Lent (the forty-day period of preparation for Easter Sunday) has a bad reputation in some quarters as solely negative and dour time. However, the season of Lent is not only a challenge to give up a bad habit (to loosen attachment to the aspects of our lives that unduly occupy our attention), but also an invitation to take on a spiritual practice to refocus ourselves on something positive and healthy.

You might take time each day of Lent to:

- slowly and contemplatively read from a sacred scripture,

- take care of your body by exercising, practicing yoga, or Tai Chi,

- declutter by donating one or more items in your house daily to charity, or

- engage in any of the traditional acts of mercy: feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, welcoming the stranger, clothing the naked, caring for the sick, and visiting the imprisoned.

Lent can be just as much about experimenting with forty days of taking on positive, healthy practices as spending forty days of self-mortification or self-denial.

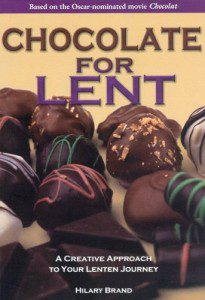

Along these lines, on this Ash Wednesday — less than a week since Valentine’s Day — I invite you to reflect on what it might meant to celebrate “Chocolate for Lent,” a notion I borrow from Roman Catholic Bible study based on the film Chocolat starring Juliette Binoche?

to reflect on what it might meant to celebrate “Chocolate for Lent,” a notion I borrow from Roman Catholic Bible study based on the film Chocolat starring Juliette Binoche?

In the film, Binoche plays a mysterious stranger, who in the mid-twentieth century moves into a small, repressed, religiously-conservative French town and opens a chocolaterie (a chocolate shop filled with an abundance of gourmet sweets) at the beginning of Lent, a time that the town’s traditional mayor feels should be for austerity and abstinence. Adding to the scandal, Binoche’s character has a young child (but has never been married) and is not interested in attending the town’s church.

Now I promise not to spoil all of the plot for those who haven’t seen it. But one twist includes a band of gypsies (or better, Romani people) visiting the town, including one played by Johnny Depp. Suffice it to say that the conflict with the more conservative townspeople heats up further when a relationship develops between the unmarried chocolate shop owner and the visiting Romani — and all during Lent!

Even without giving you all the details, you can perhaps guess that the female chocolatier is the persecuted Christ-figure in this film, whose kindness, generosity, and compassion transform the lives of the townspeople much more that Lent than the harsh severity and self-denial of past Lenten seasons ever had.

According to the author of Chocolate for Lent, the film Chocolat is about more than “Lent versus Chocolate,” “self-denial versus self-indulgence,” or “traditional Christianity versus vaguely spiritual remedies.” Rather, at a deeper level, “this movie is about control” (31).

And although I encourage you to see (or revisit) the film yourself, for now I will share with you just one scene toward the end. There is a delicious moment when the mayor of the town — who has been the leader of the opposition against Binoche’s chocolaterie and who has been practicing extreme self-denial and fasting during Lent — breaks into her chocolate shop on the Saturday before Easter with a plan to destroy all the delicious confections she has made to share with the town for Easter. The mayor’s concern is that her sweets will distract people from what he thinks is the proper way to commemorate Easter through solemn ceremony and traditional theology. Instead, after repressing his hunger for many weeks during Lent, when he goes to destroy her chocolates and accidentally tastes just the smallest amount, he ends up gorging himself.

And although I encourage you to see (or revisit) the film yourself, for now I will share with you just one scene toward the end. There is a delicious moment when the mayor of the town — who has been the leader of the opposition against Binoche’s chocolaterie and who has been practicing extreme self-denial and fasting during Lent — breaks into her chocolate shop on the Saturday before Easter with a plan to destroy all the delicious confections she has made to share with the town for Easter. The mayor’s concern is that her sweets will distract people from what he thinks is the proper way to commemorate Easter through solemn ceremony and traditional theology. Instead, after repressing his hunger for many weeks during Lent, when he goes to destroy her chocolates and accidentally tastes just the smallest amount, he ends up gorging himself.

I won’t spoil what happens when he is discovered Easter morning passed out in the window display of the chocolaterie covered in chocolate. But I will move toward my conclusion with one passage of the Easter sermon the priest of that small town preached in the wake of witnessing this weeks-long battle among his parishioners about the meaning of Christianity, Lent, and Easter. He said on that fateful Easter Sunday,

I’m not sure what the theme of my homily today ought to be. Do I want to speak of the miracle of Our Lord’s divine transformation? Not really, no. I don’t want to talk about his divinity. I’d rather talk about his humanity…how he lived His life, here on Earth. His kindness, his tolerance. Listen, here’s what I think. I think that we can’t go around measuring our goodness by what we don’t do, by what we deny ourselves, what we resist, and whom we exclude. I think we’ve got to measure goodness by what we embrace, what we create and whom we include.

This Lent and beyond, may we be known not for what we deny ourselves, what we resist, and whom we exclude.

May we be known for what we embrace, what we create, and whom we include.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles