Given all the attention that Islam and Muslims get today and all anxiety that exists over their relationship to America, I’m often surprised how little attention is paid to the American Muslims as a community and subculture.

For all the provincialism and resentment that reigns in many quarters towards America’s increasing ethnic and religious diversity, I think it’s fair to say that Muslims are set apart these days by the extent to which they are widely assumed to be intrinsically *foreign*. There are obviously benighted yokels and bigots who find Latinos, Asians, or Jews, or Catholics, …, self-evidently less “American” than whites, but their twisted categories rarely jump species into mainstream politics or polite company.

Not so, I’d argue, with Muslims these days. Many people–including some well-meaning people–arbitrarily exclude Muslims from the fold at the same time that they hold up the inclusivity and malleability of American identity as a model for the rest of the world.

So it’s a pleasure to see the current cover story in The Christian Science Monitor (“Islam, the American Way”, 2/16/2014) by Lee Lawrence on the new religious identities that are emerging among American Muslims.

It’s thougtful piece. I particularly like how it provides a taste of the significant theological and ideological diversity that exists among American Muslims. It’s a commonplace that Muslims run the gamut from liberal to conservative. Far more interesting and valuable, though, is the insight that such categories are quite inadequate for predicting people’s individual beliefs, practices and inclinations.

An economist at the US Department of Agriculture, Ali, too, has had surprises since moving to the East Coast. At a professional gathering with fellow Muslims, she was taken aback when bearded men – her signal for conservative – extended their hand to shake hers. Or when, on Facebook, she noticed women who cover – hijabis – supporting same-sex marriage. She’d unconsciously assumed fellow hijabis would share her belief that homosexuality is a sin. Instead, she reports that some say, “No, I don’t think it’s a big deal; I think it should be legalized.”

One of the scholars the piece quotes is Shabana Mir, who happens to be my wife. Which is is an added bonus as far as I’m concerned.

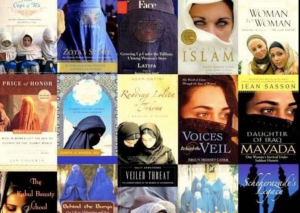

While I’m at it, I should put in a hearty plug for her recent book, Muslim American Women on Campus: Undergraduate Social Life and Identity, on the intersection of Muslim American religious identity and gender norms.

I think the book is a useful corrective to the manner Muslim women are often portrayed in the MSM as voiceless pawns in the struggle between religion and modernity. On the one hand, it gives you a sense of the pressures that young Muslim women sometimes face–often from both camps at the same time–as they negotiate religious life and American culture. (And the way that the fundamental, non-negotiable categories imposed by each camp are not infrequently myopic and/or mutually exclusive is captured in interesting vignettes.) On the other, it highlights examples of the sophisticated balancing act that many Muslim women perform as they move between communities on campus and balance their personal commitments, forging new paradigms of both Americanness and piety that make sense in their world.

The issue that interested me most was perhaps what one might call the psychological gravitational pull of booze and dating in campus life even when you do not participate in them, the way one finds oneself defined in relation to particular practices regardless of whether or not one participates in that activity. For example, even if one does not drink, it is much easier said than done to truly opt out of the extended culture of drinking. In some respects, my situation was perhaps simpler than that of these women but I remember one thing well from my own teetotal-ling undergrad days in the early 1990s. I didn’t want to drink, completely rejected the idea that there was anything weird about not drinking and was very conscious of how booze often ruins social gatherings, but that didn’t remove the sense in the back of my mind that I was a little less cool on some level for it. Regardless of how one feels about the prevailing norms–whether one partakes of the new-found freedoms of campus life or abstains–one does not escape the social and psychological categories that accompany them. They still affect you. And then there is how much deviance one’s peer group or internalized norms allow. Some kinds of deviance are seen as a normal aspect of personal tastes, whereas other types of deviance damage one’s social standing and must be managed, perhaps by compensating with zealous conformity in another area (e.g., the non-drinker who avoids seeming “square” by otherwise being the life of the party).

It’s a complex, fluid situation which leads to all sorts of interesting moves and choices–concessions, compensation, resistance, reappropriation, cooptation–by these young women as they perform their “identity work” in everyday life.

If such issues interest you, you might enjoy her book.