The last few times Christmas Day fell on a Sunday were 1994, 2005, and 2011. You can mark your calendar for 2022 since it will happen next in six years — and then again in 2033, 2039, 2044, and 2050. In 2050, I realized I would be 72, so I stopped counting there. (I hope to retire at some point!)

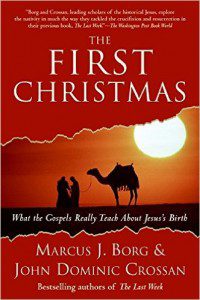

Rewinding the clock back further to the original Christmas Day, we do not actually know the year much less the day on  which Jesus was born. As the historical Jesus scholars Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan remind us in The First Christmas: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’s Birth (HarperOne, 2007), “The date of December 25 was not decided upon until the middle of the 300s. Before then, Christians celebrated his birth at different times —including March, April, May, and November” (172). Birth records were not kept for Jesus or any other peasants born in the backwaters of Galilee more than two thousand years ago. We do, however, have vital records for some aristocrats such as Herod the Great (74/73 BCE – 4 BCE). And if there is any truth to the biblical claim that Herod was the ruler of Judea when Jesus was born, then we know that Jesus was born no later than 4 B.C.E., which is the year Herod died. So Jesus’s birth is often estimated to be sometime during 4-6 B.C.E., the final two years of Herod’s life (147-148).

which Jesus was born. As the historical Jesus scholars Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan remind us in The First Christmas: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’s Birth (HarperOne, 2007), “The date of December 25 was not decided upon until the middle of the 300s. Before then, Christians celebrated his birth at different times —including March, April, May, and November” (172). Birth records were not kept for Jesus or any other peasants born in the backwaters of Galilee more than two thousand years ago. We do, however, have vital records for some aristocrats such as Herod the Great (74/73 BCE – 4 BCE). And if there is any truth to the biblical claim that Herod was the ruler of Judea when Jesus was born, then we know that Jesus was born no later than 4 B.C.E., which is the year Herod died. So Jesus’s birth is often estimated to be sometime during 4-6 B.C.E., the final two years of Herod’s life (147-148).

Theses sorts of “historical-critical” questions related to the Quest for the Historical Jesus fascinate me. But I’m interested not only in whether the stories of Jesus’s birth are factual (the answer is—not so much), but also in the meaning and power of these stories — both then and now. Irrespective of whether all the details actually happened in history, there is often a reason these stories were told and retold — a reason that often has continuing relevance today (Borg and Crossan ix).

If you grew up with Christmas pageants — featuring children as white-robed angels and bathrobe-clad shepherds — then it can be surprising to read the Bible for yourself and discover that almost every Christmas pageant wildly conflates two significantly different versions of Jesus’s birth: one in the first two chapters of the Gospel according to Matthew and the other in the first two chapters of the Gospel according to Luke.

To briefly expand our frame of reference, it is interesting to note that, in contrast to Matthew and Luke who begin their Gospels with Jesus’s birth, the chronologically earlier Gospel of Mark begins with Jesus as an adult. The chronologically later Gospel of John begins before creation: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” So counter-intuitively, the later the text was written chronologically, the farther back — and the more elevated — the claims being made about Jesus. Paul, our earliest written source for the Jesus tradition, writing only 20-30 years after Jesus’ death, mentions Jesus’s birth twice, but does not mention it as exceptional in any way — only that he was “descendent of David” (Romans 1:3) and “born of a woman” (Galatians 4:4). Mark, written approximately forty years after Jesus’s death starts his story with Jesus’ baptism as an adult. Writing approximately ten years after Mark, Matthew and Luke, start the story much earlier with Jesus’s birth. Writing yet another decade-or-so later John starts the story at creation (25-26).

