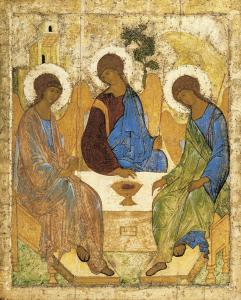

The heart of Christian spirituality is the Mystery of the Holy Trinity.

This is the ancient wisdom teaching that God is one God, in three persons: Father/Creator, Son/Redeemer, and Spirit/Sanctifier.

We call ourselves “Christians” because we follow the 2nd Person of the Trinity: Jesus, the Christ. But it would be just as accurate — some might say even more accurate — to call ourselves Trinitarians, the people of faith in this Triune God.

The Trinity is controversial: Jews and Muslims reject this way of experiencing God, and even among many Christians it remains, well, a mystery (pardon the pun). Cynics dismiss the Trinity as a compromise that early Christians came up with, to reconcile their faith in Christ with their insistence, inherited from Judaism, that God is One.

It is not my goal to argue the philosophical merits of the Trinity — I would much rather refer you to people far more eloquent than I am (like Karl Rahner or Saint Augustine). Rather, I want us to reflect on the spirituality of the Blessed Trinity.

A growing understanding of the Trinity in our time, which has roots going all the way back to the early centuries of the Church, is simply this: The Trinity makes sense because a three-person God is a God whose very nature is love and relationship.

In other words, what matters about the Trinity is not the “threeness” or the “oneness” or even the logical challenges of parsing out God’s nature(s), God’s person(s), God’s oneness, so forth and so on. All of that philosophical posturing really misses the point.

The point is to approach the Trinity from the heart.

We worship a Trinity because God is a God of love, and in the relationships between Yahweh, Yeshua, and Ruach — between the Father, the Christ, and the Holy Spirit — we find the heart of love: the lover, the beloved, and love itself, eternally pouring forth like a joyful dance, from each of the persons, to each of the persons, and through each of the persons.

The Love that Gives Itself Away

And the joy of the love of the Trinity? It doesn’t stop there: God in turn shares that ever-flowing love, lavishly and joyfully, with all of creation.

The Bible teaches that we “mere mortals” are created in the image and likeness of God, which means we are created in the image and likeness of Love: ever capable of being the lover, the beloved, and love itself, and therefore to give ourselves in love to one another. The Bible also teaches that we are the temples of the Holy Spirit, which means all the love that flows from us and to us and in us ultimately has its origin in God.

Furthermore, us mere mortals are called to be the Body of Christ — we participate in Jesus’s ongoing body-ness; indeed, now that Christ has ascended, we are it — we are the Body of Christ, still present on earth. But because we are the body of Christ, we (collectively but also individually) are partakers of the Divine Nature (2 Peter 1:4), which means we dance the very dance of the love of God: by virtue of being baptized into Christ, we are one with Christ, therefore one with God.

In other words, the heart of Christianity — and, therefore, Christian spirituality — is recognizing the gift of Divine Love which has already been given to us, from the God who is Lover/Beloved/Love, and who pours that love to us and through us, to others and therefore to the entirety of creation.

Now, we can also talk about all the ways we resist and reject that gift of love — that gets into the theology of sin, fallenness, the need for repentance, the call to holiness, and so forth. That’s all important stuff — but it also tends to be the kind of stuff that many Christians over-focus on, so I’ll leave that conversation aside for now.

Praying to the Triune God

For now, I want to talk about prayer and the Holy Trinity, and especially contemplative prayer and the Trinity. How do we pray to the God who is Love/Lover/Beloved? How do we contemplate this God, this God who is not elsewhere, who is more present to us than we are to ourselves?

To answer this question, I’d like to propose three ways of thinking about — and encountering — God, right here in our own bodies. These three ways of encountering God correspond to the Three Persons of the Holy Trinity. Remember, these are not three “different” Gods, rather simply three different ways of encountering the Three Persons (the “Three Relators”) of God.

We encounter the Father, the Creator, the God-who-is-bigger-than-the-universe, in our own bodies through the gift of silence.

We encounter the Son, Jesus the Christ, the Redeemer, the Word of God who-became-one-of-us, in our own bodies through the very gift of our embodiment.

We encounter the Holy Spirit, the rushing mighty wind who is the Breath of God, who Christ gave to his disciples by breathing upon them (John 20:22), we encounter this Spirit of God in our own bodies through the gift of breath.

Silence is the ikon of the presence of God the Creator. Remember, an ikon is not the same thing as an idol: it’s not a substitute for God, but rather a created object through which we encounter the uncreated God. The silence of creation — including the silence within our own hearts, a silence deeper than all our thoughts and feelings and mental chatter — this silence is a gift from God to us, that brings eternity into our hearts (Ecclesiastes 3:11), that reminds us of the deep silence into which God spoke the first words of creation, the silence that keeps us humble because we can never fully comprehend God or put God into words (or thoughts). The Bible instructs us to keep silence before God (Habakkuk 2:20), so when we keep silence, we place ourselves in the presence of God the Father.

