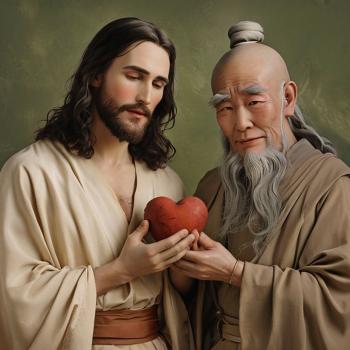

How are Jesus and Lao Tzu like Reece’s Peanut Butter Cups? They are the two great faiths that faith great together!

Do you remember the old TV commercials where two cowboys sit by the fire? As they accidentally bump into each other snacks collide. Each one looks to the other with furrowed brows. “You got your chocolate in my peanut butter,” the first one drawls. The second, just as offended, says, “You got your peanut butter on my chocolate!” The viewer wonders if a dust-up or gunfight might ensue. Then, as if a lightbulb turns on over their heads, they realize they’ve serendipitously come up with a great creation. The announcer says, “The two great tastes that taste great together—Reece’s Peanut Butter Cups.”

It was the same for me when my ninth-grade World History teacher introduced our class to Taoism. I felt like one of those cowboys by the fire. “Hey—you got your Lao Tzu on my Jesus!” Later, it was as if my university Taoism professor said, “You got your Jesus in my Lao Tzu!” Taoism and Christianity were the two great faiths that faith great together.

How Jesus and Lao Tzu Agreed

If Lao Tzu and Jesus had been schoolchildren concurrently, they would have played well on the playground together. As Jesus criticized the religiosity of the Pharisees of his day, Lao Tzu critiqued the scrupulosity of his contemporary, Confucious. Both teachers emphasized the simple life, uncomplicated by striving and ambition. They both teach detachment from worldly things, yet a mystical connection to everything. Each in his own way either taught or displayed the flow of sacred energy pervading all living things. They agreed that learners learn best by unlearning and reducing their minds to that of a child or even an infant. In fact, the two sages agreed on more than they might have disagreed.

Where They Disagreed

Of course, undeniable differences exist between the worldviews of the Jewish carpenter and the Chinese philosopher. Yet, the areas where they overlap intrigued me as a young student and continue to haunt me today. As I write, I aim not to draw a strict parallel between Christianity and Taoism. Trying to fit a square peg into a round hole isn’t very Taoist, after all. Instead, I hope to highlight areas where Jesus and Lao Tzu are compatible and to show that a person can honor both at once.

As you take this journey with me into the teachings of Lao Tzu and Jesus, you’ll discover some key principles and terms relevant to Taoism. Here’s an excerpt from my chapter on Neo paganismand Taoism in Sitting in the Shade of Another Tree: What We Learn by Listening to People of Other Faiths, in which I discuss these key concepts:

Wu-Wei

In Taoism, Wu-Wei means non-doing or non-action. Western culture teaches that the most effective thing is to be busy. But sometimes non-action is the best course. I’m not talking about inaction, where a person gets so frozen by indecision that they can’t do anything at all. I’m talking about non-action, which calmly fosters life and growth. Taoism uses water to symbolize this flow.

A lake, a river, and the ocean all have their own kind of Wu-Wei. The virtue of a lake is in its non-action. It isn’t going anywhere…but it is teeming with life beneath the surface. A river is in motion, but it practices Wu-Wei as it follows gravity downhill and remains within its watercourse. An ocean is even more active, yet it practices Wu-Wei by allowing the moon to exert its gravity. It permits water to leave through evaporation and cloud formation and welcomes the water’s return through the rivers. The ocean doesn’t strive to become the most life-giving force on the planet—it simply is.

In the same way, when we placidly practice Wu-Wei, we offer life to those around us. By our own non-action, we offer a sense of peace. People know they can come to us with their own problems when we can remain as untroubled waters. I think about the Wu-Wei of the ocean when the Roman emperor Caligula purportedly declared war against Neptune and struck at the waves with his sword. Beat and slice the water as he might, the Roman could do no damage to the sea. All the sea had to do was rest and be the sea. Practicing non-doing allows me to withstand the world’s attacks relatively unscathed and able to offer life in response to violence.

