Thursday, February 1, 1968 was a cold, rainy day.

Memphis sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker likely considered themselves fortunate that day, despite the cold rain: They were at least working, and getting paid. Memphis’ black sanitation workers could be sent home on rainy days – and if they weren’t working their regular garbage routes, they wouldn’t be paid for the day.

But that day, the truck from which Cole and Walker were working was rolling through a white East Memphis neighborhood. Near the end of their shift, the men did what they usually did on rainy days, taking shelter from the rain in the back of the truck.

Except something went horribly wrong, and the compactor began running.

The two men were unable to reach the switch that could stop the compactor, and were pulled down into the barrel. The truck’s driver was unable to stop the compactor before the men were crushed to death.

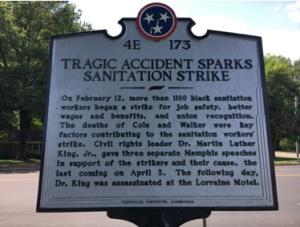

The deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker sparked outrage among black sanitation workers, who already had many concerns. Their low wages left many of them eligible for food stamps. Working conditions were poor. Efforts to unionize had been rebuffed by the city.

About the time that Cole and Walker were killed, five white Episcopalian men – four businessmen and one attorney – began having conversations about what was taking place with the sanitation workers. Fred Beeson, Charles Crump, John T. Fisher, Joe Orgill and John Salmon, representing three Memphis churches – Calvary Church, St. Mary’s Cathedral, and Church of the Holy Communion – had begun getting together for breakfast, to talk about the city. All feared that disaster would follow a sanitation workers strike. The five men were all at least acquainted with Mayor Henry Loeb, who, by that time, was apparently attending another Memphis Episcopal church with his wife.

And so these men began discussing the possibility of meeting Mayor Loeb in an attempt to broker some kind of settlement to the threat of the strike that would allow the Mayor to save face but would still give relief to the workers.

Armed with nothing more than their collective business and legal experience, the group went to meet with the Mayor. Beeson recalled that Mayor Loeb’s desk was on some kind of platform, so that everyone in his office had to look up to him. Mayor Loeb responded pretty quickly to the group: He was uninterested in talking about the sanitation workers or any of their demands.

And so the group left Mayor Loeb’s office, as Orgill put it, “having accomplished nothing.”

But the climate grew more and more tense after Cole and Walker’s deaths. On February 12, the sanitation workers went on strike. “We all feared for the future of our city,” Beeson recalled.

So the men decided to try one more thing. Having heard nothing directly from the sanitation workers, they thought that they might go and speak with them, to better understand their side of the story. The sanitation workers had made Centenary Methodist Church a gathering site; the minister there, Rev. James Lawson, was the acting chairman of the strike committee. When the five white businessmen drove up at the church and got out of their car, they realized that they were the only white people around. “It was frightening,” Beeson recalled. “We didn’t know what would happen.”

At Centenary, the five men had audience with Rev. Lawson, who explained the things that were at the core of the workers’ complaints. Beeson recounted from his conversation with Lawson that “there were really three things. First, the black workers couldn’t service the trucks; only whites could service the trucks on rainy days, so they [the white workers] didn’t lose pay on days when garbage couldn’t be collected when black workers did. Next, the black workers had no place to use the bathroom during the day; gas stations, other public places would not allow black persons to use the restroom, and the workers couldn’t go without bathrooms all day. And last, there was no place for the black workers to clean up at the end of the day. They would smell like garbage, but the showers were for whites only. They couldn’t get cleaned up before they went home.”

Beeson described the conversation as transformative for him. “I realized that these men were asking for something very reasonable, for human dignity. And I didn’t understand why the Mayor wouldn’t budge.”

Rev. Lawson remembered that meeting, too. It was, he later said, the only time that a group of white persons had come to talk to the sanitation workers. Rev. Lawson and Fisher became close friends.

On February 12, 1968, the sanitation workers went on strike. They had hoped to gain a visit from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to help draw attention to the strike. King, who had introduced a Poor People’s Campaign in November 1967, agreed that the Sanitation Workers Strike was aligned with the mission of the Poor People’s Campaign, and traveled to Memphis on March 18. Plans were underway for a march through the city on March 22, but a snowstorm postponed the plans. When Dr. King returned on March 25, violence interrupted the march, and Dr. King left Memphis for a second time. On April 3, Dr. King returned to Memphis with plans for a march on April 5. On the evening of April 3, he spoke at Mason Temple Church of God in Christ.

On the evening of April 4, Dr. King was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

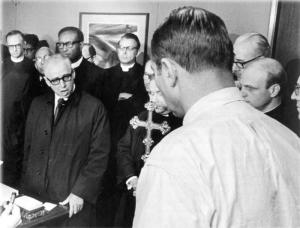

On the morning of April 5, the Dean of St. Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, the Very Rev. William Dimmick, picked up the Cathedral’s cross and led a procession of clergy and other citizens to Mayor Loeb’s office, where the group implored him to settle the strike.

Joe Orgill reflected that he and the other Episcopalian men who called on Mayor Henry Loeb “didn’t do anything.” The clergy and lay persons who marched to the Mayor’s office might have come away from that experience feeling that they, too, had accomplished nothing.

Perhaps, too often, we picture an objective, and we believe that we have accomplished nothing in spite of our best efforts when that specific objective isn’t realized. And, in doing so, we may miss the forest for the trees.

Five Episcopalian businessmen set out with a goal of putting out the proverbial fire around the Mayor’s stalemate with the sanitation workers.

Five Episcopalian businessmen came away from their efforts not having done nothing, but having learned invaluable lessons about neighbors – and respecting the dignity of all of God’s people.

And, an Episcopal priest would lead a grim procession in solidarity with the poor and underserved in Memphis.

They set examples for us all.

John T. Fisher would later say that he did what he had learned as a boy in Sunday School: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Maybe that lesson bears repeating.