I remember May Day celebrations as a child—a festooned pole in the schoolyard, with children dancing around it. How did this get started?

As Christianity expanded from the Roman Empire into Celtic lands, it encountered religious practices it did not understand. This earth-based spirituality predated Roman Catholicism by hundreds, if not thousands, of years. When missionaries strategized to convert the “heathen” inhabitants, they determined the best way was to adopt and adapt indigenous practices into the Church. This series, “Christian & Pagan Holidays” will cover all eight observances in the Wheel of the Year. It will examine the relationship between pre-Christian celebrations and their subsequent adaptations.

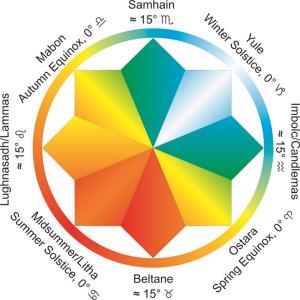

The Wheel of the Year

In the first of these articles, I wrote:

Pre-Christian Celts divided the year into eight equal portions, called “The Wheel of the Year.” The quarters fall at the summer solstice (Litha, on or around June 21), the winter solstice (Yule, on or around December 21), spring equinox (Ostara, on or around March 21), and fall equinox (Mabon, on or around September 21). The cross-quarters lie at the midpoints in each season. The midpoint of spring is Beltane, on or around May 1. The middle of summer is Lughnasadh, on or around August 1. Halfway through fall is Samhain, on or around November 1. The midpoint of winter is Imbolc, on or around February 1. (These dates are inverted for those who celebrate in the southern hemisphere.) Each of these quarters and cross-quarters represents a different phase in the agricultural year and carries with it a spiritual significance.

When Roman Catholicism entered the unchurched lands of Western Europe, it Christianized the indigenous festivals to facilitate the conversion of Pagans. Ostara was renamed Easter. Beltane was transformed into May Day with its fertility pole. Litha corresponds to the Roman Catholic Solemnity of the Birth of John the Baptist. Lughnasadh, the festival of first harvest, became Lammas, or the Loaf Mass. Mabon, the feast of the second harvest, became the Feast of Matthew the Apostle. The Church turned Samhain into All Saints’ Day. We are more familiar with the day before—All Hallows Eve, or Halloween. Christmas eclipsed Yule to such an extent that many think they are synonymous. And finally, Candlemas replaced Imbolc.

At the beginning of this series, I wrote about Groundhog Day, Candlemas, and Imbolc. Next, in “Easter Bunnies Come from Ostara,” I focused on Easter traditions. Today, we focus on Beltane, or its post-conversion name May Day. I’ll look at its significance to pre-Christian Celts. I will discuss some practices of modern Neopagans. And I’ll ask if it’s okay for Christians to celebrate May Day. Granted, May Day is not a major holiday like Yule/Christmas or Ostara/Easter. But we benefit from understanding its place in religion and history.

The Origins of Beltane

The cross-quarter celebration of Beltane marks the halfway point between the vernal equinox and summer solstice. The days are progressively getting longer and warmer. Flowers are in bloom, and seeds have begun to sprout. The name “Beltane” means “Bright-fire,” or “Bel’s fire,” referring to the sun god Bel. Religion Media Centre reports:

Several early Irish sources, including Cormac’s Glossary and the Wooing of Emer suggest that two fires were lit at Beltane and cattle driven between them for protection and blessing. This practice continued in a number of places into the 19th century. Other common customs were the decorating of a May bush, often a hawthorn, which was carried in procession. The cutting of thorn bushes at any other time of year was often considered unlucky. In some places bannocks, a flatbread, were baked on the Beltane fire and portions distributed.

Customs associated with May Day, such as the ’Obby ’Oss Festival in Padstow, Cornwall; dancing around a May pole, crowning a May queen; dressing wells; and bringing May blossom into the house are widely celebrated around Britain, although many of these were revived during the 20th century rather than being medieval survivals. In this way, Beltane is celebrated more widely than just in Pagan communities.