There’s a lot more to say about all that, but for now to return our focus to Christmas, imagine that we were preparing to stage a Christmas pageant that was going to be based either on Matthew’s version exclusively or Luke’s version exclusively. Matthew, for example, is the only Gospel that has the story of Joseph’s dream warning the holy family to flee to Egypt. Matthew is also the only Gospel with magi bringing gifts. (Do you know the trick question about how many magi there were? There are three gifts; the number of magi are unknown. We only know there is more than one — because we are told there are magi plural, not a singular magus.)

Also, according to Matthew, Jesus is from Bethlehem, is born in Bethlehem, and relocates to Nazareth to escape Herod. It’s only in Luke that Jesus is from Nazareth, travels to Bethlehem for the census, and then returns to his hometown of Nazareth. Luke is also the only Gospel with shepherds or an angelic annunciation to Mary about Jesus’s miraculous conception. Another interesting distinction is that if you take out the genealogy of Jesus at the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel, his version of Jesus’s birth is only 31 verses — whereas Luke’s version is four times longer, weighing in at 131 verses.

So imagine “Act 1, Scene One” of a Matthew-only Pageant: we would open with Joseph as the main character. There would be “no story of the birth itself, no swaddling clothes, no stable, no manger, no angels singing to shepherds on the night of Jesus’ birth. All of these are from Luke” (5). Scene two would be the story of the Magi following the star and meeting King Herod. Next we’d have the Adoration of Magi presenting the gifts to Jesus, the flight to Egypt to escape Herod, Herod’s Slaughter of the Innocents, and finally the Return to Nazareth (6-8). Overall:

It’s surprising how little of Matthew’s birth story is about Jesus; Jesus is almost “off stage”…. There is no story of his circumcision, no story of him being blessed in the temple as an infant by Simeon and Anna, no story of him later at age twelve in the temple amazing the teachers with his wisdom. All of these are in Luke. Instead, the narrative dynamic of Matthew’s story focuses on Joseph and his dilemma and on Herod and his unsuccessful attempt to destroy Jesus. (9-10)

Conversely, if we were to stage a pageant based solely on Luke, then John the Baptizer’s parents, Zechariah and Elizabeth, would be major roles — as would women generally. Whereas in Matthew, Mary is “a completely passive figure, neither speaking nor receiving any revelation,” in Luke’s version, Mary is a main character and Joseph is “almost invisible” (20). Another distinguishing feature of Luke’s pageant would be music. Luke’s version is the only place we hear the Benedictus (sung by Zechariah), the Magnificat (sung by Mary), the Nunc Dimitis (sung by Simeon), and the heavenly chorus by the angels (21).

There is also a lot to say about the ways both of these birth narratives echo themes from the Hebrew Bible. Although there are many ways these birth narrative are made up, they were not made up out of thin air. Rather, they are a powerful recapitulation of themes from the Jewish Torah and Prophets — a result of reflecting on the life and teachings of Jesus in the context of Jewish oppression by the Roman Empire.

Most explicitly in Matthew, there are multiple ways that Jesus is symbolically presented as the new Moses — such that Herod (and Caesar) are cast as the new Pharaoh. In Exodus 1-2, Pharaoh plots to kill all newborn Jewish males. In Matthew 1-2, the same plot structure happens with Herod. Just as the Torah is traditionally known as the five books of Moses (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, Deuteronomy), it is no coincidence that in Matthew there are five divine dream, five scriptural fulfillments, five major addresses by Jesus (42-46). Similarly, the story of the Magi is inspired directly from the prophet Isaiah 60:6 (183). The larger hope is that Jesus might show a new way of resistance and resilience under the Roman Empire — just as Moses and Joshua had led the people from slavery under Pharaoh — and led them to liberate the Promised Land from the Canaanites many centuries earlier (ix-x).

Today these stories continue to point us to the ways that resistance and resilience can come from the most unlikely places — even in “a child, born in poverty and homelessness and among animals, to parents who would soon flee and become refugees in Egypt” (Rabbi Michael Lerner). And so this Christmas, what new life, what new hope is being be born in your life, in our life, or in the life of the world?

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles