This past Monday was Labor Day. In addition to enjoying a three-day weekend, it is important to be mindful that Labor Day is about much more than a last bit of time off at the symbolic end of summer. The first Monday in September is also an invitation to remember and celebrate the labor movement’s role in securing workers’ rights in this country. In the late nineteenth century, an increasing number of states officially recognized Labor Day as a holiday, culminating in Congress declaring Labor Day a federal holiday in 1894.

It can be easy to forget how much we owe organized labor. As one bumper sticker says, “Support Unions: from the folks who brought you the weekend, child labor laws, overtime pay, minimum wage, injury protection, workers compensation insurance, pension security, sick leave, safer working conditions, and more!” Historically, many people used to spend 12 (or more) hours/day working for six (or seven) days/week. But “in the early nineteenth century and continuing for over a hundred years, working hours in America were gradually reduced—cut in half according to most accounts” (Honnicutt vii). The labor movement pushed back against the exploitation of workers.

And here is another oft-forgotten twist. In the late nineteenth century, extrapolating from the successes of the labor movement, many of the best economists “regularly predicted that, well before the twentieth century ended, a Golden Age of Leisure would arrive, when no one would have to work more than two hours a day” (vii). For those forced to earn a living through alienated labor, working only two hours a day (for a total of ten hours/week) would mean having time to pursue the American Dream of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” instead of returning home from work too exhausted to do anything but rest briefly before dragging oneself back out to work the next day.

Labor activists did help secure a five-day workweek — and in some industries even a six-hour workday. But starting with the Great Depression in the 1930s, the trend of shortened work hours reversed. A new emphasis arose on growing the economy through perpetually increasing consumer demand. So, many of us find ourselves working increasingly long hours, with less free time to enjoy the fruits of our labors.

So on this week after Labor Day Weekend, I would like to invite us to reflect on the state of work today, to take a quick tour through the history of work, and finally, to bring those two pieces together to use as a springboard to imagine how we might work differently in the future.

Let’s begin with the state of work today. There’s a lot to say, so I will limit myself to two important examples: extreme workers and essential workers.

“Extreme jobs” is a technical term sometimes used by scholars to describe people who choose to work 70 or more hours a week because they love their work, and/or because they are compensated at an incredibly lucrative level. And that number is merely the lower end of the threshold. Some extreme jobs average 120 hours/week. That leaves workers fewer than seven hours per day for everything else, including sleeping, eating, and time with family and community (Hewlett and Luce). And studies show that, “By and large, extreme professionals don’t feel exploited; they feel exalted…. Many people love the intellectual challenge and the thrill of achieving something big. Others are turned on by their oversized compensation packages, brilliant colleagues, and the recognition and respect that come with the territory” (ibid.).

