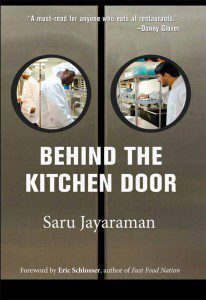

Sara Jayaraman’s book Behind the Kitchen Door (Cornell University Press, 2013) is this year’s Unitarian Universalist  Association Common Read, a book chosen annually for all UUs to read, discuss, and potentially act on. The book is dedicated “To the more than 10 million restaurant workers nationwide, who struggle daily to feed us.” I recommend this important book as well to all who eat in restaurants and care about the fair treatment of restaurant workers.

Association Common Read, a book chosen annually for all UUs to read, discuss, and potentially act on. The book is dedicated “To the more than 10 million restaurant workers nationwide, who struggle daily to feed us.” I recommend this important book as well to all who eat in restaurants and care about the fair treatment of restaurant workers.

And early on the author tells the story of what she called her “Matrix moment.” You may recall in the first Matrix film that the main character Neo has a transformative moment when he suddenly begins to see a much more complex reality behind the façade that he’d experienced previously as much a simpler ordinary reality. Jayaraman’s Matrix moment was the shift from taking restaurants and going out to eat for granted (as a simple, ordinary part of reality) to looking behind the kitchen door and becoming involved in the struggle for social and economic justice for workers in the restaurant industry. She writes that:

After that, every time I ate out I would look in the kitchen. For the first time, I saw every kitchen worker, every restaurant worker, as a human being, with a unique story, family, dreams, and desires. I would see these workers every time I ate out…. Suddenly I could see a whole world I have never seen over a lifetime of eating in restaurants. (11)

My experience reading her book was similar: I became more aware of social and economic justice issues related to eating out at restaurants that I hadn’t considered previously in such depth and I now know some concrete ways that we individually and collectively can make a difference to improve the lives of restaurant workers around our country.

I had a related Matrix moment during my second year in divinity school at TCU in Fort Worth, Texas. Periodically, a speaker would be invited to address the seminary community over lunch, and the administrators would entice students to show up by giving away free pizza. As you may know, free food has an almost magical power of attraction for many students.

At the lunch in question a little more than a decade ago, the speaker was Tara Pope. I had never heard of her before, and as she stepped up to the microphone she could have easily passed for an average TCU student — young, blonde, white female — with one major exception: she was wearing the heavy-duty, outdoor uniforms worn by the university’s mostly older, Latino and Latina building and grounds crew.

As it turns out, Tara had graduated TCU two years earlier as a religion major. And needing a summer job after graduation, she applied to work for the building and grounds crew. She figured it was a good way to spend the summer outside, and have an excuse to stick around her alma mater. And she did find the work itself rewarding, but as she learned more about the lives of her co-workers, she was disturbed that their year-round hard labor still left many of them impoverished or in need of government assistance for their families to even scrape by at a subsistence level.

Using her privilege as a former TCU student, she began organizing a Living Wage campaign for campus employees. She had planned on a summer job, but stayed in solidarity with her co-workers. (That’s the part of the story when I started to sit up and pay attention. I remembering thinking, this is a twenty-four year old taking a fairly radical and usual step of really making a difference with her life through solidarity with a marginalized group. She also, by the way, began tutoring her co-workers who asked her in English as a Second language.) And within two years of starting work for the TCU Physical Plant, Tara had helped raise base wages from $7.25/hour to $8/hour. Despite that improvement, however, at that time, “according to the national Universal Living Wage organization, the estimated living wage for renting a one-room apartment in the Fort Worth area [was] $10.50 an hour.”

One definition of a Living Wage is an hourly rate given the cost of living your community such that, “if you are willing and able to work a 40 hour week, you should at least be able to afford a one-bedroom apartment.” For example, MIT’s Living Wage Calculator estimates that, a single adult without children living in Frederick County (where I live) would need to earn $13.20/hour to have a Living Wage, which is almost $6 more than the current $7.25 minimum wage. A single adult with one child needs to earn $25.02 for a Living Wage. And in that scenario, the $7.25 minimum wage is a mere 25 cents more than a poverty wage.