In both the martial and exercise forms of Tai Chi, we learn to move through the practice of Wei-Wu-Wei (Doing without action). This means minimal effort for maximal results. It means not responding to aggression with aggression but remaining placid even when threatened. When attacked, you side-step. You flow around your opponent, moving in from behind like water filling in the gaps. You allow your attacker to throw themselves off balance. In college, my Taoism professor and my Aikido master both taught me to flow—to be soft, like water. It isn’t just a martial art move—it’s a way of life.

Jesus expressed this as “living water” which gives life and rises up within the believer. In youth group, we sang, “I’ve got a river of life flowing out of me.” I heard it in church perhaps so much that it lost its meaning. Sometimes when you hear the same thing using different words, it underscores what you already learned. Taoism did that for me. It took the teachings I learned in church and rephrased them in a way I could understand. Through Taoism and the practice of Tai Chi and Aikido, I learned about the flow of all things.

I found this go-with-the-flow philosophy of Taoism helpful in all aspects of my life. It has much in common with the serenity prayer: “God give me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” I could work myself into an early grave, developing all kinds of attachments to the outcomes of my vocation. But, by learning to flow as Jesus did, I can not only survive but thrive at work.

The Charismatic and Pentecostal traditions refer to this liquid approach to faith as “flowing in the anointing.” You know you are flowing in the anointing when your work is effortless, like water moving downhill in its own watercourse. The psalmist calls this liquid movement “harmony.”

How wonderful and pleasant it is

when brothers live together in harmony!

For harmony is as precious as the anointing oil

that was poured over Aaron’s head,

that ran down his beard

and onto the border of his robe.

Harmony is as refreshing as the dew from Mount Hermon.

This harmony represents the movement of the Holy Spirit, which also describes the flow of Tao. When a Christian is baptized, they are initiated into this Way of flowing. John the Baptist prophesied that Jesus would baptize with “Holy Spirit and fire.” This dual flow is like water or wind, but it is also energetic, like fire, something that Taoism calls Chi.

Chi

In Taoism, another important concept is Chi or energy that flows from consciousness. Chi is a gentle yet powerful force within all creation. Tai Chi and Aikido involve the exercise of this power in the human body. In subtle ways, Chi can be found in the Bible. The Jewish prophet Jeremiah said, “There is something like a burning fire shut up in my bones.” Jesus gave an example of this flowing energy. When the woman reached out to touch the hem of Jesus’ garment, it healed her immediately. Jesus said, “Someone deliberately touched me, for I felt healing power go out from me.” On the day of Pentecost, tongues of fire appeared on the disciples’ heads, energizing them for ministry. This was a visible example of fiery Chi, flowing from them.

Reflecting the divine image, human beings flow with this sacred fire that Taoists call Chi. It can be an instrument for destruction or for healing. Martial artists use Chi to win a fight, while practitioners of acupressure, acupuncture, and Reiki use the same energy to heal. Often, I have felt this flow of this holy power when laying hands on someone in prayer. Christians believe in Chi—our scriptures teach it and our practices support it. We just usually call it something else.

Pu

The concept of Pu, or the uncarved block, is an important one in Taoism. As a behavioral health specialist, I find this important as I meet with people to listen to their problems. The uncarved block is a symbol of openness and receptivity. It can become anything. It has limitless potential until it starts to be carved. If a block of wood comes before its carver with preconceived notions or intentions of being carved this way or that way, then it limits its own potential. When listening to the problems of others, I have learned to be like Pu…. When I approach someone as a blank canvas, a clean slate, or an uncarved block, then I can hear their concerns without disrupting my own ego, emotions, or predetermined thoughts. When a person walks through life practicing Pu, then they approach everything with a sacred curiosity. Rather than rigidly deciding in advance, they are receptive.

A Taoist Concept of God

While I generally relate to the divine Parent in a personal way, there are also times when I need a more Taoist concept of God. I can have a personal relationship with Jesus while also knowing God as a natural, constantly moving force of love. The Tao and Chi are similar to the Holy Spirit, a personage without a name or a gender. Certainly, Christianity describes God as a personal Being, but it also describes Ultimate Reality as a breath of wind, a holy fire, a living water, the Ground of all Being. God is big enough to encompass both the personal and the impersonal—like Yin and Yang swirling together.

In Taoist philosophy, there is no concept of a personal deity. You might say, however, that Taoists believe in the Way with a capital W, Truth with a capital T, or Life with a capital L. Rather than mere concepts, these are animating forces, universal and sacred principles of being by which we live. While Christians often describe God as a Divine Person, there is also a great benefit to understanding God as the Tao.

With a divine Person, we cry out to God in times of anguish and despair. We plead with a heavenly Parent who we expect will be moved by our tears. We worship God with uplifted arms and shouts of joy. There is nothing wrong with relating to the Infinite this way. Jesus taught us to pray, “Our Father, in heaven.” Many people talk about knowing Jesus personally, and not just as a character in the Bible. I have had many very personal experiences with Jesus, myself. Through God the Parent and Christ the divine Child we get a picture of a personal God. Yet, it’s also within the scope of Christian practice to relate to God as something other than personal.

The Bible often refers to God in non-anthropomorphic terms. More than a heavenly Person, God is the One in whom “we live and move and have our being.” You might say that God is the ocean in which we swim. God is “All in All.” When Moses asked the name of God, the Almighty responded, “I AM that I AM.” In other words, “I am the Essence of Existence Itself.”

Employing this “I AM” language, Jesus said, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” One viable interpretation is that Jesus is the embodiment of this Great Force, which manifests as the Way (Tao), Truth (Pu), and Life (Chi). No one comes to the Source except by this path. Rather than mere concepts, the Way, Truth, and Life are principles of being by which we become immortals ourselves.

You might ask, “Why would a Christian exchange the belief in a personal God with the notion of an impersonal Force?” Because it helps answer the problem of suffering and evil. I can’t tell you the number of times people have asked me, “Why would an all-powerful, all-loving God allow suffering? Since there is suffering, that means that either God is powerless to stop it, or unloving enough to permit it.” This question is only a problem to those who think of God in terms of a divine Person. When you see God as a universal Principle—as Tao, you stop asking the question altogether.

Understanding God as Tao also answers the problem of seemingly unanswered prayer. Many say that “God answers my prayer with a yes, no, or wait a while.” Yet, this presumes a capricious King making arbitrary decrees, a Judge influenced by constant begging, or an all-wise Parent who silently keeps their wisdom to themself. I’ve known people who nearly lost their faith after praying for loved ones to be healed, only to watch them die in agony. In the end, they concluded that God was not a heavenly King, Judge, or Parent who could be manipulated by name-it-and-claim-it prayers. Instead, by relating to the Most Sacred as the Essence of all Being, they could maintain their spirituality while no longer expecting wishes to be granted from on high.

For me, though, it isn’t a question of either-or. It’s more like both-and. I relate to the Sublime both as “God in three Persons, blessed Trinity,” and also as the Alpha and Omega, Existence Itself, or the Word. God is both personal and impersonal. Like the swirling Yin-Yang with its two dots, the impersonal contains a bit of the personal within it, and vice versa. Besides the Taoist symbol, the cross also illustrates this point. The vertical axis emphasizes the relationship between a personal God and humanity, while the horizontal axis represents the cosmic and impersonal Power that reconciles and binds the entire universe. For me, God is both the loving Parent into whose lap I can crawl, as well as the Ground of all Being, my All in All

Two Great Faiths That Faith Great Together

So, for me, mixing Taoism and Christianity came as naturally as blending chocolate and peanut butter. They are the two great faiths that faith great together. Taoism explains some aspects of faith and religion that Christianity doesn’t seem to answer. And Christianity’s emphasis on unconditional love contributes something valuable to the ever-impersonal Tao.

The young Jesus likely encountered China’s Taoist merchants on trade routes throughout the Levant. So, it should come as no surprise when we find Taoist principles reflected in the rabbi’s teachings. However, I would be mistaken to claim that the philosophies of Jesus and Lao Tzu are the same. It’s better to say that they share a remarkable compatibility. It is at the crossroads where Jesus and Lao Tzu meet that I have found my faith.

People of All Faiths and No Faith

I write this for Christians in the East and West who, like the original disciples, want to follow Jesus as the eternal Way. I also write this for aficionados of Chinese philosophy who seek to understand Western faith through the lens of Lao Tzu. Further, I hope this will be interesting to people of all faiths and no faiths who want to liberate spirituality from religion. Walking the Way of Lao Tzu and Jesus doesn’t mean abandoning the sacred truths that make you own religion unique. Instead, it means stepping into the river of living water that surrounds, fills, guides, and unites the universe. As I begin this article series, I hope you’ll join me as we follow this sacred Flow.