There is a fascinating passage from President Obama’s Second Inaugural Address that has stuck with me since I first heard him deliver it. On that cold January day in 2013 (which in a beautiful synchronicity also happened to be Martin Luther King Jr. Day), President Obama said: “We, the people, declare today that the most evident of truths—that all of us are created equal—is the star that guides us still; just as it guided our forebears through Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall….” With that memorable phrasing, our nation’s first black President inscribed into the annals of American history the formulation “Seneca Falls, Selma, Stonewall.”

That alliterative allusion points to an overlapping series of social justice movements in our country. Regarding the significance of these particular references, Dr. Melissa Harris-Perry, an African-American political scientist, pundit, and Unitarian Universalist, said: “When the president name-checked the watershed moments of the women’s rights, civil rights, and LGBTQ+ equality movements, he offered a powerful moment of official recognition”:

- Seneca Falls is a city in New York that was the site of an important early women’s-rights convention in 1848.

- Selma is a city in Alabama that was the beginning point of three protest marches in 1965 for African-American voting rights in which the nonviolent marchers were met with violent, brutal, and bloody opposition.

- Stonewall was a Greenwich Village bar in New York City, where in 1969, members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender community rose up against the injustice of discriminatory police raids and launched the modern fight for LGBT rights in the U.S.

Again, in President Obama’s words: “We, the people, declare today that the most evident of truths—that all of us are created equal—is the star that guides us still; just as it guided our forebears through Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall.”

It matters which stories we choose to tell. It matters that a U.S. president chose to highlight and connect struggles for gender equality, racial justice, and LGBTQ+ rights. And learning to better tell the stories of Seneca Falls, Selma, and Stonewall as part of fulfilling the promises set forth in the Declaration of Independence amplifies the power of this vital narrative. These and other such social justice stories can shape us, our society, and the world we hope to create for future generations: a world of peace, liberty, and justice—not merely for some—but for all.

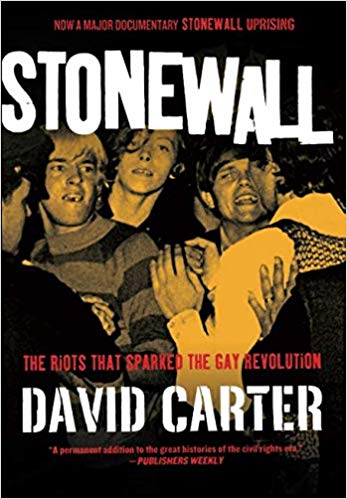

Since we are approaching the 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, I would like to invite us to spend a few minutes reflecting on that particular historic event—to learn to tell that part of our nation’s story better and more robustly—as well as to explore some of its reverberations within our own Unitarian Universalist movement. I will use as our guides Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution by David Carter (St. Martin’s Press, 2010) and Knocking on Heaven’s Door: American Religion in the Age of Counterculture by Mark Oppenheimer (Yale University Press, 2003).

Since we are approaching the 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, I would like to invite us to spend a few minutes reflecting on that particular historic event—to learn to tell that part of our nation’s story better and more robustly—as well as to explore some of its reverberations within our own Unitarian Universalist movement. I will use as our guides Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution by David Carter (St. Martin’s Press, 2010) and Knocking on Heaven’s Door: American Religion in the Age of Counterculture by Mark Oppenheimer (Yale University Press, 2003).

To appreciate the significance of Stonewall, it helps to keep in mind some of what it was like to be a Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, or Transgender citizen of this country at that time. In the summer of 1969:

- Homosexual sex was illegal in every state but Illinois.

- Not one law—federal, state, or local—protected gay men or lesbians from being fired or denied housing.

- There were no openly LGBT politicians.

- No television show had any identifiably LGBT characters.

- When Hollywood made a film with a major homosexual character, the character was either killed or killed themselves.

- There were no openly LGBT police officers, public school teachers, doctors, or lawyers.