Like Jayaraman’s “Behind the Kitchen Door” epiphany from helping organize a protest for restaurant workers, Tara’s speech at that lunch gathering was a Matrix moment for me. And just as Jayaraman could no longer take restaurant workers for granted (and began to more fully see each worker’s humanity and “unique story, family, dreams, and desires”), I could no longer walk past the buildings and grounds crew of the university without remembering their struggle for a decent, sustainable, fair wage in exchange for a full day’s work. One small step no long afterward was speaking with our Latina Feminist Theology professor about finding a place where I could volunteer to teach ESL, which I did until graduation.

And to expand our vantage point, here’s how that Living Wage campaign at TCU relates directly to the plight of many restaurant workers across our nation today, Jayaraman writes that,

Restaurant workers hold 7 of the 10 lowest-paying occupations in the United States, earning less, on average, than farmworkers and all other domestic workers…. In 2010, the median wage of restaurant workers nationwide was $9.02/hour, including tips…. In 2009, restaurant workers made, on average, $15,092 [for the year]. (71)

As a result of these unjustly low wages, Jayaraman notes the “discomforting irony [that] servers in the restaurant industry use food stamps at almost double the rate of the rest of the U.S. workforce. Should taxpayers really be subsidizing the restaurant industry, which is growing so rapidly, to allow its employees to eat?” (84)

Relatedly the forward to Behind the Kitchen Door is written by the food justice activist Eric Schlosser, known for his book Fast Food Nation, which was an exposé of the health, environmental, and animal rights consequences of how much of our fast food is produced. Schlosser points out the deep connection between caring about healthy, sustainable, local, organic food and caring about fair, just, sustainable wages and benefits for the human beings who serve that food to us at restaurants (ix-x).

As Jayaraman notes, many of us have reached a point where it is second nature to ask those underpaid, poorly-treated restaurant workers about whether the food on the menu is fair trade, local, humanely-raised, etc. And she has a strong point that we need to learn to ask a similar set of questions about whether workers are treated in human and sustainable ways (172-3). Specifically, Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (or ROC-United), the organization Jayaraman co-founded, produces a free annual “Diner’s Guide to Ethical Eating” that suggests five specific areas that are most helpful for patrons to ask about behalf of restaurant workers:

- Do you pay tipped workers a base wage of at least $5/hour? That’s 70% of current minimum wage. It’s important to note that, “Since 1991, the federal minimum wage for tipped workers has been frozen at $2.13 an hour.”(“Tipped workers include servers, runners, bussers, bartenders, barbacks, and expeditors.”)

- Do you pay non-tipped workers at least $9/hour?(“Non-tipped workers include host/hostess, dishwashers, prep cooks, line cooks, and porters.”)

- Do you provide all your employees with paid sick days? This question is important because disturbingly, “Over 90% of the more than 4,300 restaurant workers…surveyed report not having paid sick leave…[and] two-thirds of those surveyed report to work and prepare, cook, and serve food while sick.” Thus, just as local, sustainable, organic, fair trade food production results in healthier food for us consumer, so too do sustain, fair, just working condition for restaurant workers result in healthier dining experiences.

- Have at least 50% of your current employees been promoted internally?This question discouragesthe treatment of restaurant workers as disposable and replaceable and encouragesrestaurant work as a sustainable career in the hospitality industry.

- Does your restaurant belong to ROC’s Restaurant Industry Roundtable, “a group of employers working to promote the high road to profitability in the industry?”

And if you are wondering, in regard to what restaurants meet some or all of the above five criteria, yes, there is an app for that! The website of Jayaraman’s organization, ROC-United, has a link to their free smartphone app that will help you find restaurants that they have awarded their silver prize for answering “yes” to at least two of those five question — or their Gold Prize for answering “yes” to three of those five questions.

Part of the problem for now, however, is that this grassroots movement for restaurant worker justice is most prominent in ten major cities (the Bay Area, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, Detroit, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, Washington D.C.) So, unless you live in or are traveling to one of those cities, you unfortunately can’t yet use the app or restaurant guide to evaluate restaurants in your hometown. But in the meantime, you can begin to spread the word about Jayaraman’s book Behind the Kitchen Door, the free Diner’s Guide app, and the ROC-United website with the owner of your favorite restaurants and with anyone you know in the restaurant industry to begin raising awareness about the widespread injustices in the industry as well as the concrete steps that are being taken to create change. In so doing, we can help more restaurant workers outside of major cities to organize and advocate for fair treatment.

