The stories we tell matter. And each telling of history—all the varied stories of our human pasts—are invariably biased. No matter how informed, well-intentioned and open the historian, their perspectives are always constrained by their understanding and experience. History is never neutral. All stories, including all histories, are unavoidably told from some particular person’s—or group’s—point of view, a truth too rarely acknowledged, recognized, and even apparent.

The Haitian American anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1949-2012) wrote about this dynamic in his book Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. I’ll share one quote from that book which has stuck with me: “The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots” (xix). I want to invite us to spend a few moments unpacking what that quotation means.

How can the ultimate mark of power be its invisibility? Try thinking about it this way: if a system seems to work to your personal advantage, the particular ways that power flows through that system to you may feel unimportant—to you. Privileged power can feel invisible, easy to take for granted; such power can feel like “just the way things are around here.”

But if a system disadvantages or oppresses you, it’s equally hard not to notice the way its power works against you within that inequitable system. Thus, Trouillot’s ultimate challenge to systems of oppression is to show, by “the exposition of its roots” that the oppressive system has a highly relevant history; the system now is not “just the natural way things always are”; rather, political and cultural systems are consciously or unconsciously designed so as to advantage the interests and agendas of specific favored groups, thus disadvantaging other groups.

Do you know the saying that, “When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression.” That viewpoint is behind much of the current resistance to Critical Race Theory and the 1619 Project. If the way history has often been told entrenches an invisible (to you) system that unfairly advantages you, then revising its history in a more balanced, honest, inclusive way can feel like reverse discrimination. But the loss of privilege is not reverse discrimination; it’s just finally presenting the past more comprehensively and accurately. Including more sides of the story about how the current power systems came to be can raise awareness about all the ways the world might be different in the future, after alternative perspectives are taken into account. “The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.”

Let me give you another example of what more inclusive historical revision looks like in practice out in the world. If you enroll in an African American history course, the point of view is visible right there in the course title. Similarly if you sign up for a class on indigenous history, women’s history, queer history, etc., you expect to receive an an empathetic, evidence-based and comprehensive perspective reflecting the interests and experiences of these groups. There needs to be truth in advertising.

But many courses that present themselves as being as allegedly neutral“histories” might be more accurately called “White, rich, heterosexual, able-bodied male history.” Too often, such biases are left invisible whether from the instructor’s lack of cultural awareness, their political biases, or sometimes even their unconscious or conscious malice toward the particular oppressed groups.

Always be sure to notice who gets to decide what stories are told and which stories are left untold? Also notice who benefits from these choices. And who loses out? As you’ve heard me quote before: “If you are not at the table, you might be on the menu!” When the stories of our pasts are told, it matters who is in the room where it happens when such decisions are made. Remember the title of Trouillot’s book: Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History.

History has generally been written by the “winners” of conflicts. When two cultures clash, the loser is sometimes obliterated, leaving the winner to write histories glorifying their own causes and methods, even while disparaging the conquered foe. In his book, 1984, George Orwell reminded us that who controls the present gets to control the past—and who controls the past controls the future!

Too often, vital parts of the past have been silenced. Critical Race Theory, the 1619 Project, and other similar endeavors are challenging us as a society to be more honest, open, and inclusive in why and how we have chosen—and will choose—to tell stories of our pasts. In presenting history more equitably, we open up the possibility of a future in which we all come to recognize and support the inherent worth and dignity of every person— a stepping stone to achieving the Unitarian Universalist Sixth Principle, “the goal of world community with peace, liberty and justice for all.”

A turning point in my own understanding of what creating more truly representative histories offers to all of us came about two decades ago when I read Howard Zinn’s The People’s History of the United States, a book which tells “America’s story from the point of view — and in the words of — America’s women, factory workers, African Americans, Native Americans, working poor, and immigrant laborers.”

For now, I’ll limit myself to just one example of this personal paradigm shift. Growing up as a white male in South Carolina, I knew only one story about the Fourth of July—a glorious celebration of American Independence from colonization, as well as a day of cookouts, family, and fireworks. And as with so many things in life, all that is true; but it’s only a partial truth. It’s not the whole story.

Consider these words from Frederick Douglass (c. 1817-1895), who escaped from enslavement here in Maryland to become one of our greatest social reformers and statesmen. A little less than a decade before the Civil War, Douglass delivered one of his most famous speeches, titled “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” I invite you to hear just one paragraph, although the whole speech is very much worthy of rereading in full:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him,

your celebration is a sham;

your boasted liberty, an unholy license;

your national greatness, swelling vanity;

your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless;

your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence;

your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery;

your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parades, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

Douglass was calling out the tremendous dissonance of celebrating July 4th as the anniversary of freedom, liberty, and independence in a country in which millions of human beings were, at that very moment, enslaved—denied their inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

And lest we too quickly dismiss Douglass’s harsh criticism as a long-ago problem of the nineteenth century, let us remember the hard truths that Michelle Alexander outlined in her powerful book The New Jim Crow about our racially biased Prison-Industrial Complex: “Today there are more African American adults under correctional control — in prison or jail, on probation or parole — than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began.” If you don’t have time to read that book, take 90 minutes to watch Ava DuVernay’s powerful documentary 13th on Netflix.

We might also ask: what to an indigenous person is the 4th of July? July 4th celebrates both decolonization—the original colonies declaring their independence from Britain—even while simultaneously celebrating the outright colonization of land already occupied by indigenous tribal nations.

These are hard truths to hear. But as James Baldwin said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed unless it is faced” (Hannah-Jones 122). The stories we tell matter, and it is vitally important to get more skilled and more fluent at telling more accurate and complete stories of our collective pasts by including the perspectives of historically marginalized groups.

One tool for doing this is the ReVisioning American History series published by the Unitarian Universalist Association’s Beacon Press. And over the past few years, I have posted about the first five books in the series:

- A Queer History of the United States (2014)

- A Disability History of the United States (2015)

- An Indigenous History of the United States (2015)

- An African American and Latinx History of the United States (2020)

- A Black Women’s History of the United States (2021)

A seventh book in the series is due to be published soon (Asian American Histories of the United States), so I look forward to sharing about that book with you, likely in May 2023, during Asian American History Month.

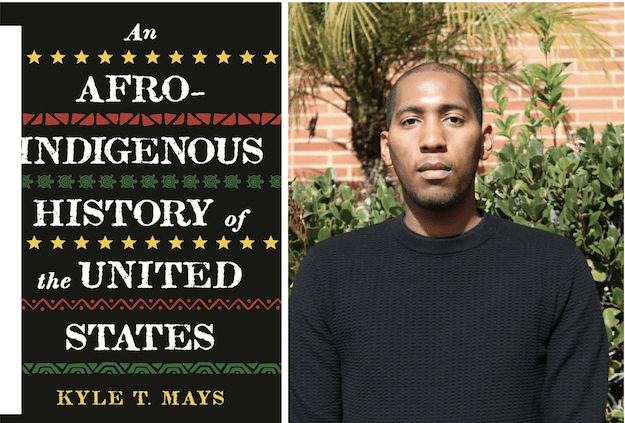

For now, since it is Black History Month, I would like to share with you some highlights from the latest book in this series, An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States by Kyle Mays, a history professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. I found this book to be particularly interesting because Mays seeks to retell American history, not from either an African-American or an indigenous perspective, but from a both/and Afro-Indigenous perspective. As we seek a way forward to collective liberation—in which we all get free—this ability to weave together pluralistic perspectives will be essential.

For now, since it is Black History Month, I would like to share with you some highlights from the latest book in this series, An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States by Kyle Mays, a history professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. I found this book to be particularly interesting because Mays seeks to retell American history, not from either an African-American or an indigenous perspective, but from a both/and Afro-Indigenous perspective. As we seek a way forward to collective liberation—in which we all get free—this ability to weave together pluralistic perspectives will be essential.

Mays’s interest in exploring U.S. history from an Afro-indigenous point of view is an embodied one. His mother is a Black American, “a descendant of enslaved people from South Carolina on her father’s side.” And his father is Afro-Indigenous, with both Black and Saginaw Anishinaabe ancestry (x).

When Mays took courses in Black history, he would find himself noticing what was missing from an Indigenous perspective—and vice-versa—because his indigenous history courses were missing important elements from a Black perspective. Or worse, he would periodically hear his fellow students or professors fixating on instances of anti-blackness among indigenous students: “See, Black people can be racist, too,” or anti-Indigenous sentiments among Black students: “See, those Indians are racist too! They owned slaves!” (76).

Is it true that some people who are Cherokee enslaved some African people? Yes. Conversely, were there so-called “Buffalo Soldiers”—African Americans who fought in the U.S. Army against indigenous people in the West? Yes, that also happened. But too often, these worst examples are the only stories people know about Afro-indigenous history—stories which further divide us, fuel resentment, and burn bridges instead of building them across our differences (xv-xvi).

Now, don’t get me wrong. All these painful truths are parts of the same story of suffering on multiples sides. They need to be told, not covered up. At the same time, we must recognize that they are only partial truths. They aren’t the full story.

Mays grew tired of history told only from the points of view of scarcity and competing oppressions. The “Oppression Olympics,” endlessly debating whose historic oppression was worse, is a losing game for all of us. As an Afro-indigenous person, Mays found himself longing for a written history that also told about all the times Black people and indigenous people have been in solidarity (33). He is seeking to weave together multiple perspectives, and to plant seeds that might grow into and inspire future coalitions for collective liberation.

Although I can’t summarize two hundred pages of history in this post, let me share a few highlights that stood out to me from May’s Afro-Indigenous History of the U.S.

The first example is about Booker T. Washington (1856-1915), born into enslavement in Virginia and freed at age nine through the Emancipation Proclamation. Washington is best known for his efforts to get access to education for Black people. But he was also an important advocate for indigenous people’s rights. Working at the Hampton Institute, Washington witnessed firsthand that forcing indigenous people to assimilate into white culture was harmful and counterproductive. He raised awareness that indigenous people thrived when given access to quality education—without being forced to cut their hair, abandon traditional clothing, or stop using tobacco in their sacred rituals (51). This chapter in Booker T. Washington’s story is a beautiful example of Afro-Indigenous solidarity.

Similarly, I was fascinated to learn that W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963), the first African American to earn a doctorate at Harvard and one of the founders of NAACP, was also an associate member of the American Indian Association (59). Du Bois wanted to publicly signal his support for both Black liberation and indigenous people’s rights.

There are lots of what Mays calls “micro-moments”— little flashes of Afro-indigenous solidarity. The Black American poet Langston Hughes (1901-1967) wrote about the time the Lumbee Indians ran a group of KKK members out of North Carolina (78-9). Or about the times that Black luminaries like James Baldwin and Fannie Lou Hamer spoke not only about the historic oppressions of Black people, but also about the ongoing dispossession of indigenous people from their lands (81, 90).

From indigenous perspectives, there have been important ways that the red power movement was inspired and emboldened by the Black power movement (109-110), just as the Black Lives Matter movement inspired the Native Lives Matter movement. Even more importantly, there are many examples of Black and indigenous people showing up for one another.

For example, in 1972, when indigenous activists took over the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Black activist Stokely Carmichael (1941 -1998) showed up on Day Three of the occupation and said publicly—as the leader of the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party—that “[We] support this movement 100 percent…. This land is their land…we have agreed to do whatever we can to provide help” (112). Carmichael was also present a year later at the Wounded Knee Occupation. In turn, indigenous people were an important part of Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign (118-121).

And just this past year, there was landmark news that the Cherokee Nation removed the phrase “by blood” from many of its laws to “formally acknowledge that the descendants of Black people once enslaved by the tribe — known as the Cherokee Freedmen — have the right to tribal citizenship, which means they are eligible to run for tribal office and access resources such as tribal health care” (CNN). So, yes, we need to acknowledge the painful stories of the past, but we also need to tell the inspiring stories of solidarity and of seeking to repair past harms—to motivate our ongoing work of anti-racism, decolonization, and collective liberation.

If you are looking for a contemporary example of this sort of “fusion politics,” I encourage you to look into the leadership of The Rev. Dr. William Barber through the revitalized Poor People’s Campaign. In particular, this group is planning a Mass March on Washington on Saturday, June 18, which you will be hearing more about in the coming months.

This upcoming action is a reminder that as important as it is to learn to tell the stories of our past in a more honest and pluralistic way, it is even more important to act here in the present to help make the history we want future generations to inherit.

Along those lines, it is important to be aware that Black History Month is about a lot more than one month per year. As Bernice King, the youngest child of Dr. King and Coretta Scott King, has said, “We celebrate [Black history] all year. February is just our anniversary.” Moreover, Black History Month is not only about Black pasts, but also about Black futures. It’s about remembering our pasts more fully and inclusively, so that together we might co-create a better future for all.

The Black activist and scholar Angela Davis (1944-) says it this way: “Movements…are most powerful when they begin to affect the vision and perspective of those who do not necessarily associate themselves with those movements” (172). Reading An Afro-Indigenous History of the U.S. in addition to Beacon Press’s ReVisioning American History series more generally—are one among the many actions available to us for opening our hearts and minds into widening our circles of compassion and deeper solidarity across our differences.

We can tear down the systems of greed, ignorance, and hate that create and sustain generational trauma, and instead, build up systems of wisdom, compassion, and generosity. You deserve—each of you (and all human beings)— deserve loving kindness, peace, dignity, love, safety, and protection. What might that look like in practice? One Afro-indigenous vision for how we can build such a world together is what the Movement for Black Lives calls the Red, Black, and Green New Deal — a way forward deeply invested in indigenous people’s rights, racial justice, climate justice, economic justice, and voting rights to protect our democracy. May we hold all this in our hearts, seeking to discern how, individually and collectively, we might feel led to act for our collective liberation.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles