Authoritative Catholic Teaching about the Bible

Admittedly, Evans’ description of “inspired” sounds significantly different, though not wholly incompatible, with the Catholic teaching of Dei verbum 11:

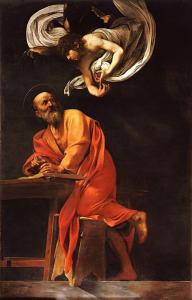

For holy mother Church, relying on the belief of the Apostles, holds that the books of both the Old and New Testaments in their entirety, with all their parts, are sacred and canonical because written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, they have God as their author and have been handed on as such to the Church herself. In composing the sacred books, God chose men, and while employed by Him they made use of their powers and abilities, so that with Him acting in them and through them, they, as true authors, consigned to writing everything and only those things which He wanted.

Therefore, since everything asserted by the inspired authors or sacred writers must be held to be asserted by the Holy Spirit, it follows that the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation.

When considering the humanity of Biblical texts, Dei verbum concludes that “the interpreter of Sacred Scripture, in order to see clearly what God wanted to communicate to us, should carefully investigate what meaning the sacred writers really intended, and what God wanted to manifest by means of their words.” To return to the Supreme Court analogy, the Catholic Church teaches originalism as the primary mode of understanding Scripture.

In opposition to proof-texting, DV advises “no less serious attention must be given to the content and unity of the whole of Scripture if the meaning of the sacred texts is to be correctly worked out.” But the language of DV is suggestive of a quest for the One Right Answer of original intent, “the correct understanding of what the sacred author wanted to assert.” (emphasis mine) While the Catechism (117) discusses the traditional framework of multiple “senses” of scripture (allegorical, moral, and anagogical), it clearly emphasises the “literal” sense as the starting point, and DV doesn’t mention these other senses at all.

These interpretive guides in DV and CCC ultimately are subordinated to singular authority, for “interpreting Scripture is subject finally to the judgment of the Church, which carries out the divine commission and ministry of guarding and interpreting the word of God.” In assigning exegetes the task of working “according to these rules toward a better understanding and explanation of the meaning of Sacred Scripture, so that through preparatory study the judgment of the Church may mature,” DV suggests that the Church aims to tell us the proper “literal” interpretation, not merely setting certain interpretations out of bounds. That said, there are no authoritative Catholic commentaries on the Bible generally. There are certain topics—like the Trinity, authority of the Pope, and ordained priesthood—where the Church gathers together a variety of Biblical texts and definitively concludes this is the intended meaning, but most of Scripture remains uncharted territory.

To Reverence or Wrestle?

Dei verbum doesn’t suggest that the lay faithful actively engage with Scriptural texts. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but DV only urges “diligent sacred reading and careful study” for the clergy, “especially the priests of Christ and others, such as deacons and catechists who are legitimately active in the ministry of the word.” The lay faithful are only told to “put themselves in touch with the sacred text itself,” and to rely on the bishops to provide suitable translations and “the necessary and really adequate explanations so that the children of the Church may safely and profitably become conversant with the Sacred Scriptures and be penetrated with their spirit.”

In other words, while Dei verbum is quite certain that the contents of the Bible are directly inspired by the Holy Spirit acting upon individual authors and the apostolic successors, it gives little attention to whether study of the Word of God is inspiring to the faithful. It concludes that “we may hope for a new stimulus for the life of the Spirit from a growing reverence for the word of God,” not “engagement with.”

I leave it to my readers to discern how much effort they may want to undertake to understand the Bible in a deeper sense than what their priests present to them, and if and how they may grapple with the “difficulties” they will inevitably encounter when they stray beyond the liturgically selective texts. I will just recall Rachel Held Evans’ insight: it is the one who wrestles with the mystery who receives God’s blessing.