The role of volcanoes in the development of religion has been vastly underestimated in the western world. And scholars continue to debate whether a volcanic event at Mt. Sinai was the true setting for the Old Testament God delivering the 10 Commandments to Moses.

Although every human culture in recorded history practiced some form of religion, scholars can’t simply accept the notion that our distant ancestors, including other human-like species, were also guided by religious feelings. Considering their brains and biology worked the same as ours, it’s safe to assume they also perceived a design to the universe that was both unknowable and greater than themselves.

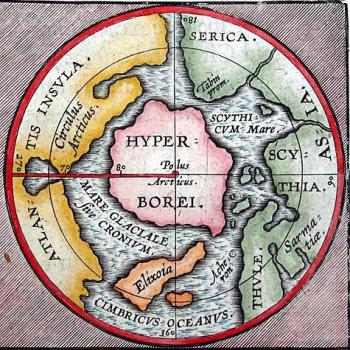

The fossil record shows the earliest bipedal human-like species lived almost exclusively in volcanic areas. Archaeological studies have demonstrated that at least three species of the genus Homo mined magmatic semi-precious stones such as ocher and obsidian over more than a million years.

Located in the volcanic Caucasus Mountains of Armenia, Mount Arteni is the world’s oldest and largest source of obsidian tools and artifacts, dating back 1.4 million years. While the oldest obsidian tools were likely made by Homo erectus, the age of the tools is the only proof. Archaeologists believe Neanderthals and Homo sapiens made most of the obsidian tools at Mount Arteni and they number in the millions, according to archaeologist Boris Gasparyan of Armenia’s National Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology. Mt. Arteni was still in the obsidian business about 3,000 years ago when tools were exported from Armenia to Greece.

The volcanic Imereti region of the Southern Caucasus Mountains in the Republic of Georgia was a prime settlement area for Neanderthals and modern humans, who both produced obsidian artifacts along the snaky tributaries that feed the Kvirli River system. Neanderthals survived in the Imereti region longer than most other parts of Europe, finally going extinct about 27,000 years ago.

The oldest trading network

Almost immediately after emerging on the evolutionary tree, Homo sapiens crafted obsidian tools by an ancient lake in western Kenya about 307,000 years ago, according to a 2018 study. Because the raw obsidian came from a source more than 70 miles away, archaeologists concluded it was the earliest human trade network on record. In 2019, an ancient obsidian mine was discovered in the volcanic Bale Mountains of southern Ethiopia at an altitude of 11,500 feet. The mine operated between 47,000 and 31,000 years ago.

Another obsidian trading network dating back about 50,000 years was identified between eastern Russia and southern China. Geochemical testing showed that obsidian artifacts in Primorye, Russia originated more than 400 miles away near the Paektusan volcano in southern China. Microblade cores were still being produced at the Paektusan volcano just 2,500 years ago. The study also found obsidian artifacts that originated in Primorye, suggesting a two-way trade.

About 5,800 years ago the people of Neolithic Scotland discovered volcanic glass known as pitch stone on the Isle of Arran, which became the source of a sprawling trade network across the British Isles that lasted 400 years, according to a study by the University of Bradford, UK. More than 23,500 pitch stone blades and other artifacts from the Isle of Arran were found at about 350 sites. Obsidian would remain of great value across cultures and through the millennia, all the way to the Aztec and Inca.

Were the trading networks purely a source of useful tools, like a modern day chain of hardware stores? More likely obsidian was perceived as a sacred stone created by beneficent volcano gods to help humans climb up a notch or two on the food chain. Sharp-edged tools were used for everything from cutting and scraping hides to hunting and defending against predators. Anything that improved the chance of survival was considered a sacred gift and our ancestors were thankful to the volcanoes that produced them.

The early 17th century English historian and philosopher Edward Herbert wrote that “nature has implanted in man [a need] to render a due veneration to all those from whom he has received any benefits ….” In The Meaning of Religion (Martinus Nijhoff, 1960), Norwegian theologian William Brede Kristensen wrote that fear is part of the religious experience, “but it is fear containing the mystical element of awe towards that which is inscrutable and sovereign.”

The volcano as mirror of the sun

Scholars agree that ancient cultures perceived another world in the sky that was a mirror of the earth.

In solar religions the volcano was the mirror of the sun, regenerating the earth in a fiery crucible of bright red and orange lava, not unlike the blazing colors of sunset. Half-a-dozen creation stories from Africa, Southeast Asia, Siberia, and North America describe a source of heat suddenly appearing in the middle of a world-covering primordial ocean, resulting in the production of clouds and the appearance of land.

In Chinese myth, an archer shoots down nine suns, presumably to become volcanoes, and leaves the 10th in place. The Zuni of Arizona identified a local volcano as “the son of the sun” who liked to gamble with other nature gods. It’s no accident the Zunis associated games of chance with unpredictable volcanoes.

Prehistoric cultures may not have known the scientific details of volcanoes recharging the soil with minerals and ash layers resisting drought, but they could see well enough that volcanic areas were more fertile than others. They learned that the eruption of deadly red and orange lava set the stage for a vibrant and transformed landscape of blooming vegetation.

Although volcanic eruptions have wiped out human settlements throughout history, volcano mythology doesn’t dwell on terror and destruction but on creation and the passionate feelings of volcano gods. At three archaeological sites from Tanzania to Italy, human-like species left footprints in fresh volcanic ash.

In Laetoli, Tanzania, archaeologists dated footprints in volcanic ash to 3.7 million years ago, made by the bipedal human ancestor Australopithecus afarensis. On the slopes of the Roccamonfina volcano in southern Italy, three Neanderthal teenagers left more than 50 footprints in rain-softened pyroclastic ash and mud about 350,000 years ago. In that case archaeologists say the ash was freshly laid down from a recent eruption.

At White Sands National Park in New Mexico human footprints made between 7,400 and 22,000 years ago (the age is in dispute) were found in brown gypsum soil, which is formed from volcanic vapors and sulfate solution deposited out of lake water. Down through the ages it wasn’t unusual for people to settle in volcanic areas not long after eruptions occurred.

The setting of creation

The eruption of Mt. Mazama in Oregon 7,700 years ago was the largest in the Cascade Range in a million years, and among the largest on Earth in the last 12,000 years.

Not long after the volcanic event created Crater Lake, the Modoc and Klamath tribes moved into the area. A Modoc creation story describes the Chief of the Sky Spirits descending to a volcano where he built a lodge and created rivers, animals, fish and birds. The smoke from the chief’s hearth rose through a hole in the roof and when he dropped a big log on the fire, sparks flew up through the hole and the ground trembled. The chief put out the fire and returned to the sky.

In Indonesia the Javanese have long believed that rulers of the spirit kingdom live inside the volcanic Mount Merapi (Fire Mountain) in a paradise where virtuous ancestors spend the afterlife, complete with roads, vehicles, and domesticated animals. Starting on October 25, 2010, pyroclastic flows from a major eruption killed 353 people and caused 350,000 residents to flee their homes.

A mythic story equating volcanoes with the passion of human hearts comes from the Koryak of Siberia, who say a Great Raven created men to love women passionately so the tribe would continue. The men were buried in a sacred place where their passionate hearts, burning with love, grew into a volcano. Other myths describe passionate volcano gods caught in love triangles and driven by passion, totally oblivious to humans who might live in the area. In Mesoamerica, the Aztecs believed that Popocatepetl (the Smoking Mountain) and Iztaccihuatl (the White Lady) were lovers who could not bear to be out of each other’s sight, and occasionally sent fiery missiles in each other’s direction. Hawaiian chants tell the story of an explosive and vengeful love triangle among local volcanoes.

A human heart again plays a role in perhaps the spookiest volcano legend ever told: When the Toltec of Mexico were in decline, and erupting volcanoes were visible from the capital city of Tollan, the people gathered for a human sacrifice. The crowd was used to observing such rituals and followed the tradition of cutting themselves at the same time to give energy to the gods. But this time they recoiled in shock and horror when the priest cut open the sacrificial victim’s chest only to find he had no heart. This was the mythic end of the Toltec.

The blood of immortal gods

Although bright red ocher has been the most widely used pigments in human history, the source of its symbolic value remains mysterious. The most common rock containing red ocher pigment is hematitite, an iron-rich semi-precious stone that forms through magmatism and has the same physical appearance as obsidian.

The symbolic power of red ocher may have been linked with red lava, the blood of the volcano god, and the awesome regenerative power of the earth. At Olorgesailie in Kenya, two pieces of ocher-rich rock were recently found to be “intentionally shaped” by early humans at about the same time the first obsidian trading network emerged in the region more than 300,000 years ago, according to George Washington University paleoanthropologist Alison Brooks, who identified the twin developments as “a radical shift in behavior.”

Perhaps the use of red ocher in burials represented the fiery, passionate and immortal blood of volcano gods intended to regenerate the souls of mortal beings. Archaeologists believe ocher may have played a role in the emergence of abstract thinking.

Overlooking the ocean on the coast of South Africa is Blombos Cave, where an early human used ocher to draw red crosshatching lines about 73,000 years ago. The grid has been identified as the oldest abstract drawing ever found, according to the University of Bergen in Norway. Much later examples of the crosshatch pattern from Neolithic Europe to Native Americans is thought to represent snakeskin, a symbol of regeneration. Some of South Africa’s deadliest snakes live along the coast, including the Cape cobra, black mamba and puff adder.

Like a painter’s palette, the spiral shells of sea snails were used at Blombos Cave to store a paint-like liquid form of red ocher mixed with ground bone and charcoal. In later cultures the spiral was also a symbol of regeneration.

The animism concept

The age-old concept of animism meant that a “spiritual character” was projected onto natural phenomena that possessed “a self-subsistent energy upon which man is dependent … and by which he finds his life determined.” according to The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study of Human Nature (Longmans, Green & Co., 1902), by Harvard University psychologist and philosopher William James.

The French social scientist Émile Durkheim wrote that myths describe a “power or influence … in a way supernatural (that) manifests itself in physical form.” The German scholar Max Muller and German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher also believed that humanity’s relationship to self-subsistent natural phenomena was the essence of religion. French author Bernard Le Bovier, sieur de Fontenelle, wrote that myths are an attempt to explain unknown sources of power. Dutch philosopher Gerard van der Leeuw wrote that “it is neither nature nor natural phenomena as such that are ever worshipped but always the Power within or behind.”

In the underrated cult movie Joe Versus the Volcano, a delirious Tom Hanks is on a raft in the Pacific Ocean watching a giant moon rising on the horizon. “Dear god whose name I do not know. Thank you for my life. I forgot how big … Thank you, thank you for my life.”

Commandments etched in blue sapphire

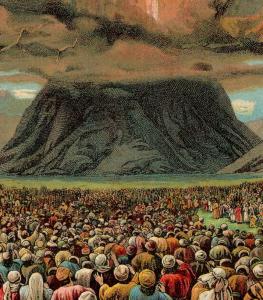

The Israelites arrived at Mt. Sinai three months after escaping Egypt, setting the stage for one of the most well-known stories in history. As Moses gathered the people, God shook the ground and covered Mt. Sinai in a cloud. Scholars continue to debate whether the events at Mt. Sinai were volcanic in nature.

“There were peals of thunders and flashes of lightning, dense cloud on the mountain and a loud trumpet blast; the people in the camp were all terrified.” Traditionally interpreted as a violent thunderstorm, some Biblical scholars point to the absence of wind and rain in the text to suggest God’s appearance coincided with a volcanic event, which often generates thunder and lightning around the top of a volcano.

The Talmud and Mishna say the Ten Commandments were etched in blue sapphire, almost as hard to cut as a diamond: The use of sapphire must have been strictly metaphysical. The choice makes more sense when considering sapphire is created by volcanic activity.

Meanwhile scholars agree that Mt. Sinai and Mt. Horeb were two names used for the same mountain, and Horeb translates as “glowing heat.” With Mt. Sinai covered in clouds and lightning, the description of onlookers as “terrified” suggests something more than a thunderstorm. People were pretty tough in those days and weren’t likely to be terrified by bad weather.

But as God recited the Ten Commandments the people “trembled and stood at a distance.” A distance from what? Imminent pyroclastic flows? Moses explained that God made the frightening display “so that the fear of Him may remain with you and keep you from sin.”

A powerful thunderstorm seems unlikely to cause the average person to upgrade their moral character, but surviving a volcanic event might do the trick. Leading the Israelite’s trek through the desert, God appeared as a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. Clouds don’t often appear in the form of a pillar unless they’re shooting out of a volcano. Same for pillars of fire. And God dispatched the Egyptian army by using pillars of fire and cloud at once.

“…the Lord looked unto the host of the Egyptians through the pillar of fire and of the cloud, and troubled the host of Egyptians, and took off their chariot wheels …” A pyroclastic flow would surely incinerate an army’s chariot wheels.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: an eco-history of myth and religion, released April 2023 by Moon Books and John Hunt Publishing. Order here or at other booksellers. More information can be found at this website, which links to a pair of YouTube videos written by the author and produced by JHP.)