And so another year—a year unlike any other in recent memory—draws to a close. Happily, I did better on the reading front than last year: right now, it’s looking like I’ll finish up around at around 250 books, substantially up from 2019’s 170. (Maybe lockdown did have its upsides, after all!) Pretty sure next year, though, is going to focus on quality over quantity: Francis Pieper’s Christian Dogmatics, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, and Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter are all up next on the docket.

And so another year—a year unlike any other in recent memory—draws to a close. Happily, I did better on the reading front than last year: right now, it’s looking like I’ll finish up around at around 250 books, substantially up from 2019’s 170. (Maybe lockdown did have its upsides, after all!) Pretty sure next year, though, is going to focus on quality over quantity: Francis Pieper’s Christian Dogmatics, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, and Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter are all up next on the docket.

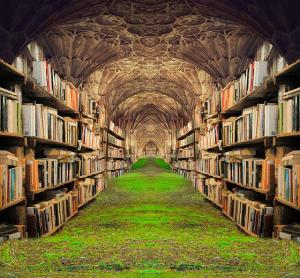

This year, I’ve increasingly tried to switch my reading habits away from ebooks and back to hard copies. I may regret that decision when I move houses someday, but for the time being I’ve learned that I retain information much better when I read it in paper form. And frankly, I don’t trust any ebook provider these days not to spontaneously edit or delete my purchased content without my knowledge. I have no interest whatsoever in buying “licenses” to access material; I want something I can keep.

So without further ado, here are the 10 books that impressed me most this year.

Pagans and Christians in the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the Potomac (Steven D. Smith)

Every so often, I stumble across a genuine paradigm-changer of a volume, and this is one such book. Smith’s argument traces the distinction between “immanent” and “transcendent” religious dispositions—that is, whether one locates ultimate value in the world of ordinary experience, or in some sense outside it. Through careful attention to historical sources, Smith convincingly demonstrates that ancient paganism was no crude polytheism, but rather a theological system built on an entirely different metaphysical vision than that offered by Christian thought. And with Christianity on the wane in the West, that once-forgotten vision has now once again come to the fore, underpinning modern debates about (among other things) human sexuality. To my mind, it’s a volume that successfully does for theological metaphysics what Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue did for moral reasoning—it provides a compelling, rigorously argued interpretive lens through which contemporary controversies make much more sense.

The Decline of the Novel (Joseph Bottum)

In this slender but intellectually rich volume, Bottum outlines a compelling case that the development of the novel—as a historical genre—has reflected the tension between Catholic and Protestant understandings of the world: the “chanson fiction” of the early Middle Ages, which emphasized social roles and civic order, and the “roman fiction” of early modernism, which focused on the interiority of its characters. Most intriguingly, Bottum presents case studies of these issues through close readings of the works of Sir Walter Scott, Thomas Mann, Tom Wolfe, and Charles Dickens. It’s a skillful blend of intellectual history and literary analysis that never fails to spark reflection.

Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life (Zena Hitz)

Is intellectual life an unjustifiable luxury in a world filled with profound suffering? That’s the question Hitz takes up in this readable and engaging book, which draws on Christian and secular literature alike to build out a stirring defense of the profoundly liberating power of introspection and reflection, when done right. Over against those demanding that every facet of life be seen through the lens of immediate political action, Hitz stresses that lasting happiness comes through cultivation of an inner sanctuary—a resource upon which one can draw regardless of their circumstances.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces (Joseph Campbell)

If you’ve heard of this book, you probably know it as the study of mythology that inspired George Lucas when he was putting together the Star Wars story. But that’s only a small piece of what Campbell has to offer. At its heart, this is a book about the universal, rational metaphysical order (dare I say “logos”?) underlying all things, and the ways in which the central elements of that order have been understood by ancient traditions from across the globe. (There’s a lot of Jungian influence here, which I decidedly did not expect when I first picked it up.) And in building out his case, Campbell lays out (probably unconsciously) a multilayered rejoinder to proponents of a thoroughgoing social constructionism that would treat every cultural norm or principle as simply one power group trying to exploit another. For Campbell, myth matters because it points to eternal truth. It’s a dense read, but well worth the time.