First and foremost, Beltane is a fertility holiday. From crowning a young woman with flower blossoms (pistils and stamens in full flourish) to Maypoles to Beltane fires, the whole point of the festival is to focus on fecundity.

Sympathetic Magic

Here, we find a good opportunity to look at the practice of sympathetic magic, the concept that “like attracts like.” Practitioners believe that in the same way they perform a symbolic action in the physical world, they produce a similar effect in the spiritual or unseen realms. We see this in the phallic imagery of the Maypole, with virgins dancing holding the “ribbons” that flow from the top of the phallus. Essentially, they were saying, “As the young women dance around this symbolic penis, may they become physically pregnant and bear many children.” This focus on fertility also shows in the holiday’s popularity with those getting married or becoming “handfast.” The desire for sexual potency applies to livestock also, enacted by the sexual imagery of driving cattle between the two fires.

Sympathetic Magic in the Bible

Christians may believe that sympathetic magic is a primitive tool only used by pagans. But there’s plenty of it in the Bible, as well. Take, for example, Jacob’s breeding strategy in Genesis 30:37-43. He cuts fresh staves and peels some of the bark, exposing white and dark streaks in the wood. Then he places those rods in front of the watering places. When the flocks come to drink (and to breed), they give birth to striped, speckled, and spotted sheep. This way, Jacob magically breeds his flocks to distinguish them from his father-in-law Laban’s white sheep. In this case, like Beltane, we see sympathetic magic employed to encourage fertility.

Or consider 2 Kings 6:4-7. A friend’s axe head has flown off the handle and splashed into the river. To recover the heavy object, the prophet employs sympathetic magic. Remember, “like attracts like.” So, Elisha throws a stick into the water, so that its buoyant properties are magically transferred to the axe head. Sure enough, the iron implement floats to the surface.

Lest we think these things only take place in the Hebrew Bible, let me direct you to Acts 19:11-12, where we read about the apostle Paul’s healing handkerchief. Handkerchiefs are used for wiping sweat, snot, and other unmentionables. Therefore, they represent the cleansing of disease. By sending a prayer-blessed hanky, Paul employs sympathetic magic. “As above, so below,” the Pagans say—but Christians believe it, too. And so, all who receive Paul’s special hankies are healed.

Neopagan Beltane Traditions

Uncomfortable as medieval Christianity was with magic of any kind, it makes sense why the Church downplayed this important Pagan holiday. By the nineteenth century, Beltane sputtered out like a dying fire. The Beltane Fire Society gives a history of Beltane’s demise:

In Scotland, the lighting of Beltane fires – round which cattle were driven, over which brave souls danced and leapt – would survive into modern times, although a process of slow decline saw towns and villages slowly abandon the practice in the nineteenth century. The last Beltane fire recorded in Helmsdale took place in 1820. In the middle years of the century the fires of Fife spluttered out, and by the 1870s they would go unlit in the Shetland Isles. By the start of the twentieth century, Edinburgh, which had for time immemorial seen beacons lit on Arthur’s Seat, ceased such public Beltane celebrations.

Yet, the website also discusses the holiday’s reemergence, like a phoenix from its ashes. Seasonal Soul observes that while modern Paganism draws inspiration from its ancient Beltane celebrations, the current practice adds a contemporary view of sex, sexuality, and women’s sexual agency. The holiday reminds observant people that, for most people, sex is sacred and is part of being alive.

We’Moon, a website celebrating the sacred feminine, suggests that women take time at Beltane to track their cycles. It’s a time for working spells for fertility and love. Maypoles, flower crowns, and fires may be part of this. It’s also a time for contact with the spiritual realm because many believe that, like at Samhain, the veil between worlds is thinnest. Dhruti Bhagat writes, “Some people prepare ‘May baskets,’ and fill them with flowers and goodwill. They give the baskets to someone in need of care, such as an elderly friend, or someone who is recovering from an illness.”

Is it Okay for Christians to Celebrate May Day?

Many churchgoers discuss whether it’s okay for Jesus’s followers to celebrate Halloween. Almost nobody asks whether Christians can celebrate May Day. Perhaps if they knew the holiday’s origins, they would ask that question. Certain brands of Christians superstitiously avoid anything with Pagan origins, ditching many of the best things about Christmas and Easter. By now, though, Christianity is inextricably linked with pre-Christian paganism, as much as it is tied to its forebear, Judaism. You might say that Judaism + Jesus + European paganism = modern Western Christianity. By now, it’s hopeless to try to unmarry this happy trinity. So, sure—it’s fine for Christians to celebrate May Day.

How Can Christians Celebrate May Day?

What are some ways Christians can observe this halfway point of Spring? Here are a few suggestions:

- Plant flowers in your yard, at your school, or in a balcony planter box. Remember the specific needs of pollinators like bees and hummingbirds. If you have room on your property, consider starting a beehive. This promotes the ongoing life and fertility of our planet.

- Give homegrown flowers to those you love. Remember, flowers aren’t just for Valentine’s Day. They convey “I love you” all year long. But be mindful of the ethical considerations of the cut flower industry.

- Understand that, historically, the Church has been down on sex. Ask yourself what it would mean for a Christian to be sex-positive. How would a sex-positive attitude improve your relationship with your spouse, children, and others? (If you don’t know what sex positivity is, here’s a good link to start learning.)

- Use the opportunity Beltane offers to educate yourself about intersex and asexual individuals, and how the church should include them.

- Take the occasion provided by May Day to teach young people about sexual ethics and healthy sexual boundaries, including enthusiastic consent.

- Consider what it really means to be consistently “pro-life.” Many believers use the term “pro-life” to mean that they are anti-abortion. Yet, (Americans) do you support universal healthcare that would promote health for the baby, her mother, and her father once she’s born? Do you work for stricter gun laws that would protect him when he goes to school? Do you affirm LGBTQIA+ individuals, thereby reducing their suicidality? Do you promote pacifism, in the dream that one day war may be a thing of the past? If you say that life is sacred, do you advocate for voluntary dying with dignity, so our elders may live abundantly as long as they live? Take some time to ponder these things—if you claim to be “pro-life.”

May Day is Different from “Mayday!”

Christians are free to join their Pagan sisters and brothers as they celebrate the first day of May. Just remember—May Day is different from Mayday! Or, at least, I hope it is—here’s what I mean. According to Rhik Kundu, “Mayday!” is a distress call that originated in the 1920s. It comes from the French phrase, “m’aider” which means, “Help me!” I hope that by thoughtfully celebrating May Day, Christians can avoid a distressed “Mayday!” from the whole planet. May Day is a celebration of life at its most basic level. By suggestions like those I’ve made above, Christians can come to Earth’s rescue.

A Final “May” Day Thought

To conclude, I’d like to offer one final thought for May Day: In your mind, utilize those little quotation marks and call it “May” Day. This is a good month to learn the dangers of cursing and the blessings of blessing. In an act of sympathetic magic (or, you might call it prayer), practice saying, “May” this good thing happen to you, or “May” that blessing come into your life. You can make it a month to change your vocabulary so that you speak words of benediction to everyone.

A Franciscan Blessing

So, at this midpoint of Spring, I leave you with the Franciscan blessing that epitomizes the best use of the word “May.”

May God bless us with discomfort

At easy answers, half-truths,

And superficial relationships

So that we may live

Deep within our hearts.

May God bless us with anger

At injustice, oppression,

And exploitation of people,

So that we may work for

Justice, freedom and peace.

May God bless us with tears

To shed for those who suffer from pain,

Injustice, starvation and war,

So that we may reach out our hands

To comfort them and

To turn their pain into joy.

And may God bless us with enough foolishness

To believe we can

Make a difference in the world,

So that we can do

What others claim cannot be done.