From the viewpoint of our adventurous Asian mariners, the millions of migratory birds who flew away every year over the ocean and beyond the horizon were flying to a destination they had long ago seeded with life. Considering the same flocks returned back over the ocean every year, their destination must have been bountiful.

The spiritual evidence

Across Native American cultures in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, birds were believed to be vessels for the souls of ancestors, seeking to guide the living.

On Vancouver Island, Kwakiutl dancers used hidden strings to pull open an eagle-head mask and reveal the mask of a human ancestor inside. Living on the nearby archipelago Haida Gwaii for at least 12,500 years, the Haida people perform a similar dance using a raven mask. Another symbolic link to the world of ancestors was the eagle carved atop most totem poles.

The Serrano and Shoshoni of southern California say their ancestors came from the north, following an eagle to the San Bernardino Mountains, where the tribes settled. The Mojave of California and Arizona and the Apache of Arizona and New Mexico say their ancestors followed a hummingbird into this world by climbing a vine through a hole. (Some indigenous cultures represented time vertically; below ground was past and the sky symbolized the future.)

In Arizona, the Tohono O’odham once practiced singing treks, following the directions outlined in the verses of “The Oriole Song,” which guided them to dozens of sacred springs, caves, and mountains. The O’odham believed their singers learned the melodies of the travel song from birds that appeared in their dreams. Archaeologists identified many of the ancient trails and in March 2015 a group of O’odham men revived the ancient practice, making a 286-mile trek from southwest Arizona through lava fields and dunes to the sacred salt flats along the Gulf of California and back. The last verse of “The Oriole Song” conveys the sense of a journey’s end.

The songs are ending as they go their separate ways,

from the center of our songs the wind comes,

flowing back and forth,

erasing the tracks of the people,

ready to place them here again.

Settling with birds

Virtually all the oldest settlements in North America developed in two corridors running north to south – the same areas where two global bird flyways overlap to produce a greater number and diversity of birds.

In the west, the Pacific and Central Americas flyways converge in Alberta, Canada, heading south through Idaho, Utah, much of the Southwest and Texas. The converging flyways encompass Coopers Ferry, Idaho (16,000 years old), the Clovis culture of New Mexico (13,300 years old), the Buttermilk Creek Complex in Salado, Texas (15,500 years old), the Hohokam homeland in Arizona (4,000 years old), the Anasazi/Pueblo cultures of the Four Corners region (2,000 years old), the Fremont of Utah (1,400 years old) and a set of 23,000-year-old footprints preserved in White Sands National Park, New Mexico.

In the east, the Central and Atlantic Americas flyways converge from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast, encompassing the same vast area where Mississippian cultures shared similar beliefs and traded valuable religious artifacts. This region features the highest concentration of Native American mounds in the U.S., often including bird-man artifacts intended to empower the soul through a heavenly afterlife. Mounds in the shape of birds were found from Georgia to Iowa and many more were likely destroyed by farming.

Divine birds of Mesoamerica

The rare global phenomenon of three global bird migration flyways converging occurs from the east coast of Mexico across the Yucatan, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama.

The Olmec are considered the ancestral culture of Mesoamerica and their capital La Venta was located where the three bird flyways converge in the Tabasco region of Mexico. A 2,650-year-old ceramic cylinder found at La Venta shows a bird holding a speech scroll with two glyphs that represent what scholars believe was a written language. The glyphs represent a date on the sacred calendar that was ritually celebrated by kings. Also in southeastern Mexico archaeologists recently used LIDAR technology to discover El Mirador, a massive Mayan metropolis estimated to be 3,000 years old.

Just 600 years ago the Aztec believed they were led from their northern homeland of Aztlan (Land of the Herons) by the sun god Huitzilopochtli, also known as the Hummingbird of the Left. Legend has it that Montezuma sent a search party to find Aztlan and when they reached the mountain birthplace of Huitzilopochtli, he turned them into birds for the last leg of the voyage.

Another legend recounts the Aztecs trekking in search of a homeland when a priest had a vision of an island in a lake with an eagle perched on a cactus, devouring a snake. The next day the travelers came upon a lake with an island in the middle where it was said the priest’s vision came true before their eyes. The lake became the city of Tenochtitlán, which is now buried under Mexico City. Today the flag of Mexico depicts an eagle devouring a snake.

To the modern reader it’s impossible to overstate the prevalence of birds in ancient cultures. When the conquistador Hernán Cortés wrote his second letter from New Spain to the Spanish king in 1522, he noted an entire street in Tenochtitlán was set aside for game birds, including “partridges, quails, wild ducks, fly-catchers, widgeons, turtledoves, pigeons, reedbirds, parrots, sparrows, eagles, hawks, owls, and kestrels; they sell likewise the skins of some birds of prey, with their feathers, head, beak, and claws.”

The triple-flyway in Patagonia

In South America, two global bird flyways converge in a relatively narrow southeast-running corridor through the Andes Mountains, encompassing the Old Temple at Chavín de Huántar, Machu Picchu, Lake Titicaca and the city of Cusco, the oldest city in the Americas, founded in 1100.

The oldest cluster of human habitation in the Americas can be found where three bird migration flyways converge in the region of Patagonia, including parts of Chile and Argentina. A 2010 study estimated the hunter-gatherer settlement at Monte Verde in southern Chile is at least 14,500 years old.

In southern Argentina, Patagonia’s Central Plateau shows evidence of rock paintings and flint tools dating back 11,500 years at Casa del Minero, Cueva T˙nel and Cerro Tres Tetas. Human fossils were found at Piedra Museo dating back 11,000 years. Six other sites across Patagonia were settled between 4,700 and 7,700 years ago, likely by the ancestors of the modern Tehuelche Indians.

Combining the bird migration mapping evidence, the location of the oldest indigenous settlements and the widespread belief in birds as seed-bearing creators of the landscape and supernatural ancestral guides makes a plausible case for migratory birds playing a key role in the spread of humanity to the Americas.

Is it a coincidence that the closest genetic ancestors to Native Americans lived in a place, Ust-Kyakhta on the Russian border with Mongolia, where three global flyways converged?

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)