Closer to home you can also visit the website dignityatdarden.org to learn about the current action ROC-United is mobilizing to put pressure on unjust practices in the Darden Restaurant group, “the world’s largest full-service restaurant group, including popular chains such as Capital Grille as well as Red Lobster, Olive Garden, and Longhorn Steakhouse, and more.” That title “Dignity at Darden” resonates deeply with the UU First Principle of the “inherent worth and dignity of every person.” And if ROC-United is successful in creating change at the Darden Restaurant group, we could see a domino effect on smaller chains.

I already see evidence that change is possible in how swiftly we’ve seen restaurants shift in the last few decades. It wasn’t that long ago that you almost never saw a reference on menus about whether an item is vegetarian, vegan, gluten-free, locally-sourced, fair trade, organic, etc. Now you seen that almost everywhere. Restaurants made the shift as customers’ questions made clear that they wanted these options and were willing to pay more for them. And ROC-United is right that there is real potential for consciousness raising — that treating working with cruelty is as equally unhealthy and unsustainable for everyone concerned in the long-run as mistreating animals and the environment.

And the good news is that change is already happening. The New York Times ran an article a few months ago about major, established, trend-setting restaurants around the country who have stopped taking tips, and are incorporating that cost into the price listed on the menu or as a surcharge. One restaurant communicates this change with a note at the bottom of the check which says, “Service staff are fully compensated by their salary. Therefore gratuities are not accepted.”

This article also mentions another vital contributing factor to the movement for restaurant justice: the increased use of credit cards. One reason restaurant workers likely did not organize earlier against the federal minimum wage for tipped workers staying at $2.13 for the past twenty-two years is that when tips were in cash, they were not necessarily reported on income tax returns. But now that tipping on credit cards is almost ubiquitous, those electronic tips leave a paper trail. Ironically, then, the rapacious credit card industry may actually be a factor that helps finally tip the scale to motivate restaurant workers to demand fair compensation for their labor.

And there is plenty of profit to be shared. To given one among many prominent examples, Business Insider calculated that, McDonald’s could double the wages of all its restaurant employees for approximately $3 billion. And while $3 billion sounds like a lot of money, “This would knock its operating profit down to a still healthy $5.5 billion.” Presumably, the reason MacDonald’s doesn’t make this choice is the theory of “profit maximization”:

that McDonald’s shouldn’t pay its employees a penny more than it absolutely has to.… McDonald’s should pay those people as little as possible and deliver as much profit as possible to its shareholders. The only purpose of a company, after all, is to make money for its shareholders.

The ethical error here is the evisceration of the common good that results from a greedy, single-minded focus on a bottom line of profit alone. Instead, we need a “triple bottom line of “people, planet, and profit.” Profit motive is still a part of the equation, but it must be balanced with how we treat our fellow human beings and this one planet.

Ultimately, of course, restaurant justice is connected to the larger historic Labor Movement. These days, any mention of worker’s rights is libel to invoke a charge of class warfare, but as that highly successful capitalist Warren Buffet said a few years ago, “There is class warfare, all right. But it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.” And as bumper sticker philosophy tells us, “The Labor Movement: from the folks who brought you the weekend.” Or, “If you like the 40-hour workweek, thank a union member.”

I encourage you to visit the ROC-United website (http://rocunited.org/) if you are curious to learn more about the growing grassroots movement for restaurant worker justice. And I encourage you to explore the connections between that struggle and the larger movement we are seeing forincreasing the minimum wage to be more of a Living Wage. For instance, in my home state, just last week there was a front page article in my local paper about Gov. Martin O’Malley announcing that, “he will focus on raising the state’s minimum wage during his last full legislative session as Maryland’s governor.” As with last year’s focus on legalizing same-sex marriage and the DREAM Act in Maryland (and many other states), I share a hope with many of you and many of my colleagues that once again progressive religious and secular groups will join together to demonstrate that there is grassroots, popular support for greater social, economic, and environmental justice in our country. May it be so. And may we do all we can to support the work of justice.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles