Reenacting the moment of creation inside the body and mind has long been a cross-cultural shamanic practice.

The majority of creation myths begin with a source of heat evaporating dormant waters into the first clouds and storms – the birth of weather and the perpetual water cycle (see previous column for more on this). Across numerous cultures, shamanic figures have recreated the moment of creation internally by generating a spiritual heat that produces a divine vapor, empowering the shaman to travel in the spirit world and heal the sick.

Ancient origins

In the genetic cradle of humanity, the San tribe of the Kalahari Desert in Southern Africa is protected by law, including weekly communal dances lasting all night that produce a state of healing trance that’s been described as like death or flying, but at the same time, “make(s) the heart happy.”

The San shaman call themselves Masters of N/um, a spiritual form of water in the stomach that’s heated by dancing and turns to spiritual vapor that rises up the spine to the head. When n/um reaches the mind, the San healer can fly as a spirit, see over enormous distances and diagnose illness.

The San shaman wipes his n/um-infused sweat and works it into the body of the sick as other healers wipe their sweat on the shaman. One healer said, “When I make the n/um rise, it explodes and tosses me up into the air; I enter heaven and finally fall back down again.”

“The blossoming of the silver flower” is a similar practice from ancient Taoism, which describes a fiery energy that heats a bowl of spiritual water in the lower tan-t’ien (above the hips), producing a rising vapor of regenerative energy. The metaphysical bowl of water is yin and the rising steam is yang.

The Fox tribe of the Great Plains identified steam as manitou, the essence of the supreme being that was present in all things. In the sweat lodge manitou emesrge in the steam and circulates throughout the body, driving out pain and leaving behind a feeling of spiritual wellness.

A Wichita legend describes a miraculous scene when a father poured water over the fire in his lodge and the steam that enveloped his family turned them into eagles that flew to the heavens. In a similar vein, the apprentice shaman of the Shuswap in British Columbia would build a sweat-house where he would dance and sing until his helping spirit appeared, often in the form of a bird.

Cleopatra dabbles in alchemy

Cleopatra was deeply interested in alchemy, including a ceramic vessel in the form of a woman’s body that reproduced the process of evaporation and condensation. The vessel was said to be invented by Maria Prophetissa, the legendary sister of Moses.

Heated water in the lower portion of the vessel produced vapor that rose and condensed into droplets on the breasts that formed the upper portion of the vessel, representing the milk of a goddess. It was “… a vessel within which all the macro-cosmic processes are caught and at the same time grasped and conceived.” The repeated evaporation, condensation and precipitation of divine water was believed to create an elixir of life for souls of the dead.

In a Hellenic text based on Egyptian sources, Cleopatra said divine water caused the dead to “sprout out of the underworld and come up and clothe themselves in beautiful colors like the flowers in spring … ” Further details can be found in Marie-Louise Von Franz’ Creation Myths, Revised Edition (Shambhala, 1995).

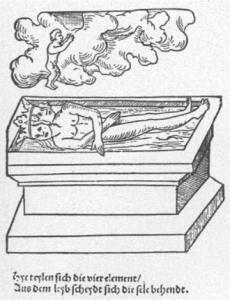

Reviving the dead

In the 16th century Rosarium Philosophorum, German alchemists describe experiments intended to achieve immortality through a new method of human cremation featuring the evaporation and condensation of water. The heat from cremation produced vapor from a vessel of water. The steam rose and condensed back into liquid that was returned through the process repeatedly. With every round of “sublimation” the water was further purified. The ultimate purpose of the ritual was to re-seed the soul by sprinkling purified water on the cremated ashes. The concept was to cleanse and heal the soul but also to impregnate and transform it. “The divine water is … the reducer of the soul into his body, which revives after his death … ”

The Rosarium used Christian phraseology to describe water as the genesis of all things: “Of water all things are made and the spirit of the Lord was carried on the water, and the beginning of the generation of man was of water.”

The universality of saunas

With the notable exception of post-Classical western culture, just about every race, tribe, religion and ethnic group throughout history and pre-history has considered steam an essential part of physical and spiritual health.

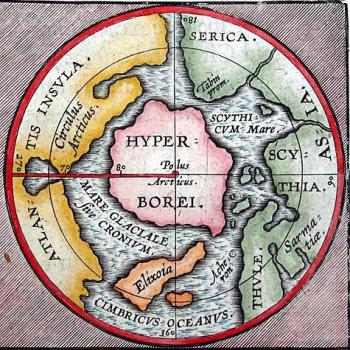

Saunas were part of the medical, spiritual and social fabric of life in ancient cultures from Scandinavia to Egypt and Greece, Eastern Europe, India, Southeast Asia, Russia, China, Korea and Japan. When the Scythians arrived at the Black Sea about 2,600 years ago, the Greek writer Herodotus observed them taking steam-baths and burning hemp seed.

Archaeologists have recently discovered what they believe were Neolithic-era stone saunas in Scotland, Finland, Greenland and Newfoundland. The compelling evidence at each site was a massive pile of badly scorched stones in a fire pit.

It should be no surprise that saunas were used in ancient Finland, where virtually every baby was born in a sauna before the advent of modern medicine. In Finland, Hungary and Latvia the word for steam or vapor also means spirit or life. Indigenous cultures in Laos and Thailand and throughout the Americas have used or continue to use the sweat lodge for giving birth and post-partum healing.

Was Brú na Bóinne a sauna?

There’s compelling evidence that Neolithic-era steam rituals were held inside megalithic structures that were explicitly aligned to the dawning sun on the winter solstice, the pagan birthday of the sun. Heat and water equals steam.

All the elements of a sauna are present in County Meath, Ireland, where the megalithic mound known as Brú na Bóinne dates back 5,200 years, featuring a 60-foot passage that carries winter solstice sunbeams into the central chamber, where three large granite bowls still sit.

To create a sauna in the central chamber, it would have been easy enough to seal the small opening atop the dome with a flat stone, place heated quartz in the three granite bowls and bring in water from a year-round spring that once surfaced inside the 60-foot passage. (The spring has been capped.)

Although the builders of Brú na Bóinne took great pains to divert water from the central chamber, which remains dry today, they left a dripping leak that once filled the large granite basin in the east recess during the winter. The slow-dripping leak was first documented in 1699 and officially plugged by archaeologist Michael J. O’Kelly, who rehabilitated the site in the 1970s.

Perhaps in the pre-dawn hours of the winter solstice, druid priests used antlers to bring hot quartz into the pitch-dark central chamber, placed the glowing rocks in the east basin and waited for the dripping snow-melt to hiss onto the stones, filling the chamber with steam.

When the sun entered the chamber it would have illuminated the coiling steam in a dramatic re-enactment of the moment of creation, when vapors gathered into clouds. Clear quartz stones could have been used to refract the colors of the rainbow through the steam.

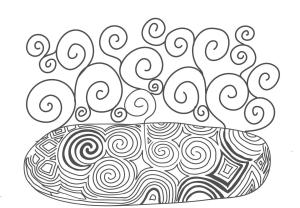

Interpreting the Entrance Stone

Scholars continue to label Brú na Bóinne a passage tomb and numerous books have suggested a wide array of esoteric pagan rituals that may have occurred there. Despite the mound’s suggestive design no one has thus far proposed that Brú na Bóinne was a sauna. Meanwhile the massive Entrance Stone could be interpreted as an ancient sign indicating just that.

The deeply carved lines show diamond-shapes with lines radiating outwards, perhaps symbolizing heat radiating from quartz. The radiating lines morph into spirals, possibly representing clouds of steam. A triple spiral (triskelion) etched in stone just above the basin in the back recess of the central chamber may represent steam rising from the basin.

Irish legend describes three princes who came to Brú na Bóinne to learn the wisdom of kings, a process that included fasting for three days in the darkness of the central chamber. Adding steam to the experience of fasting and sensory deprivation would have been consistent with the spiritual practices of dozens of other cultures.

A place of birth, not death

Cultural evidence suggests Brú na Bóinne didn’t just celebrate the rebirth of the sun each year, but the actual birth of people and animals.

A 10th century Irish text known as The Dindsenchas identifies Brú na Bóinne as the home where the Dagda slept with his wife, along with two smaller mounds with chambers just to the west, “where Cermait was born, behold it there, not a far step.”

Another text refers to Brú na Bóinne as a place where the finest hounds were bred. In the Neolithic era the salmon that spawned in Boyne River by the mounds were far bigger than they are today. And of course the enormous mound was painstakingly aligned to the birthday of the sun.

Yet Brú na Bóinne is still officially considered a passage tomb, a label applied by Christian scholars to a monument erected by people with profoundly different beliefs about the meaning of death. Certainly the ancient Irish tribe known as the Tuatha De Danann, who created a mythic cosmology around the Boyne Valley, believed in reincarnation.

A member of the Danann named Tuan MacCarell was said to pull a fast one during Noah’s Flood, reincarnating as a salmon for a spell before living dozens of human lifetimes and eventually relating Irish history to St. Patrick.

Further evidence of steam rituals at temples aligned to the winter solstice can be found at the Sun Temple at Konârak in India, where the floor of the inner sanctum slopes to the north towards a drain, suggesting water was used during rituals. The inner sanctums of ancient Egyptian temples — including the solstice-aligned Temple at Karnak — were described as “the genuine great sea of the first occasion,” referring to the primordial sea of Nun. Also typically present in the Egyptian inner sanctum was a representation of the pyramidal (crystalline) Benben stone, which fell into the sea of Nun at creation.

In Egyptian creation myth the Bennu bird represented the first cloud as a grey heron atop a pillar, calling out for the first time.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)