Mind and Body in Early China: Beyond Orientalism and the Myth of Holism (Edward Slingerland)

Slingerland’s sprawling opus may be one of the most unusual academic books I’ve ever read. First, it is a book about how to interpret the East Asian philosophical tradition. Over against Western scholars that treat Chinese culture as “holistic”—as standing beyond problematic Western conceptual binaries—Slingerland argues for the universality of a cultural distinction between “body” and “mind” that doesn’t quite rise to the level of Cartesian dualism. Second, it is a book about how to do “digital humanities” research in a way that draws on both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Slingerland makes his case for a Chinese body-mind distinction through careful use of corpus linguistics tools, which allow him to marshal immense amounts of data against rival interpreters. And third, it is a book that argues that the humanities need to take insights from science more seriously. As Slingerland frames the matter, the subject of culture is a common human organism with certain objective qualities, such that no two human cultures are completely—as in some modern critical theories—alien to one another. No matter your level of knowledge of the Chinese tradition—I’m almost a complete novice—you can benefit from this book.

The Soul of an Octopus (Sy Montgomery)

What is it like to be an octopus? That’s the question Montgomery wants to explore in this engaging, decidedly non-academic account of her relationships with the various octopuses over New England Aquarium. I’ve spent a lot of time in aquariums over the years, but even I had no idea of the astonishing array of problem-solving and recognition powers these cephalopods possess. (They’re much more talented escape artists than I ever would’ve guessed). At its heart, this book is an invitation to contemplate the genuine wonder and worth of truly alien intellects, and to ponder what insights the rest of the living world might have to offer.

The Great Believers (Rebecca Makkai)

LGBT history is not a subject with which I’m especially familiar, so it was a sobering experience to sink into Makkai’s page-turning story of the 1980s AIDS crisis. It’s one thing to read about what happened in a textbook; it’s quite another to glimpse it through the eyes of a young art curator witnessing the devastation of his community. Out of all the novels I picked up in 2020, this one might’ve haunted me most this year.

The Story of the Lost Child (Elena Ferrante)

The final volume of Ferrante’s “Neapolitan Novels”—which begins with My Brilliant Friend and continues through The Story of a New Name and Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay—is the capstone to one of the most unusual and compelling sagas I’ve ever read. If you told me beforehand that I wouldn’t be able to put down a series about the intertwined lives of two poor Italian girls during the latter half of the twentieth century, I wouldn’t have believed you. But Ferrante’s closing installment hits with battering-ram emotional force, delivering memorable payoffs for layered characters she has developed across hundreds of pages. You won’t soon forget this one.

Eifelheim (Michael Flynn)

What if St. Thomas Aquinas had met an alien? That’s not quite the scenario that Flynn’s supremely original novel poses, but it’s pretty close. When a spaceship filled with interstellar travelers crashes near a remote German town on the eve of the Black Death, monks and aliens make first contact. Some of the visitors struggle to assimilate into the local community, while others even seek baptism and engage in heroic acts of self-sacrifice. At once both a serious engagement with medieval theology and a cracking good sci-fi read, this is one you’ll have a hard time putting down.

Action Park: Fast Times, Wild Rides, and the Untold Story of America’s Most Dangerous Amusement Park (Andy Mulvihill with Jake Rossen)

Hey, we all need some fun books in our lives! In this delightful read that bridges history and autobiography, Mulvihill recounts the real-life history of a chaotic amusement park that coupled unparalleled fun with open defiance of safety protocols (and, arguably, common sense). Though Action Park may now be a relic of the past, the book is laugh-out-loud funny and a testament to the rough-and-tumble spirit of American entrepreneurism.

____________________

What are your favorite books from 2020? Please feel free to share in the comments!