The human body is the ikon of the presence of Christ the Son of God. “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). Christians worship Christ because he is the incarnation — God-made-flesh. So when we seek Christ in our own hearts, it is our very bodies that testify to his presence in our lives. The body is not evil, or an illusion, or something to be ashamed of our gotten rid of — on the contrary, it is a gift from God, to be cherished, cared for, and honored as the grounding of our own “incarnation.” Saint Paul bluntly states “Christ will be exalted in my body” (Philippians 1:20) — so when we embrace our very embodiment, we place ourselves in the presence of God the Son.

Your very breath is the ikon of the presence of the Holy Spirit of God. As I’ve already mentioned, the body is the temple of the Holy Spirit (I Corinthians 3:16, 6:19) — but if the body is the temple of the Spirit, then the breath is the altar on which we sacrifice all to the Spirit who is Love. The very word “Spirit” is related to breath — see the link between inspiration and respiration — and this is true not only in English, but also in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and other languages as well. “Breathe on me, breath of God” goes the old hymn — we know that to breathe is to live (a euphemism for dying is “he breathed his last”), and all life comes from God, so when we embrace our very breath, we place ourselves in the presence of God the Holy Spirit.

Praying the Prayer of Contemplative Awareness

Contemplative prayer, at heart, is simply a prayer-of-awareness. In a nutshell, it is a prayer of “paying attention to God” — at a level deeper than words, than thoughts, than the imagination. Sometimes praying with words, or thoughts, or feelings, or the imagination is important and beautiful. But sometimes we have to lay all those things aside and encounter God directly, in our bodies, in silence, in our breath. We pray to simply place ourselves in God’s presence — and to bask in God’s light and love, no matter what we consciously experience.

Contemplative prayer is the prayer of awareness of silence. Here I commend to you Martin Laird’s wise book Into the Silent Land. We have difficulty simply being silent, and many people actually fear silence or find it makes them deeply uncomfortable. But silence is gentle and serene, so it’s not so much the silence we fear, but our very selves. Learning to place our attention on silence (and not on the ongoing drama in our minds) is the heart of contemplative practice. When we learn to be still and know God (Psalm 46:10), we discover that silence is always in us — and is the doorway through which we encounter God, and God encounters us.

Contemplative prayer is the prayer of awareness of embodiment. Here I commend to you the writings of Anthony de Mello, beginning with his book Sadhana: A Way to God. Perhaps the reason why so many of us find silence fearful and uncomfortable is because we haven’t yet learned how to be present in our own skin. Part of this, frankly, is religion’s own fault: we have for too long endured that tired dualism that says spirit is good, but matter (including the human body) is inferior or even bad. But that is not the gospel! Christ taught us to heal our eyes so that our bodies would be filled with light (Matthew 6:22) — and the healed eye is an eye that sees “singly” which is to say non-dually, i.e. a contemplative eye: in the words of Meister Eckhart, “the eye with which I see God is the eye with which God sees me.” When we honor our body, and learn to rest in simple awareness of our embodiment, that gentle awareness becomes the doorway through which we encounter Christ, and Christ encounters us.

Contemplative prayer is the prayer of awareness of breath. For this dimension of contemplation I commend to you the classic Russian Orthodox text The Way of a Pilgrim. The Orthodox prayer of the heart — Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, Have Mercy on Me — is an invitation to synchronize our prayer with our breath. Another book that looks at breath-as-prayer is David Frenette’s The Path of Centering Prayer — or, for that matter, Martin Laird’s book. Christians often mistakenly assume that breath work is an eastern practice, something associated with Yoga or Zen but not Christianity. Yet we see, especially in the Orthodox churches, a deep recognition that mindful breathing is a way of praying to the Holy Spirit. Breathe in the love of God; breathe out compassion and care for others. Continue indefinitely. When we maintain awareness of our breath, we encounter the Holy Spirit, and the Holy Spirit encounters us.

Contemplating the Trinity

Be silent. Be embodied. Breathe.

Do these three things, and you are contemplating the presence of the Holy Trinity in your life, right here, right now. Without words, without feelings or distractions, without complicated theology or academic abstraction, simply be present, be silent, be embodied, and breathe. And continue.

God is love. God is lover and beloved and the love flowing therein. You are the image and likeness of God. In silence, you are the lover. In your body, you are the beloved. In your breath, you are Love.

Now, my friend: go and set the world on fire.

Want to read more on the Trinity? Check out these resources:

- Anne Hunt, The Trinity: Insights from the Mystics

- Aristotle Papanikolaou, Being With God: Trinity, Apophaticism, and Divine-Human Communion

- Catherine Mowry LaCugna, God For Us: The Trinity and Christian Life

- Cynthia Bourgeault, The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three

- Karl Rahner, The Trinity

- Michael Downey, Altogether Gift: A Trinitarian Spirituality

- Richard Rohr and Mike Morrell, The Divine Dance: The Trinity and Your Transformation

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.