Throughout the Bible, and in the teachings of Jesus in particular, rarely do we find specific directives on political policies, platforms, and parties. Instead, Jesus and the Bible as a whole seek to expand our imaginations, to transform our minds, so that we can test and approve God’s will, that which is good, pleasing, and perfect, in our own time and place. While the responsibility falls on us to discern how to seek the peace and welfare of our society, the Bible utilizes historical examples, and Jesus utilizes parables, to expand our imagination about how to live as faithful citizens.

Others have likewise provided stories to spur our imaginations about how to create a just and equitable society.

The political philosopher John Rawls argues that a just society is a society that is fair. In order to imagine such a society, Rawls asks us to imagine a group of citizens determining how their society should be structured.

But Rawls provides a twist: each citizen at the table is ignorant of what their place will be in the society. They don’t know what their race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, wealth, natural endowments, and so on will be within this society. In other words, they don’t know whether they will end up as the privileged or underprivileged member of the society.

Rawls believes that such people would create the most just and fair society in order to ensure that, whether they’re on the top or the bottom of the society, they’ll be able to have a good life.

The problem with this thought experiment is that it’s simply impossible for us to bracket our own biases and privileges as citizens. As much as we might like to think it’s possible for us to be fair and unbiased, we aren’t colorblind or ignorant to class, age, and gender differences. So while Rawls’s thought experiment may provide an ideal for justice and fairness, it is difficult to imagine how it could work in practice.

Nearly 125 years ago, the social gospel minister Charles Sheldon provided another thought experiment with his novel In His Steps, one of the best-selling books of all time.

In the novel, Sheldon imagines the residents of a fictional town of Raymond asking themselves “What would Jesus do?” as they make decisions for their town. As the novel progresses, this guiding question, “What would Jesus do?” spreads to the much larger city of Chicago, and individual’s lives and society at large are transformed by following in the steps of Jesus.

This thought experiment caught the attention of many Christians, as “What would Jesus do?” (or WWJD?) became a fad. In the early 2000s, it was common to see Christians, and even celebrities, sporting colorful WWJD? bracelets.

The problem with this thought experiment is that few people actually stopped to determine what Jesus did do in his time and place and how that relates to their decisions in their time and place. By and large, people just assumed that Jesus would have done pretty much whatever they were already doing. And so WWJD? simply gave Christians a divine seal of approval on their own actions and decisions, political or otherwise.

In Jesus’s teaching of the teaching of the sheep and the goats, Jesus offers us another thought experiment altogether. Instead of trying to imagine we’re colorblind and ignorant of privilege, as with Rawls, or imagining we’re in the place of Jesus, as with Sheldon, Jesus allows us to remain who we are. The responsibility is on us, whoever we are and whatever our privileges in society may be, to determine how we are going to act in society.

But the twist in Jesus’s story is this: we are to imagine that Jesus is found among the least of those in society, among those who are oppressed or underprivileged. Jesus asks us to consider not so much the question “What would Jesus do?” as the question “What would you do for Jesus?”

If you learned that Jesus was among those facing food insecurity, what would you do?

If you learned that Jesus was among the homeless population, or among those seeking refuge or asylum from another land, what would you do?

If you learned that Jesus was among those lacking adequate clothes for the winter, what would you do?

If you learned that Jesus was among those with chronic illness, or among those especially vulnerable to COVID-19, what would you do?

If you learned that Jesus was among those incarcerated at the county jail, or state or federal prison, or immigration detention center, what would you do?

This isn’t a mere hypothetical, as Jesus says that we will be judged by how we answer it, and especially by how we act on our answer.

Some read Jesus’s teaching here fairly narrowly as speaking strictly to acts of charity or hospitality and not to political engagement or advocacy for social justice. And it’s true that the examples Jesus gives are interpersonal: providing food, drink, and clothing; inviting one into your home; and visiting those who are sick and in prison.

Those specific examples are plenty challenging in and of themselves. While we may distribute food, drink, and clothing to those in need through a church pantry, and may at times visit a friend, relative, or neighbor in the hospital or jail, many of us would find it difficult to invite a stranger into our home (even leaving aside social distancing guidelines).

But Jesus makes it clear that he isn’t limiting his parable to these specific instances of charity or hospitality. Instead, he is trying to expand our imagination to consider the marginalized and oppressed as bearing Jesus’s presence in the world.

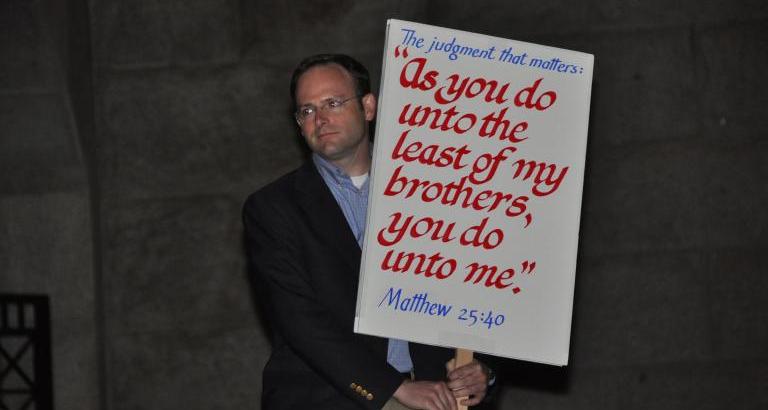

He thus has the king say, “I tell you the truth, when you did it to one of the least of these my brothers and sisters, you were doing it to me!” And, “I tell you the truth, when you refused to help the least of these my brothers and sisters, you were refusing to help me.”

The New International Version translates this, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” And, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.”

The New King James Version translates it, “Assuredly, I say to you, inasmuch as you did it to one of the least of these My brethren, you did it to Me.” And, “Assuredly, I say to you, inasmuch as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to Me.”

As these different translations suggest, the point isn’t about prescribing specific action steps. Instead, it’s about viewing any and all acts of love toward neighbor as acts of love toward Jesus. And, conversely, it’s about viewing any and all refusals to love neighbors with concrete acts as refusal to love Jesus concretely.

This is what it means to be a faithful citizen today: to see Jesus in the face of those who are marginalized, oppressed, or denied justice and to act accordingly.

This is how we see the world when God transforms our minds to change the way we think: we see a world infused by the presence of Christ in the face of our neighbor.

This is how we learn to know what God’s will is for us: not by trying to discern some esoteric biblical code or subtle signs from the Spirit, but by asking each other, “What would you do for Jesus?”

This is how we test and approve, in our own time and place, that which is good, please, and perfect.

This is how we practice faithful citizenship.