Karl Rahner, one of the most renowned Christian theologians of the twentieth century, once famously remarked that “the Christian of the future will be a mystic or will not exist at all.”

For people whose experience of Christianity is, often, little more than a religion invested in obedience and in patriarchal morality, this seems to be a bold statement. After all, mysticism implies not legalistic religion, but living spirituality — heart-felt intimacy with God, centered on a miraculous and joyful appreciation of the Spirit’s ability to heal and transform lives. Can Christianity and mysticism really co-exist?

Not only can Christianity be a mystical faith, but in fact a mystical element of Christianity has existed since the time of Jesus. But for a variety of historical, social and political reasons, Christian mysticism has always existed on the margins of the church. In the fourth and fifth centuries, as Christianity gradually moved into its position as the dominant religion in the Roman empire, the mystics, contemplatives, and others who sought profound intimate communion with God retreated from the cities into the deserts and the wilderness. These “Desert Fathers and Mothers” were the founders of the first monasteries — intentional communities of people who came together to live in perpetual prayer and meditation. By the middle ages, Christian mystics were, for the most part, found only in the monasteries and convents; then in the sixteenth century, when the Protestant Reformation led to religious strife (and, often, bloodshed), mystical spirituality fell under suspicion by both Catholics and Protestants. Although there have been mystics in every century of the Christian era, the sad reality is that, because of the political nature of the institutional church, many mystics have been persecuted, some even killed, and others learned to camouflage their wisdom teachings in carefully worded books and poems that appeared non-threatening to the religious authorities.

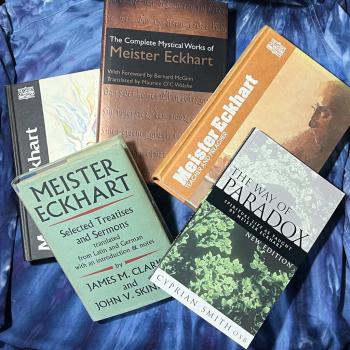

So the mystics (and their teachings) are, in a very real way, Christianity’s best-kept secret. And even though some Christians of the third millennium remain suspicious of mysticism, many others have begun to embrace the transfiguring beauty of such core spiritual practices as meditation, lectio divina (“sacred reading,” a meditative approach to the Bible and other wisdom texts), and contemplative prayer — the profound form of prayer in which meditative silence is offered directly to God for the purpose of seeking and fostering deeper spiritual intimacy and communion. Meanwhile, even familiar Christian practices such as the Catholic Rosary are being rediscovered as tools for entering into contemplative silence; while other, lesser known exercises (such as deeply meditative “prayer of the heart” from Eastern Orthodox Christianity) have gained newfound popularity as means for Christians to embrace unitive (nondual) states of consciousness, where — in the words of one great mystic, Meister Eckhart — “The eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me. My eye and God’s eye is one eye, and one sight, and one knowledge, and one love.”

The roots of Christian mystical wisdom are found in the Bible itself. Unfortunately, centuries of reading and interpreting the Bible according to perspectives that have often been subtly (or explicitly) anti-mystical has made the visionary power of the New Testament’s wisdom teachings far too easy to miss. For example, the first verse of Psalm 65 makes the bluntly contemplative statement “To you, God, silence is praise” in the original Hebrew — but this verse has often been mistranslated when rendered into English or other languages; presumably many scholars who translate the Bible could not wrap their minds around the idea that silence could actually be a means for worship.

But for those who have “eyes to see,” the mystical message of such writings as the Gospel of John or the Letters to the Ephesians can become obvious —just like the 3-D image in a “Magic Eye” poster is hidden at first, but becomes impossible to miss when we learn to look for it in just the right way. From a mystical perspective, “just the right way” means approaching the Bible as a document encoded with messages about what the ancient Greeks called theosis — participation in the very nature of the Divine.

Christianity is built on two controversial—but thoroughly mystical—teachings: first, that Jesus of Nazareth is both fully human and fully divine, and furthermore, that this same Jesus is, literally, one with God, one person in a trinity of persons who share the Divine Unity. For many Christians, these teachings have been interpreted to stress humanity’s separation from Divinity: Christ may be one with God, but no one else is. This, however, is not supported by the mystical wisdom found in the New Testament. Indeed, Jesus proclaims that he is one with God in the Gospel of John (see verse 10:30). But Biblical writings also stress the oneness between Jesus and those who follow his wisdom teachings. “We, who are many, are one body in Christ, and individually members one of another,” proclaims Saint Paul in his letter to the Romans. Christ is one with God, and we are one with Christ. Saint Peter is even more blunt, proclaiming that by the promises of Christ, his followers become “partakers of the divine nature.” Mystically speaking, Christianity points toward Divine communion as the ultimate destiny of being human.