- And no political party had a gay caucus. (Carter 1-2)

That was the background against which ordinary LGBTQ+ folks, in response to yet another insulting and harassing police raid on a gay bar, reached their limit and rose up.

The Stonewall Inn at 53 Christopher St in New York City had previously been a restaurant, which closed after a fire. The son of a New York mafia boss bought it, slapped a coat of black paint on the burned wood, and reopened it as a gay club in 1967, two years before the uprising (67). The mafiosos who owned the bar were extremely socially conservative. In words of one Stonewall employee: “They liked our money and hated our guts” (78).

It was not a great setup for many reasons, but in the late 1960s, there were very few options for LGBTQ+ socializing. And although the entrance of the Stonewall Inn was run like a speakeasy during Prohibition—and even though the mafia paid off the police—the police still raided illegal bars like the Stonewall on “an average of once a month” (69, 82). The payoff money did not prevent raids. What it did usually buy was two things: one, advanced notice that a raid was going to happen (so there would be less money and liquor on the premises to be confiscated), and two, the raids were conducted during less busy times—on weekdays or before midnight on weekends.

Part of why that night—Saturday, June 28, 1969—was different is that it was election season and politicians were trying to show they were “tough on crime.” So the police raided the Stonewall Inn at 1:00 a.m. on a summer Saturday morning. That meant there was a large crowd of customers present (143). It was also “the last in a series of raids on gay bars, all in the same neighborhood; and it was the second raid that week on the Stonewall Inn” (257).

There is a lot to say about the Stonewall Uprising, which played out over a series of days, but I’ll limit myself for now to sharing a few vignettes:

The first hostile act outside the club occurred when a police officer shoved a [cross-dresser], who turned and struck the officer over the head with her purse. The cop clubbed her, and a wave of anger passed through the crowd, which immediately showered the police with boos and catcalls, followed by a cry to turn the paddy wagon over…. In the words of one eyewitness, “The cops, used to the cringing and disorganization of gay crowds, snorted off. But the crowd didn’t disperse.” (148)

In fact, the opposite happened: in a fascinating sign of a time before cell phones, the crowd began to grow as people ran to the nearest pay phones to call their friends, urging them to rush over to the Stonewall (149).

In the meantime:

The next bar patron to be taken from the Stonewall was a lesbian… There were three or four policemen on her. She fought them all the way from the Stonewall Inn’s entrance to the back door of a waiting police car. Once inside the car, she slid back out and battled the police all the way to the Stonewall Inn’s entrance…. That struggle…lasted between five and ten minutes…before she yelled, “Why don’t you guys do something.”…. That “set the whole crowd wild—berserk!” That was the turning point…. (151)

And the Stonewall Uprisings have gone down in history “as the first time that thousands of LGBTQ+ folk went out into the streets to protest” for equal treatment under the law (195).

The next year, on the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March was held (253). And on Sunday, June 30, 2019 there will be a massive international pride march in New York City to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall Uprisings. And although there is much work yet to do to achieve full equality for LGBTQ+ citizens of this country—as well as globally—we are raised up on the shoulders of those participants in the Stonewall Uprisings fifty years ago, who helped catalyze the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement.

I also wanted to say a few words about the history of LGBTQ+ rights within my own chosen tradition of Unitarian Universalism. And although there is generally much to be proud of, it is not all good news. Consider that in 1967, the year the Stonewall Inn reopened—two years before the uprising—the Unitarian Universalist Association took a survey of UUs showing that 80 percent of UUs at that time believed that homosexuality “should be discouraged by education” (Oppenheimer 267). But change was about to come.

In July 1970, a year after the Stonewall Uprising, delegates at the UU General Assembly passed a resolution declaring that:

a growing number of authorities on the subject now see homosexuality as an inevitable sociological phenomenon and not as a mental illness [and that] there are Unitarian Universalists, clergy and laity, who are homosexuals or bisexuals…and all peoples [are urged] immediately to bring an end to…all discrimination against homosexuals, homosexuality, bisexuals, and bisexuality” (39).

And although words on a piece of paper did not end discrimination against LGBTQ+ folks within UU congregations, it was a significant move in the right direction.

Fast-forwarding a year to the week before the next year’s UU General Assembly, an ad in the UU World, the associational journal, asked, “Are you a Gay UU?…. If you’re gay, we want to hear from you.” At that 1971 General Assembly, two UU ministers wore buttons that said, “I am gay, how about you?” And they stood in front of a large sign that said, “Gay is groovy,” and passed out “posters, fliers, cartoons, and pamphlets.” By the end of the week, the UU Gay Caucus had grown from the two of them to fourteen members” (42).

1971 was also the year that the UUA released About Your Sexuality, “the first sex education program to affirm that gay sex was natural and should not be criminalized” (50). We still have that curriculum, known today as Our Whole Lives, which is widely regarded as a gold standard in lifespan sexuality education.

Another year later at the 1973 UU General Assembly, the UU Gay Caucus had grown from 14 members to 250, and two-thirds of the delegates voted to create the unfortunately named UUA “Office of Gay Affairs,” which was soon changed to the “Office of Gay Concerns” (54-58). This decision was quite progressive at the time since it was not until a few month later in December 1973 that the “American Psychiatric Association deleted the entry for homosexuality from its diagnostic manual.”

It was not until 1980 that two openly gay men were called to two different UU pulpits. The first two openly lesbian UU ministers were called in 1984 and 1985 respectively. Regarding the significance of those calls, keep in mind that it was the next year, 1986, when the Supreme Court ruling of “Bowers v. Hardwick” upheld the constitutionally of state laws criminalizing homosexual acts—even in private between consenting adults. That case was the law of the land until 2003. And I’ll conclude with a brief story about that Supreme Court decision.

On June 26, 2003 (which ironically was two days before the 34th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising), I was in Charlotte, North Carolina attending a religion conference. As I was preparing to leave my hotel room, I turned on the news and heard the Supreme Court’s ruling in Lawrence v. Texas. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for a 6–3 majority, had struck down the sodomy law in Texas and, by extension, invalidated sodomy laws in thirteen other states. One reason that that news stopped me in my tracks is I had just spent the past three years attending seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, and serving as the graduate assistant all three years for that divinity school’s first out, gay professor—who experienced significant amounts of discrimination during that time. So I was stunned to learn the news that the highest court in the land had just made same-sex sexual activity legal.

As I made my way downstairs, I noticed on the TV in the hotel lobby that Strom Thurmond had died. That news was also stunning. I spent the first 22 years of my life in South Carolina. And for all 22 of those years, Thurmond was my senator. Indeed, he left office six months before his death as the only senator to reach the age of 100 while still in office.

As you may know, Thurmond ran for president in 1948 as the states rights’ Dixiecrat candidate. And in opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1957, he conducted the longest filibuster ever by a lone senator, at 24 hours and 18 minutes in length, nonstop. And although I will not try to delve deeply into the psychological motivations behind Senator Thurmond’s consistent support for racist and white supremacist legislation, I will note that six months after Thurmond’s death, the news broke that when was he was 22, he had fathered a child with his family’s 16-year-old African-American maid. Although Thurmond never publicly acknowledged his daughter, he paid for her education at a historically black college and passed other money to her for some time.

Even without knowing that final twist, I still remember the exact words that went through my mind that morning: “Wow. The world can change. You can have legal gay sex in Texas, and Strom Thurmond is dead.” (I should add, as we say in South Carolina, “Bless his heart.”) Reading the historical records, it is clear that similar sentiments passed through the minds of many people fifty years ago upon learning the news of the Stonewall Uprisings: Wow. The world can change. We don’t have to passively accept discrimination. Together we can work to build the world we dream about—and to turn dreams into deeds.

There is much work to be done—both to advance the cause of liberty and equality as well as to resist those who would roll back the tide of progress—but we are lifted up on the shoulders of many courageous forebears who have come before us in acting for peace and justice. And I’m grateful to be on this journey with so many of you.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles