Ever since I can remember, I’ve had a deep and abiding love for natural history museums. I don’t mean the revamped modern ones featuring splashy touchscreen displays, video screens, walls of informational text, and an overabundance of cartoon dinosaurs. I mean the old kind—the ones that haven’t dumped their dioramas featuring hundred-year-old taxidermy, their rows of dusty glass cases collecting interesting specimens, and their dimly lit displays of precious minerals.

Ever since I can remember, I’ve had a deep and abiding love for natural history museums. I don’t mean the revamped modern ones featuring splashy touchscreen displays, video screens, walls of informational text, and an overabundance of cartoon dinosaurs. I mean the old kind—the ones that haven’t dumped their dioramas featuring hundred-year-old taxidermy, their rows of dusty glass cases collecting interesting specimens, and their dimly lit displays of precious minerals.

In many cases, these museum collections tend to spill over from geology and biology into anthropology, displaying cultural and ceremonial objects from a variety of Indigenous peoples around the world. And this, in turn, has led to some of my most arresting encounters with the past. Once, while visiting the American Museum of Natural History in New York, I came across a suit of armor from a Pacific Northwest tribe that happened to be plaited with Chinese coins—a physical testament to a history of cultural exchange that’d never once crossed my mind.

Not everyone, though, shares my love for this sort of display. In recent years, like other cultural institutions dedicated to the preservation of the past—or, more specifically, the narration of the past from a particular perspective—many museums have been attacked as reactionary impediments to the advance of social justice. For proponents of this critique, there’s something per se objectionable in wresting culturally significant items out of their original settings so that white Western audiences can gawk at them. (The fight over the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum, a set of sculptures that once graced the Parthenon of Athens, is the best-known example of this.) And that is saying nothing of the distinctly colonial provenance of many well-known museum collections. To be sure, this isn’t an entirely novel attack—Donna Haraway was leveling a version of it as early as 1984—but it’s gained substantial ground of late.

Those museums not yet willing to dismantle themselves—that is, those museums with high attendance numbers and substantial bills to pay—have tended to respond predictably, offering up apologies and promises that they will better “contextualize” the cultural items on display. These efforts, naturally, include updating “outdated” captions and signage in favor of language rendered more sensitive to contemporary concerns.

Not long ago, I came across an interesting juxtaposition of the old and new approaches at Chicago’s Field Museum, in particular its galleries devoted to the study of Indigenous American peoples. The museum’s Robert H. McCormick Halls of the Ancient Americas, which cover American history from the Paleolithic peoples all the way to the advent of European soldiers, are sleek and modern, featuring high-dollar video screens and interactive displays alongside a dramatically curtailed selection of historical art objects. This walkthrough exhibit feeds directly into the Alsdorf Hall of Northwest Coast and Arctic Peoples, a massive gallery in the old style that’s filled to bursting with beautiful artifacts. This hall is open to the public, but one searches in vain for any mention of it on the Field Museum’s website, save for a press release that ominously describes the impending renovation of “displays that have stood largely unchanged since the 1950s.”

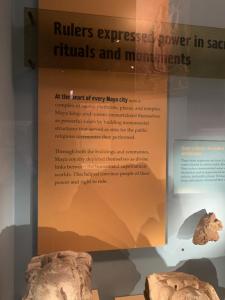

What might such renovation entail? The placard accompanying a small display of Mayan ceremonial objects, partway through the “updated” section of the exhibit, is illustrative of the philosophical presuppositions on offer.

At the heart of every Maya city was a complex of sacred platforms, plazas, and temples. Maya kings and queens immortalized themselves as powerful rulers by building monumental structures that served as sites for the public religious ceremonies they performed.

Through both the buildings and the ceremonies, Maya royalty depicted themselves as divine links between the human and supernatural worlds. This helped convince people of their power and right to rule.

Pause for a moment and reread that last paragraph. The clear implication here is that the religious commitments of Mayan civilization were fundamentally pretextual—that the Mayan elite were, to a one, covert disbelievers cynically leveraging the naïve faith of the hoi polloi to shore up their own authority. On this framing, the Mayan worldview was essentially modern, with technological advancement being the only real distinction between then and now; cultural practices are therefore to be evaluated in terms of their social usefulness rather than by reference to any higher ideals.

A brief discussion of certain Mesoamerican cultures’ practice of human sacrifice epitomizes this approach even more starkly.

A brief discussion of certain Mesoamerican cultures’ practice of human sacrifice epitomizes this approach even more starkly.

By looking across cultures, anthropologists seek to understand how and why sacrifice has played a role in the religious beliefs of many peoples throughout history and in all parts of the world. Even today, almost all world religions include sacrifice of some kind in their spiritual practices.

Some societies in the ancient Americas, like the Maya, practiced bloodletting or human sacrifice as part of their ceremonies or spiritual beliefs. Why? Anthropologists don’t fully know. One possibility is that offerings of fasting or blood may create emotional states that make people receptive to spiritual messages.

Here, the proposed range of possible explanations for the sacrificial rite is limited to the narrowly physiological. Altogether absent is any second-order analysis—whether that be René Girard’s theory of the scapegoat, Joseph Campbell’s account of the cosmic death of the Father, or even Sir James Frazer’s connection of sacrificial themes to the natural rhythms of seasonal fertility. And of course, the obvious explanation for the practice—because ancient people believed that their religion was actually true—is implicitly ruled out. For the Field Museum’s curators, it would seem that any admissible explanation for the practice of sacrifice must entail some sort of reduction of the theological-metaphysical to the therapeutic.

But interestingly, this is not the only paradigm on offer at the Field Museum. After passing through room after room suffused with hermeneutical suspicion, entering the Alsdorf Hall feels like stepping into a different world. To get a sense of the primary distinction between the two approaches, consider the following explanation of Arctic/Northwestern shamanic practices, set alongside a display of religious objects used in ritual worship.

But interestingly, this is not the only paradigm on offer at the Field Museum. After passing through room after room suffused with hermeneutical suspicion, entering the Alsdorf Hall feels like stepping into a different world. To get a sense of the primary distinction between the two approaches, consider the following explanation of Arctic/Northwestern shamanic practices, set alongside a display of religious objects used in ritual worship.

The shaman, a religious man with the ability to communicate with spirits, was called upon by ordinary people in times of misfortune—illness, poor hunting, and bad weather, for instance.

A staged performance with drumming and dancing sent the shaman into a trance. This enabled him to travel to the supernatural world where he learned the reason for the misfortune. In some cases of illness, he recovered the patient’s lost soul, returned it, and the patient became well.

It’s hard to overstate the difference between this framing and that of the “updated” exhibits. This language manages to remain agnostic about the truth-value of the Indigenous theological claims at issue while simultaneously—and this is crucial—taking seriously the sincerity of the beliefs. Altogether absent here is any attempt to reduce the shaman’s practice to merely a play for societal prestige, or a legitimation of the existing power structure; left open is the possibility of genuine differences between the metaphysical frameworks of particular cultures.

Unsurprisingly, the museum’s “updated” approach is highly reflective of currently dominant theoretical paradigms in the academy. The now-omnipresent Michel Foucault is well known for his conceptualization of human social relations, even the most apparently apolitical, as principally reducible to power differentials. And more recently, postcolonial theorist Edward Said famously denounced “Orientalism”—a “style of thought based upon an ontological and epistemological distinction made between ‘the Orient’ and (most of the time) ‘the Occident’”—as a fundamentally imperialist project inevitably oriented toward the subjugation of the Other, which has led scholars to downplay any talk of radical cultural difference between societies. Hence, the Field Museum’s “updated” take on pre-Columbian America, which collapses the thought-worlds of ancient civilizations into familiar accounts of power and privilege.

But it is far from clear that excluding the possibility of radical difference a priori really serves the goals of justice and inclusion. For one thing, there is something decidedly unbeautiful—even grotesque—about attempts to cut out the religious heart of ancient civilizations and reduce their spiritualities to merely technologies of power. Ancient visions of the world may be unfamiliar, even shocking, to Western minds, but what if our Western-secular-liberal priors are themselves misguided? Moreover, if cultures’ founding myths must be construed in strictly Machiavellian terms, it strikes me as far harder to make the case that that the languages and stories and handiwork of once-conquered civilizations are worth fighting to preserve, except as “sites of resistance” to the dominant Western ethos—and yet is it not equally cynical to deny the intrinsic beauty in these practices and reduce them to their instrumental political value?

At bottom, the “updated” approach manages to reduce genuine cultural difference to a matter of aesthetic variation within a profoundly Westernized philosophical frame. In attempting to avoid colonialist framings, the new approach inscribes a kind of neo-colonialism that demands the right to narrate non-modern cultures according to the norms of the Western humanities academy. Now, it is simply Foucault and Said and Frantz Fanon, rather than Cecil Rhodes, to whom homage must be paid; Quetzalcoatl is denied his day altogether.

Perhaps all of this sounds uncomfortably relativistic. That’s not my intent—I obviously don’t myself agree, for instance, that the sun needs an offering of blood every day to keep from going out. Rather, the point is that genuine intercultural sensitivity requires an effort to understand another tradition on its “home ground,” so to speak, rather than forcing it into an analytical frame its adherents would find profoundly alien. In the same way that I, writing as a Christian, would never see Episcopal bishop John Shelby Spong (or any other theologian who would insist that the metaphysical claims of Christianity be subordinated to the dominant categories of Western secularity) as a faithful representative of my tradition, I struggle to believe that “biopolitical” interpretations of Native culture that leave no room for the genuinely spiritual can do full justice to the depth of Indigenous faith traditions.

Suffice it to say that, in the end, I’m very sad to see the Field Museum jettisoning the “old way” in favor of a totalizing alternative paradigm, one that downplays what is most beautiful and distinctly human in history in favor of a slurry of latter-day political categories read backwards into the past. It seems to me that to take cultural difference seriously is to be confronted by the possibility of our priors being wrong—to encounter the startling possibility of an alternate way of thinking about the cosmos, one that invites us to see beyond the categories we’ve simply taken for granted our whole lives.

We are, after all, always merely creatures of our age.