Granted, Christian mystical theology is not the same as other wisdom teachings from around the world. Some wisdom paths point toward union with the Divine as the ultimate truth, suggesting that the experience of being a separate human person is, ultimately, simply an illusion that will fall away when we finally, fully, recognize our oneness with the Sacred. Christianity offers a different approach: in which the distinction between God and humanity is taken at face value, understood not as an illusion but rather as a simple point of fact in how the cosmos is structured. Such a distinction exists, according to Christian mystical teaching, not because humanity is inferior, but rather because it is only in the distinction between Divinity and humanity that we are able to fully, truly and ecstatically love each other. Thus, Christian mysticism celebrates communion with God as the ultimate destiny of humankind: eternal life is a never-ending cosmic dance, in which humanity and Divinity interpenetrate one another, joyfully sharing love and communion like a flower that is forever opening wider and deeper, evolving into ever new dimensions of blissful celebration.

While Christianity has its own distinctive mystical teachings that in some ways mark it as different from other spiritual paths, those who drink deeply from the wells of Christian contemplation tend, like mystics from all paths, to be far more interested in what unites people of different traditions, rather than what separates us. In the history of the Christian mystics, again and again the contemplatives have been the ones who reach out beyond the boundaries of institutional religion to embrace the teachings of other faiths. Clement and Origen, early mystics from the second and third centuries, embraced the wisdom of the pagan Greek philosophers in their teachings. Later, in Ireland and other Celtic lands, the saints of the Christian monasteries integrated druidic teachings and practices into their spiritual observance. In renaissance Spain, a number of Christians incorporated elements of the Kabbalah into their teaching; and the twentieth century was full of visionary Christians who reached out to the spiritual treasures of other cultures and paths: the Benedictine monk Bede Griffiths embraced Vedanta while the Trappist monk Thomas Merton explored Buddhism; Valentin Tomberg integrated Catholicism and Anthroposophy; and Mary Margaret Funk continues the work of deep interfaith encounter as she, a Benedictine nun, engages in constructive dialogue with members of the Muslim faith community. For Christians such as these, devotion to the wisdom teachings of Jesus and his followers is not about religious exclusivity or a belief that Christianity is superior to other faiths; rather it is about a joyful celebration of the beauty, splendor and diversity of all positive paths.

What difference can the mystical element of Christianity make in our world today? Sadly, most Christians remain unfamiliar with the spiritual wisdom hidden in their own tradition. But more and more people, both inside and beyond the institutional church, are turning to classic spiritual disciplines such as meditation, contemplation, lectio divina, regular chanting or recitation of the Psalms and other prayers (known as the Divine Office), devotion to Christ, Mary, and the saints, and turning to monasteries and convents for retreats grounded in silence and under the guidance of monks and nuns who have devoted their entire lives to prayer. The result, of course, is that more and more people are opening themselves up to joyful, visionary, and transfiguring encounters with Christ and the Holy Spirit. More and more Christians are finding in their faith not just the legalistic religion of old, but exciting possibilities of unitive consciousness found through silent communion with God. Such encounters may be thought of as “supernatural” but the case could be made that mystical spirituality is utterly natural: it is something that can reach us in the ordinary moments of life. At the same time, the encounter with God could also be so subtle that it is easily missed. No matter how glorious or humble, extraordinary or ordinary, such moments of communion with God often are marked by a profound sense of Divinely-given love, joy, and peace. They also can lead to a deeper sense of trust in God, love for other human beings, and — most crucial of all for our time — a profound respect for people of other cultures and faiths.

In other words, mystical wisdom and practice is not only the best hope for the future of Christianity, but it can also contribute to something that we all yearn for: a world shaped by peace and harmony among the people of all positive paths.

This article, in a slightly different form, originally appeared in the Summer 2010 issue of Evolve! (volume 9, number 3).

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.

Stay in touch! Connect with Carl McColman on Facebook: