In the Celtic lands, you’ll find places with names like Dysart or Dysert. There’s Dysart in Scotland, a suburb of Kirkcaldy, where a Celtic holy man named St. Serf once lived. Or there’s Dysert O’Dea in Co. Clare, Ireland, the site of a monastery said to have bene founded by St. Tola in the eighth century.

Others can be found, sprinkled across the land, often with some sort of connection to a saint or monastery of old.

These places are named for the Gaelic word díseart, which means “hermitage.” It’s an obvious cognate for the English word “desert,” which may seem a little odd, since the Celtic lands tend to be lush and green — Ireland is called the Emerald Isle, not the Sandy Isle!

Although some places in the Celtic world are austere and desolate — for example, the windswept islands of the Hebrides or the Skellis, or the limestone-covered Burren in the west of Ireland which looks like a moonscape here on earth — “desert” is not really a word that leaps to mind when we think of the lands where the Celtic saints lived.

So what’s the story behind these díseart place-names? There are some who say it goes back to the earliest days of Christian spirituality — the spirituality which inspired the great Celtic saints like Patrick and Brigid and Columcille. And perhaps it’s a clue to understanding the roots of Celtic Christianity, roots that help us to see how Celtic wisdom fits in with Christian spirituality as a whole.

Jesus and the Desert

After Jesus was baptized, the Bible tells us that the Holy Spirit drove him into the wilderness — the desert — where he fasted for forty days and forty nights. This led to an otherworldly encounter with the spirit of evil, who proceeded to tempt Jesus in several ways. The evil one encouraged Jesus to assuage his hunger by performing miracles — such as turning stones into bread. Then he tried to goad Jesus into proving his spiritual mastery, by throwing himself off a parapet of the temple, trusting the angels to save him. Finally, the spirit offered Jesus a devil’s bargain: in exchanging for worshipping evil, Jesus would receive earthly power and renown.

Jesus, of course, rejected all these temptations, and went on to begin his ministry of healing and teaching which would culminate in his passion, death and resurrection. But ever since the story of his desert sojourn and temptation in the wilderness was recorded in the gospels, it has fired the imagination of the succeeding generations of Christians.

By the third century, the deserts of Egypt, Palestine and Syria had become a destination for those who wanted to give everything to God. Especially after Christians were no longer persecuted by the civil authorities, withdrawing into the desert — for a life of solitude, prayer, fasting, and facing down the temptations for one’s demons — became the ultimate display of devotion. Instead of the martyrdom of blood, becoming a hermit in the desert became a “living witness” to a life fully surrendered to God.

It was in the deserts of the Middle East where the first Christian monasteries were established. Monasticism quickly spread throughout the Christian world, all the way to the Celtic lands in the northwest of Europe. Christianity took root in the Celtic lands through the cadences of monastic chanting and the simplicity of a communal way of life — a way of life imported from the desolate lands of Egypt and Palestine.

So, one way to unpack the spiritual wisdom of the Celtic saints is to explore the mystical teachings of the Desert fathers and mothers, the holy men and women who retreated into the wilderness in imitation of Jesus — only not just for forty days or so, but for their entire lives.

But is the fact that there are places called díseart sprinkled throughout the Celtic lands enough to establish a link between the Desert Fathers and Mothers and the saints of Ireland, Scotland and Wales?

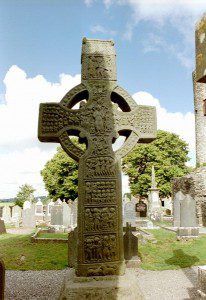

The Clue in the High Cross

The Celts left us another important clue to the esteem with which they held the spirituality of the desert. Of the High Crosses found at monastic sites throughout Ireland and Scotland, many are beautifully carved, with scenes depicting events from the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the lives of Christian saints.

These crosses, which were probably colorfully painted back in the day, served the same kind of function that stained glass served in churches of a later age: as a kind of “picture book” illustrating the key events, and therefore the key beliefs, of the Christian faith.

Scholars have determined that the scene most commonly portrayed on such crosses is, of course, the crucifixion, followed by various other events from the life of Christ. But the most commonly portrayed scene outside of Biblical events on Celtic high crosses is the meeting of Antony of Egypt and Paul of Thebes.

Those names may not be familiar to you, but in the world of Christian monasticism, Antony and Paul are heroes of the faith. They were two of the earliest, and most renowned, of the hermits of the Egyptian desert, both of whom were memorialized in biographies written by their admirers. Indeed, in the Life of Paul of Thebes, written by Saint Jerome (famous for making a great Latin translation of the Bible), the story of the meeting between these two famed hermits is recounted.

It’s a charming story, and very likely more legend than fact. But it depicts two men who have given everything to God, who trust mightily in the Lord for their very sustenance, and who meet one another in a spirit of humility and fraternal charity.

Why would this be the event that would capture the Celtic imagination? Why not the martyrdom of Alban (the first Christian killed for the faith in the British Isles), or the coming of Patrick to Ireland? I think it’s safe to assume that the Celtic saints revered the Desert Fathers and Mothers precisely because of how high a regard with which they held the spirituality of the desert.

So how does Celtic wisdom embody the spirituality of the desert?

Like the Desert Fathers and Mothers, the Celtic saints valued a solitary life of seclusion and contemplation. Some, like St. Kevin, sought to withdraw from the company of others, yearning to find God in the silence of a hermit’s life. Others — again following the patter of the desert Christians — balanced the thirst for solitude with the challenges and joys of communal living.

Like the desert elders, the Celts embraced a life of austere simplicity, marked by regular prayer, fasting, and meditation. The saints of Egypt and Ireland both understood that withdrawing into the solitude of the wilderness meant, sooner or later, wrestling with the sinful nature of one’s own thoughts and temptations. And finally, like the monks of the desert, Celtic Christians understood that the path to holiness was marked by repentance, humility, obedience, and immersion in the scriptures.

It’s easy to romanticize “Celtic Christianity” as a kind of ancient nature mysticism, thanks to the beautiful landscape of so much of northwest Europe as well as the lyrical celebration of God’s creation found in ancient Irish poetry. But it’s important to remember that Celtic wisdom means more than just living in harmony with the natural world (even though that certainly forms a part of it). For the Celtic saints, caring for the good earth was a natural outgrowth of deep devotion to God — if you are going to care for a great work of art, it begins with love for the creator.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.