The economy of grace places under judgment all economic thinking of the sort, “This is mine; I’m not sharing.”

Yesterday’s second Mass reading is social dynamite, if we have the mind and heart to take it seriously:

“For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though He was rich, for your sake He became poor, so that by His poverty you might become rich… Not that others should have ease while you are afflicted, but that as a matter of equality your abundance at the present time should supply their needs, so that their abundance may also supply your needs, that there may be equality. As it is written: Whoever had gathered much did not have too much, and whoever gathered little did not lack” (II Cor 8:9, 13-15).

The Christian Imperative of Voluntary Self-Divestment

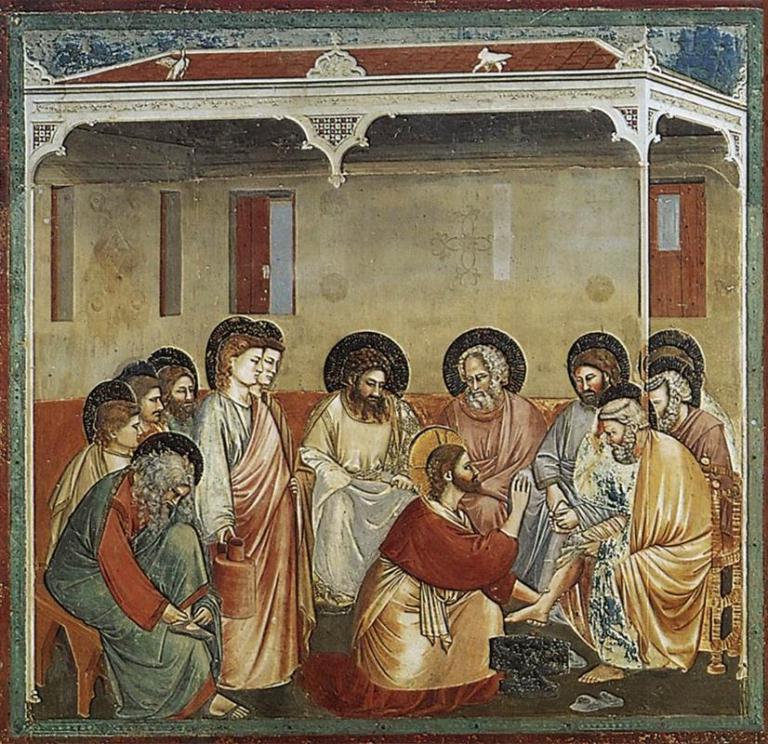

In more than one place, Saint Paul urges his Gentile converts to contribute to the Jerusalem collection, a major relief effort conducted on behalf of the Jewish heart of the young Church. In urging the Corinthians to honor their commitment to this project, Paul makes the most decisive appeal that can be made to a Christian: as Jesus has done, so we must do.

He became poor, so that we might become rich. So, we who have more, must divest ourselves of mammon’s worldly glory, for the sake of the heavenly glory in providing a most material redemption.

The social goal is explicit: equality, and the perpetual communication of a gracious solidarity.

Now, we do not here have a political question. This is an appeal to conscience. It is a social question.

It is true that we, in strict justice, owe to those who have less what we have more than enough of. There is no rulebook for this, no set table of numbers. Maintaining a manner of life becoming our station, and providing for the future of our children, are legitimate aims. But if we are honest with ourselves (if we aren’t, what good is our conscience?), there are few of us who are meeting our obligations to those who have less. The point is not to feel bad (more Catholic guilt!) The point is to let moral teaching ferment our conscience, so that we may become more and more Christlike.

Again, here we’re still talking about justice. Almsgiving, or charity, would be to cut into what we can legitimately hold onto! This is a teaching even less likely to be taught than those touching on sex.

Now, this isn’t socialism. Why? Because, though the poor have a strict right in justice to what others have more than enough of, we are not speaking of empowering the government to go around confiscating property to redistribute it (beyond a certain level of taxation, which does not exhaust the Pauline appeal). That is too much power for modern bureaucrats, who also don’t spend the money very well. Not every basic human right is to be vindicated by government. The Church has made clear that the right to private ownership of property is a real right. (Real, though non-absolute: the right to private property is meant to serve the universal destination of goods.) But the Church has also made clear that we are to use our property as if common. Again, this does not get preached on very much.

If government is not to vindicate the right of the poor to the more-than-enough of those who are better off, then all the more must we take in dead earnest our obligation to be moved in conscience to vindicate that right voluntarily. For, in any case, if we have humans starving and homeless, someone must vindicate their right to the basics of life. If we fail vis-à-vis our conscience, then we invite the government to step in.

Eucharistic Redistribution

The last sentence of the lectionary reading is a quotation from Exodus 16:18: “Whoever had gathered much did not have too much, and whoever gathered little did not lack.” This refers to the miraculously redistributive quality of manna, and should remind us of one of the essential aspects of the Eucharist: it drives towards social equality. Betraying that drive makes us unworthy of communion (see I Cor 11:17-34).

And this is not social dynamite to be contained within the Church: everything Christian is catholic; it presses towards universality.

We cannot merely take care of those in our own parishes who are struggling (though we don’t do the best job of even that). Suburban parishes must look to relieve inner-city parishes. Wealthier parts of the country must feel responsible for the poorer parts. White congregations should take real care of minority populations.

And we must also make provision for Catholics beyond our borders. (The Romans and Greeks of Corinth were helping the non-Roman-citizens of Jerusalem. It was the “international law” of ius gentium that governed relations between the peoples of the Empire. Charity and justice did not stop at the boundaries of proto-states, nor should they stop at the boundaries of the nation-state—a late, but necessary, invention of modernity.)

Indeed, we should take care of anyone, Christian or not, who is in desperate need.

Let’s not call it socialism, this divestment of our more-than-enough for the sake of general equality and an elevating exchange of gifts. It’s simply the following of Jesus and the economy of grace. Let’s call it Christianity.