Junia: Outstanding Apostle

By Drew Strait

Read Romans 16:1–7; Acts 2:14–21

In her TED talk, titled, “The Danger of a Single Story,” the Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about the power of story and literature to shape how we think about our lives. She recalls growing up in Nigeria reading British novels with blonde haired, blue eyed children who drank ginger beer. When Adichie started writing her first stories as a child, she found herself writing exclusively about blond haired, blue eyed children and ginger beer despite the fact that she had never tasted ginger beer and her family and friends were all black.

It wasn’t until Adichie was introduced to African literature that she realized that girls that look like her can also exist in literature. Adichie reminds us just how impressionable and vulnerable we are in the face of a single story, and how humans throughout history have created a single story to stigmatize and oppress people and thereby lord their power over them. Here, at the intersection of story and power, Adichie is worth quoting in full. She says,

Show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become. It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power. There is a word, an Igbo word, that I think about whenever I think about the power structures of the world, and it is “nkali.” It’s a noun that loosely translates to “to be greater than another.” Like our economic and political worlds, stories too are defined by the principle of nkali: How they are told, who tells them, when they’re told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power. Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. . . . Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story. . . . The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.

Friends, I’d like to propose this morning that many of us—perhaps even most of us—have been told a single story about women in the early church that is incomplete.

Growing up in the church, I was taught to think that Jesus had twelve male apostles. I remember learning about Peter, James, and John. I remember learning about Andrew, Philip, Bartholomew, Matthew, and Thomas. I remember hearing about James, son of Alphaeus; Simon, the so-called Zealot; Judas, son of James; and, of course, Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus. I remember learning about Matthias, who replaced Judas Iscariot, and I especially remember learning about Paul, who converted to the way of Jesus after persecuting Christians and became an apostle to the gentiles.

But I have no memory of any pastor, teacher, mentor, or youth group leader teaching me that there was also a female apostle in the early church. In the circles that I grew up in, manhood was a prerequisite for apostleship, and women were largely relegated to the periphery of church leadership.

In teaching us a single story about women, the church created a hierarchy of power.

In teaching us a single story about apostleship, Bible teachers created a gendered caste system.

In teaching us a single story about who can proclaim the gospel with authority, church leaders undermined the church’s full witness to a justice-making, liberating, forgiving, and fiercely faithful God.

Friends, I’m so happy to let you know this morning that this single story we were taught is not the full story—in fact, it is not the whole gospel.

Here I want my own voice to get out of the way and allow Paul to speak.

In Romans 16:7, Paul writes:

“Greet Andronicus and Junia, my Jewish relatives who were incarcerated together with me; they are outstanding among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was” (translation mine).

In the male-dominated world of biblical interpretation, the presence of a female apostle caused many men to squirm in their seats. In fact, the presence of Junia made some male biblical interpreters like Martin Luther so uncomfortable that they literally man-washed her out of the story and changed her name from Junia to Junias—a him instead of a her.

What’s striking about the man-washing of Junia is that we have no literary or material evidence of anyone in the Roman world with the male name Junias. However, we have over 250 examples of women named Junia.

Even so, some major English translations of the Bible popularized the masculine reading. Hear, for example, the Revised Standard Version—a translation that some of you may have grown up reading:

“Greet Androni′cus and Ju′nias, my kinsmen and my fellow prisoners; they are men of note among the apostles, and they were in Christ before me.”

Here not only is Junia man-washed with the masculine Junias—but the translators also add that “they are men of note among the apostles,” despite the fact that the word men does not occur in the original Greek! Indeed, as one commentator writes, “Junias is a figment of a chauvinistic imagination.”

In more recent years, conservative male biblical interpreters have mostly conceded that Junia was a woman since we have no evidence of someone named Junias existing in the ancient world. Yet the thought of a woman being an apostle remains so uncomfortable for these men that they’ve sought other ways to man-wash Junia’s apostleship.

For example, in 2001, two conservative male biblical scholars argued that the phrase “outstanding among the apostles” (syntactically speaking) should be translated as “esteemed by the apostles.”

Do you see what they did there? To maintain patriarchal views of apostleship, these authors suggest that Andronicus and Junia are simply “esteemed by the apostles” rather than outstanding apostles themselves!

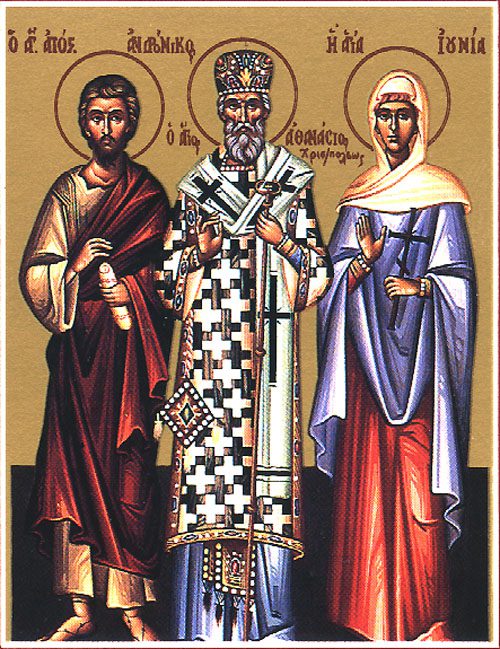

The lengths men have gone to man-wash Junia are especially striking given the fact that no less than eight early interpreters understood Junia as a woman and an apostle. For example, in the fourth century, church father Chrysostom wrote this:

It was the greatest of honors to be counted a fellow prisoner of Paul’s. . . . Think what great praise it was to be considered of note among the apostles. These two were of note because of their works and achievements. Think how great the devotion of this woman Junia must have been, that she should be worthy to be called an apostle! But even here Paul does not stop his praise, for they were Christians before he was. (Homilies on Romans 31, Trans. ACCS, 372)

And in the fifth century, Theodoret of Cyrrhus wrote this about Andronicus and Junia:

Yet more praises. These people were companions of Paul in his sufferings and even shared imprisonment with him. Hence he says that they are men and women of note, not among the pupils but among the teachers, and not among the ordinary teachers but among the apostles. He even praises them for having been Christians before him. (Interpretation of the Letter to the Romans, Trans. ACCS, 372).

In naming Junia outstanding among the apostles, Paul reminds the church at Rome that women are liberated from patriarchal or male-dominated structures.

In naming Junia outstanding among the apostles, Paul reminds the church at Rome that women are emissaries sent out into the world to bear witness to the kingdom of God in word and deed.

In naming Junia as a fellow prisoner, Paul reminds us that the early church was led by fiercely faithful women who agitated the values of the empire.

In naming Junia as being “in Christ before me,” Paul animates Junia’s apostleship and his own mantra that he was the last and least of all the apostles (1 Cor. 15:8–9; Gal. 1:17).

Friends, there has been a gravitational pull throughout church history to man-wash women out of leadership in ministry—to tell a single story. But a man-washed church is not a whole church, nor is it the whole story.

At Keller Park Church we strive to be a protest movement that defies and resists such patriarchal gravity. We protest patriarchy not because we are all liberal or Democrat or feminist but, rather, because we believe that, in Jesus, God has liberated women to lead, flourish, and become sent ones into our communities on behalf of God’s kingdom.

This is what we see in the fiercely faithful Junia, a Jewish-Christian woman who preceded Paul himself in the faith, who, like Paul, was imprisoned for her faith, and who, like Paul, was considered an outstanding apostle by the early church.

It is no accident that when the church’s mission was birthed at Pentecost and empowered by the Holy Spirit, that the apostle Peter reads from the prophet Joel. Hear these ancient words:

“In the last days it will be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy.”

Go and do likewise. Amen.