In the introduction to her book Writing the Icon of the Heart, Maggie Ross makes this rather in-your-face claim:

The word ‘mystic’… has, in my view, become entirely useless. It has acquired nuances of romanticism, exoticism and self-absorption. In addition, far too many studies of ‘mysticism’ and ‘spirituality’ are based on a modern and narcissistic notion of ‘experience’ as self-authenticating that corresponds neither to the way the brain works nor to notions of experience in the ancient and medieval worlds, which in fact do correspond to the way the brain works.

She’s not alone. Here’s what William Harmless, author of Mystics, has to say:

If you wander into your local Barnes & Noble or Border’s, you soon discover whole shelves devoted to what booksellers catalog as “mysticism.” There you usually find legitimate books on mysticism mixed in with stuff on the occult and witchcraft, fortune-telling, mind reading, and alien abductions. Mysticism, of course, has nothing to do with such matters, but the confusion on the shelves illustrates how in popular parlance “mysticism” can become a catch-all for religious weirdness. In the 196os it became fashionable to suggest that mystics experienced altered states of consciousness and that such states could be reproduced with drugs or other mind-altering techniques. Much earlier, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, philosophers tended to write off mystics as either gullible cranks or deluded neurotics.

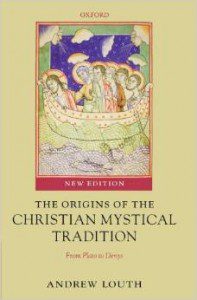

Andrew Louth, in the afterword to the second edition of The Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition, offers a thoughtful argument as to why words like “mystical” and “mysticism” are more trouble then they’re worth: that the words “mystic” and “mystical” as used in the first centuries of Christianity carried a meaning that was embedded in liturgy, the sacraments, and reading of scripture, and only became associated with inner experience or personal awareness of God’s presence in the middle ages, as a kind of subversive reaction the the power of the church and the priesthood. Our much more modern word “mysticism” implies a kind of tradition of experiencing God, but this is a modern projection back on to church history: none of the people we think of as mystics today (John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila, Julian of Norwich, Meister Eckhart and so forth) would have called themselves mystics. They would have had a self-understood identity simply as “Christian” or “Catholic,” followers of Christ seeking to be as faithful as possible according to the religious expectations of their day.

Well, as humbling as it is to admit it (considered that I’ve written three books with some variation of “mystic” in the title and will have another one out in 2016 or 2017), I agree with these three scholars. Yep. Mysticism is a dirty word.

But I’m not willing to go as far as Ross and dismiss the word as “entirely useless.” Like it or not, the words are in our language and plenty of people continue to feel attracted to the concept, and if they are attracted to mysticism for basically experiential or narcissistic reasons, they need to be educated, not denounced. Harmless tries to parse out the difference between “good” and “bad” mysticism (I’m reminded of Glinda asking Dorothy “Are you a good witch or a bad witch?”), and so I think he is taking that more sensible, “let’s educate ourselves” approach. And Louth actually goes a long way toward providing a historical background to help us discern how mysticism is best understood in relation to social or political dynamics within the church, which in turn could shed some light on what it means to be a seeker after God today.

Because that’s the real issue here. I could care less about whether or not I’m a mystic. I want to be a lover of God. I want to respond to God’s love. I began to engage with this concept of “mysticism” and “mystical tradition” after reading authors like Evelyn Underhill or Thomas Merton, who use such terms uncritically — but let’s be clear: what drew me to those authors (and this language) was a hunger for God.

Was that hunger narcissistic, originally? Of course it was!

Anyone who has read Bernard of Clairvaux understands that the quest for God begins in narcissism. So should we condemn narcissism (as Ross appears to be doing), or should we recognize that narcissism is a problem only when people decide to stay put there? I opt for the latter. Granted, in today’s society it’s a huge challenge — we live in a profoundly narcissistic culture, and our many forms of distraction and addiction and obsession with entertainment and consumerism compound the problem. But narcissism isn’g going to go away by talking about how bad it is. The solution to narcissism is to discover pathways out of it, into deeper and more truly satisfying ways of loving: loving ourselves, loving our neighbors (including our enemies) and loving God.

So back to the title of this post. Why is mysticism a dirty word? Well, because it has become so corrupted by being used to mean so many different things. Modifying it as “Christian mysticism” helps some, but again, over two thousand years it is far too easy to project modernist or postmodernist notions about mysticism onto past writers, thereby misunderstanding what they were really trying to say. But perhaps the single most important reason why mysticism is a dirty word is because it can lead us to settle for the idolatry of experience. We say we hunger for “the experience of God.” But which do we want? God? or just the experience of God? Do we just want God to entertain us? Or are we seeking a true glimpse into the nature of eternal and unconditional Love, which will probably scare us from one end of the galaxy to the other and leave us forever changed?

Because I think the bottom line is this: “bad” mysticism is just another addiction, it leaves us hungering for more mysticism, while “good” mysticism points beyond itself to God. “Bad” mysticism reinforces our narcissism, whereas “good” mysticism calls us beyond it. But that “going beyond” feels like dying. And it’s up to us to learn the difference, and never to settle for the “bad” kind of mysticism, no matter how entertaining or “experiential” it might seem to be.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.