In 2017, I stumbled across an article about a statue of a physician named J. Marion Sims, who had lived and practiced medicine in Alabama and New York in the mid-19th century. Dr. Sims has been recognized as the “father of modern gynecology,” credited with having developed the speculum and other instruments now commonly used in the care of women. Sims was also credited with the pioneering the surgical repair of the vesicovaginal fistula, a condition in which a delivering mother’s bladder is injured, leaving her with permanent incontinence and perhaps even more severe complications. The value of Sims’ contributions to the science of gynecology should not be understated, nor should the ways in which his work has continued to improve the lives of women even today.

What has been debated more recently in medical circles is detail about Sims’ ground-breaking experiments and the patients upon whom they were performed. Sims apparently recorded having performed a number of experimental surgeries on enslaved women in Alabama between 1845 and 1849, and poor Irish women after he moved to New York. Over 30 surgeries were reported as having been performed on one enslaved woman alone. Sims was reported to have been a slaveowner himself – and the subjects of at least some of his experiments may have been enslaved persons he himself owned.

Over the course of the years, more physicians raised questions about the ethics of Sims’ work. His supporters downplayed the criticisms of Sims’ experiments, arguing that it is impossible today to place Sims’ work under our modern microscope to determine its ethics. And, in response to claims that Sims performed surgical procedures on enslaved women without the use of any anesthesia, his supporters claim that he began performing these ground-breaking gynecological surgeries even before the use of anesthesia was considered safe, and that he performed his first pioneering surgeries without anesthesia, on free and enslaved women, alike.

But as more questions were raised about Sims’ medical practice, more questions were raised about the appropriateness of statues, paintings and other honors awarded him. A painting that had been hung at the University of Alabama at Birmingham which depicted Sims as one of the “Medical Giants of Alabama” was removed. An endowed chair named for Sims at the Medical University of South Carolina was quietly renamed. And the statue about which I’d first read – a statue on the site of the New York Academy of Medicine – was removed in 2018.

Enter Michelle Browder. Browder was a student at the Art Institute of Atlanta over 30 years ago when she discovered a print of a painting of Sims by Robert Thom…

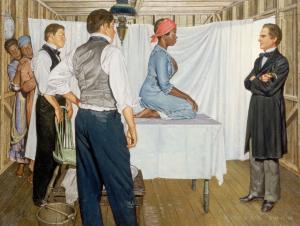

Enter Michelle Browder. Browder was a student at the Art Institute of Atlanta over 30 years ago when she discovered a print of a painting of Sims by Robert Thom, who had created a number of pieces depicting the history of American medicine. The painting showed Sims and two other white men standing around a black woman on a medical exam table, while two black women peeked from behind a curtain. Disturbed by the image, Browder began researching, and learned that Sims’ documents identified three enslaved women on whom experimental surgical procedures had been performed: Anarcha, Lucy and Betsy.

The “Mothers of Gynecology”

The discovery gave Browder the inspiration to create a group of statues commemorating the “mothers of gynecology” – the women upon whose bodies Sims had performed his experimental surgeries. Today, in Montgomery, Alabama, about a mile from a statue of Sims on the grounds of the Alabama State Capitol, Browder’s three pieces depicting Anarcha, Lucy and Betsy now serve as a teaching moment, to share the fuller history of the science of gynecology. The three pieces are sculpted of steel, and adorned with a variety of discarded metal objects which Browder found to be appropriate because the women themselves had been discarded. Browder worked with a number of artisans, and received many of the metal adornments from friends around the country.

Browder’s plans don’t stop with the commemoration of the three enslaved women. On the site of the “Negro Hospital” where Sims performed his surgeries (a building situated behind the hospital at which Sims treated white women), Browder plans to open a two-story museum and a healthcare center called the Mothers of Gynecology Health and Wellness Clinic to serve underserved women in the Montgomery area.

For a new generation of persons not trained as physicians and who were unaware of the controversy around Sims’ medical work, the removal of paintings and statues might have erased the history – and the value that comes from knowing the history.

All of Browder’s inspiration for her “Mothers of Gynecology” statues and a clinic to serve the underserved came from the discovery of a disturbing print more than 30 years ago – the image of which she couldn’t escape.

That Browder carried a disturbing image with her, determined to find a way to commemorate the enslaved women, may be one of the best testimonies for why we need disturbing images to teach us history that we wouldn’t otherwise know.

Scriptures provide us with some unsettling images of how we’ve lived in relationship with one another.

Scriptures provide us with some unsettling images of how we’ve lived in relationship with one another. So far, at least, we haven’t tossed the proverbial baby with the bathwater by suggesting that we cannot engage those scriptures for all of the uncomfortable truths they reveal about humankind:

We engage the distressing texts of Abraham passing off his wife, Sarah, as his sister – and leaving her to the hands of powerful men to do as they wished with her.

We engage the traumatizing text of Abraham leaving his firstborn son in the wilderness with his slave woman mother – with only a single skin of water, and no protection – and we engage the text of Abraham as he is about to sacrifice his remaining son.

We engage the text of the rape of Dinah.

We engage the text of David sending for Bathsheba so that he might have his way with her.

We engage the text of that same David sending Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah, to his death when Uriah wouldn’t comply with the great king’s request to go home and lie with his wife, to cover up David’s own misdeeds.

And, each year, Christians engage the text of the ultimate betrayal of a teacher, mentor and friend – followed by a state-ordered execution by crucifixion.

We engage these texts – and the disturbing images that they present us – as they help us understand more about human nature, our human shortcomings, and God’s unfailing love. We engage these texts to hold one another accountable, and to learn to live more godly and moral lives.

In the same way that engaging challenging scriptures helps us learn to live more godly and moral lives, so learning the whole of our history serves the same purpose. Had I not read about Sims’ statue in New York, my own curiosity would not have been piqued and I wouldn’t have researched and written about him in 2017.

In Browder’s case, seeing the disturbing image of a painting, and learning more about Sims and the enslaved women upon whom he experimented, meant not only finding new ways to commemorate and value the lives of Anarcha, Lucy and Betsy, but also envisioning a clinic which will be a living tribute to the ways that enslaved women’s lives have helped improve gynecological health for all women today.

Something instructive comes from the good, the not-so-good, and the downright ugly of history.

I ask again the question I asked in 2017: If we rename or remove every challenging image from our public spaces, how will we learn from history – even the more painful stories – to help us learn to live differently in our own time?