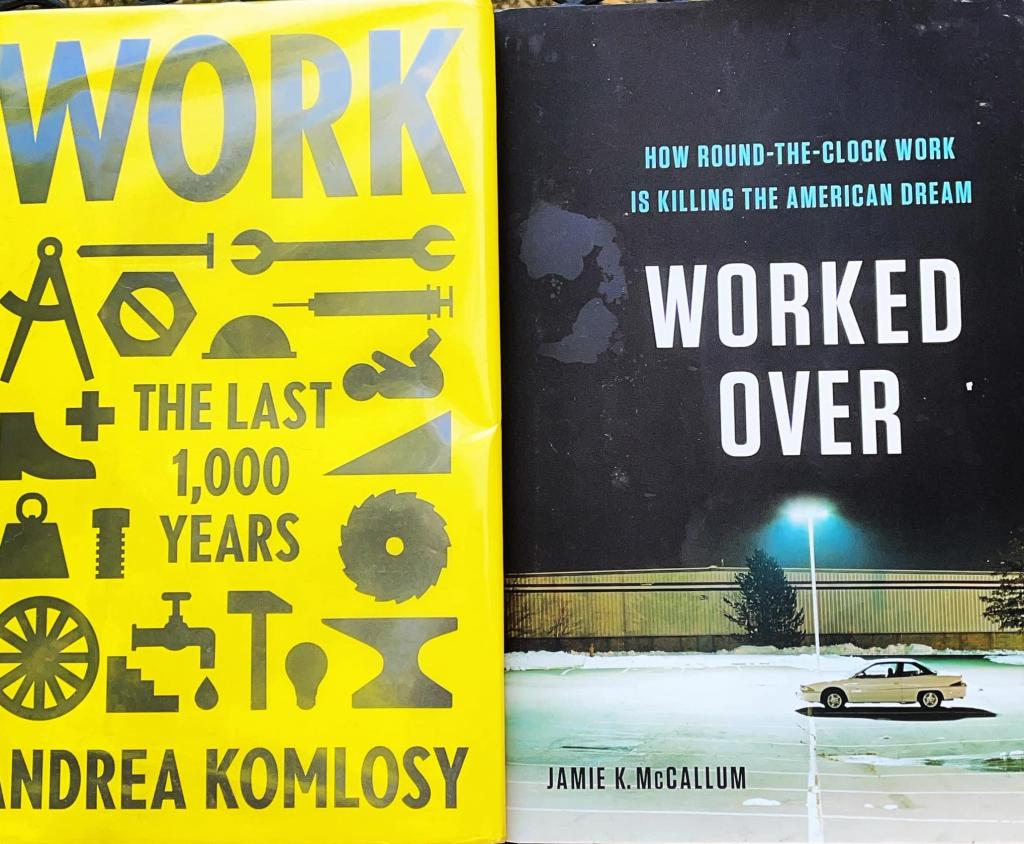

I suspect few of us are extreme workers. If you are, you probably wouldn’t have time to be reading this post. And although some people are doing extreme work mostly for the money, I have brought up the phenomenon of extreme workers because it can serve as a useful case study for an important question. As Jamie McCallum has asked in his recent book Worked Over: How Round-the-Clock Work Is Killing the American Dream: if you are fortunate enough to have a job that you love and find meaningful, is doing more of that work always better (7)?

Even if you love your job, there are other priorities in life. To quote another slogan from the Labor Movement, in the late nineteenth century, there was an organized campaign for the eight-hour work day: “eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will” (24). Combined with the weekend, that’s how we got the forty-hour workweek: eight hours for work, five days per week—but also eight hours of rest every day, eight hours of free time every day, and the whole weekend for rest and freedom. But today, technological innovations have meant that fewer of us are able to clock out after eight hours. Instead, emails, texts, and social media have resulted in work that increasingly suffuses every day, no matter where we are. And it is often difficult to fully unplug oneself even on vacation.

So on one side of the spectrum, we have extreme workers, logging long hours because they love work and/or are incredibly well-compensated.

On the other side of the spectrum are so-called “essential workers.” Although the pandemic has underscored the ways in which essential workers are a key part of our economy, our society too often does not compensate essential workers according to their real value—which makes “essential worker” Orwellian doublespeak that acknowledges the importance of essential work only at a surface level, while being less than transparent about how poorly essential workers are often treated and paid.

And as we juxtapose “extreme workers” and “essential workers,” it’s important to acknowledge that most people around the world do not love their jobs. According to Gallup’s most recent State of the Global Workplace report, “just 15% of employees worldwide are engaged with their jobs. Two-thirds are not engaged, and 18% are actively disengaged.” The situation is slightly better in the United States and Canada, where approximately 30% of people are engaged with their jobs; but that low level of vocational enjoyment is still fairly dismal (Suzman, A Deep History of Work, 387-388).

For many reasons, the current state of work is unjust, both in our country and around the world. And if we look backward, it quickly becomes evident just how much our idea of “work” has changed over time. Since we can be assured that how we work will inevitably change in the future, he key question is, in what direction will it change? Toward more humane work for more people? Or toward more work that primarily advantages only an elite few?

Drawing from Andrea Komlosy’s book Work: The Last 1,000 Years, if we take a quick tour through the history of work, we will find that the modern idea of finding “meaning” through one’s work is decidedly not how the ancient Greeks thought about it. In ancient Greece, the ideal was to be a free citizen who did not have to work, but who rather spent his days divided between lifelong learning and democratic engagement with politics (Komlosy 9-10). When the Roman Empire came to power, the Greeks’ emphasis on community service was eclipsed by an increased focus on the elite having the luxury of doing whatever they individually enjoyed in the private sphere (10). In contrast, with the turn to the Middle Ages, more importance became placed on the Christian work ethic. In this worldview, idleness became viewed as a vice (11) And an even more decisive shift came with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism: “Rather than merely sustaining one’s existence, work was redefined as primarily to create and accumulate capital” (12).

Drawing from Andrea Komlosy’s book Work: The Last 1,000 Years, if we take a quick tour through the history of work, we will find that the modern idea of finding “meaning” through one’s work is decidedly not how the ancient Greeks thought about it. In ancient Greece, the ideal was to be a free citizen who did not have to work, but who rather spent his days divided between lifelong learning and democratic engagement with politics (Komlosy 9-10). When the Roman Empire came to power, the Greeks’ emphasis on community service was eclipsed by an increased focus on the elite having the luxury of doing whatever they individually enjoyed in the private sphere (10). In contrast, with the turn to the Middle Ages, more importance became placed on the Christian work ethic. In this worldview, idleness became viewed as a vice (11) And an even more decisive shift came with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism: “Rather than merely sustaining one’s existence, work was redefined as primarily to create and accumulate capital” (12).

My point with this super-quick tour through labor history is that how and why we humans have engaged in work has changed dramatically over time—which raises the question of how we might change it in the future. Let’s start by returning to the situation we explored earlier for extreme workers of 70 to 120 hours/week who often receive extremely high pay.

In many ways it makes sense for people to be well paid for working hard and providing a valuable service; but there’s an important caveat that we seem to have lost touch with as a society: many ethicists would argue that the amount of wealth an elite few are allowed to earn and keep needs to take into account the common good. For instance, do we need some kind of “maximum wage” or “wealth tax” on the upper end of the wealth spectrum, until we ensure that everyone has at least the basic minimum necessary to live a dignified life? This basic minimum is sometimes called a “stable floor for all.”

Today, “American CEOs take home 312 times what their average employees make” (McCallum 16). We’re way out of balance as a society, and it hasn’t always been this way. “In the past forty years, CEO pay soared by an inconceivable 1,070 percent, and productivity increased by 70 percent, but hourly wages of average workers [inched] forward just 12 percent” (29). The vast majority of us are working harder than ever, but the vast preponderance of compensation is going to the top.

Changes are coming. As I’ve explored in previous posts, “Immigrants aren’t coming for your jobs, robots are!” In the coming years, the rise of automation will provide us with an invitation to re-conceive our relationship to work. Will we allow all the profits from automation to flow almost exclusively to the elite few, or will we choose as a society to explore how we might more equitably expand access to the good life?

Whether or not we can reach that nineteenth-century dream of the two-hour workday, can we begin to revitalize a movement toward decreasing work hours per week? Remember that the focus here is not on the 30% of adults in the United States who enjoy their jobs and would feel constrained and unfulfilled if they could only work ten hours/week. I’m talking about securing more free time for the other 70% who are not engaged at work, who are neutral at best or, at worst, actively hate their jobs.

It’s important to keep in mind that that the forty-hour workweek was not inevitable; it was both a massive change and an achievement secured by the labor movement. Remember that historically, most people used to work twelve (or more) hours a day, working for six or seven days a week—so something like 80 hours/week. But over the course of the nineteenth century, we came to have a forty-hour workweek for many people in this country.

Our idea of what should count as a standard work week has changed before, and it can change again. Marx used to say, “The shortening of the working-day is [freedom’s] basic prerequisite” (228). That’s really worth thinking about: what might open up, what might emerge if more of us had more free time?

And let’s be honest that having a huge percentage of people underpaid for jobs they hate has a lot of revolutionary potential embedded in it. To cite just one present manifestation of this dynamic, this Labor Day Weekend finds our country with “10 million job openings, yet more than 8.4 million unemployed are still actively looking for work.” The discrepancy is that, “There’s a big mismatch…between the jobs available and what workers want” (The Washington Post). Years ago, Janice Joplin said it this way: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.”

That being said, I wish I could guarantee that providing people with more free time would necessarily lead to a utopian future of more people using that free time for “making beautiful things, reading beautiful things, or simply contemplating the world with admiration and delight” (Suzman 411).

If we want to increase the likelihood of such a future, we need to dramatically increase our funding of the arts and humanities. But I’m also willing to concede that more free time would also lead to more people playing video games all day. And those of us who have a hangover from the Christian work ethic of the Middle Ages might still be a little worried that, “Idle hands are the devil’s workshop.”

But I invite you to consider that it may be worth exploring the possibilities of just such a future, compared with the alternative of 70% of people being poorly-paid to do work they hate.

As to how we reach that better future, I’ve written previously about ways to revitalize the Labor Movement— such as passing the PRO Act (“Protecting the Right to Organize”), which would strengthen various protections for workers seeking to support unionization, and increasing penalties for employers who retaliate against unionizers. The PRO Act has passed the U.S. House of Representatives, but is currently one of many important pieces of legislation unlikely to pass in the Senate unless there is filibuster reform.

Overall, my hope in the wake of Labor Day Weekend has been to give us some frameworks for reflection. Understanding how much has changed from the past can empower us to imagine how our current relationships with work might also change in the future — so that increasing numbers of us might enjoy less-alienated labor and more free time for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles