I think of my great-grandfather when I think of Frederick Douglass.

I’m told that my great-grandfather, born into slavery in 1862, never learned to read or write. But he insisted, when his youngest son married a woman who could read and write, that she would become the teacher for all of the children in the family, and he built a schoolhouse on his land to provide a school where none was provided. The words, “Until we’re educated, we’ll always be somebody’s slaves,” were attributed to him.

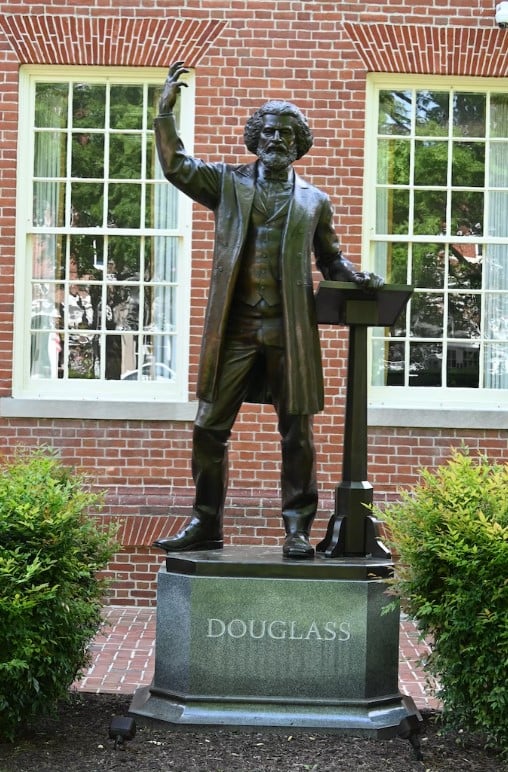

Apparently, my great-grandfather and Frederick Douglass held that belief in common. Douglass, born into slavery in 1817 or 1818, realized as a young child that there must be something quite important about being able to read and write – important enough that his slaveowner insisted that enslaved persons should learn to neither read nor write. Douglass reasoned from that insistence that education must be an important means to freedom, and he worked diligently to teach himself those tools that were not otherwise available to be taught to him.

The skills proved valuable for Douglass. He was only about 27 years of age in 1845 when he wrote the first of his books, an autobiography entitled Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. The narrative of his years as an enslaved person was so well-written, in fact, that it spawned doubt that he was actually its author. But his gifts and skill as an orator keen upon telling his story and arguing for the abolition movement swayed the public. Douglass had escaped from slavery in Maryland, making his way to New York in 1838, where he there declared himself free. Fearing capture and return to his slave owner in Maryland, Douglass moved on to Massachusetts. He engaged in various manual labor jobs, as he discovered his gifts as a speaker, and worked as a tireless advocate for abolition. Knowing that he would forever be in danger of being captured and returned to his slaveowners, he traveled to and spoke in Ireland and Great Britain after penning his book. He grew in relationship with abolitionists who purchased his freedom, and he returned to the United States.

Douglass’ writing and oration skills continued to serve him well. He continued his work with American abolitionists, published a newspaper, and advocated for education and school desegregation. He endured beatings, yet remained undeterred. As the Civil War began, he recruited black men to serve in the Union Army. He would go on to write two more books, publish his newspaper and speak at any number of occasions, perhaps one of the most famous being his July 5, 1852 address in Rochester, on “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro,” from which the following is taken:

For the present, it is enough to affirm the equal manhood of the Negro race. Is it not astonishing that, while we are ploughing, planting, and reaping, using all kinds of mechanical tools, erecting houses, constructing bridges, building ships, working in metals of brass, iron, copper, silver and gold; that, while we are reading, writing and ciphering, acting as clerks, merchants and secretaries, having among us lawyers, doctors, ministers, poets, authors, editors, orators and teachers; that, while we are engaged in all manner of enterprises common to other men, digging gold in California, capturing the whale in the Pacific, feeding sheep and cattle on the hill-side, living, moving, acting, thinking, planning, living in families as husbands, wives and children, and, above all, confessing and worshipping the Christian’s God, and looking hopefully for life and immortality beyond the grave, we are called upon to prove that we are men! Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? that he is the rightful owner of his own body? You have already declared it. Must I argue the wrongfulness of slavery?

Douglass persevered in the struggle for freedom for enslaved persons.

Douglass appears to be among the first black men documented to visit a sitting President at the White House. Jon Meacham chronicles in his book, And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle (2022), that Douglass visited Lincoln at least three times at the White House. On his first visit, in August 1863, he advocated for fair wages for black Union soldiers. He returned shortly after, and Lincoln sought his counsel about whether anything short of a total abolition of slavery could ever be negotiated between the Union and Confederacy. Following President Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration in March 1865, Douglass visited Lincoln to pay his respects at what would be his last visit with Lincoln. Apparently, police officers at the White House refused to admit Douglass, telling him no black persons could enter. But after Douglass insisted that the President be told that he was there, he was allowed to enter. Lincoln greeted him warmly, as he had always done, giving Douglass hope that perhaps, in spite of the way he had been treated by the officers, black persons could experience a long-hoped-for freedom.

Certainly, the end of the Civil War on April 2, 1865, was more cause for hope for Douglass. Although Lincoln had publicly stated in 1858 that he was not in favor of granting the vote to black persons, his point of view changed over the course of the war as he watched black soldiers fighting for the Union. Meacham’s book notes that Douglass understood Lincoln’s measured approach to freedom and granting rights.

The President’s untimely death did not dissuade Douglass. After Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, Douglass continued to advocate for freedom and for Reconstruction. The Atlantic – a magazine that touts itself as having been “founded, in part, to argue in favor of abolition”, included a powerful work by Douglass arguing in favor of Reconstruction in 1866, and in favor of granting suffrage to black men in 1867. The Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution – the 13th (ending slavery and granting freedom to all enslaved persons), 14th (granting citizenship to the newly freed slaves and extending equal protection and due process under the law) and 15th (granting the right to vote to black men) Amendments – were ratified in 1865, 1868, and 1870, respectively.

Following the death of his wife of 44 years, Anna Douglass, he was remarried in Washington D.C. to Helen Pitts – a white woman – in 1884. Their marriage would surely have been among the earliest legal marriages between a black person and a white person in the United States and was reportedly very controversial. Several years of their married life were spent outside of the country.

Douglass died following a heart attack on February 20, 1895, as he was preparing to make yet another speech. His words had resounded throughout a nation. I’d like to think that perhaps Douglass’ words made their way all the way down to a farm in rural south Alabama, to my great grandfather, a man who dreamed big dreams for his own family and stood taller because Frederick Douglass had given him hope.

Many Christian churches celebrate Frederick Douglass each year on February 20, the anniversary of his death in 1895. The Episcopal Church offers this prayer in commemoration of and in thanksgiving for his life:

Almighty God, whose truth makes us free: We bless your Name for the witness of Frederick Douglass, whose impassioned and reasonable speech moved the hearts of a president and a people to a deeper obedience to Christ. Strengthen us also to be outspoken on behalf of those in captivity and tribulation, continuing in the Word of Jesus Christ our Liberator; who with you and the Holy Spirit dwells in glory everlasting. Amen.