Theosis comes from the Greek θέωσις and literally means “divine state” — Theo (God, divinity) + osis (state or condition). Think of words like theology (God-talk) and kenosis (a state of emptiness) to understand how the word is constructed.

Put simply and succinctly, theosis is the mystical state of being one with God, or embodying union with God. Different theological perspectives will suggest that this is something only available to us at the end of a long process of purification and enlightenment, or that it is something literally knit into our created being, always a part of us if not always recognized and embraced as our divine birthright. Is it a present reality, or a future promise? Or can it paradoxically be both?

Parallel words in the English language include deification and divinization. It is also related to the concept of “union” as in the traditional map of the mystical life: purification (in Greek, katharsis), illumination (theoria) and finally, union (theosis). From this we can see that language of “union with God” or “the unitive life” (as used by Evelyn Underhill) also point to theosis. I think you could also make the case that nonduality as understood in a Christian context is essentially theosis. Christian nonduality, like theosis, is the capacity to see and understand: “God and I are not-two.”

Theosis, like its English equivalents, is a big concept, awe-inspiring in its implications. It can also, depending on your theological backgound, seem unorthodox, if not downright heretical. I remember talking with a friend of mine who was reading Michael Casey’s Fully Human, Fully Divine: An Interactive Christology (a study of the doctrine of divinization in the light of the Gospel of Mark). A lifelong, devout Catholic, she simply couldn’t wrap her head around bold language like “According to the teaching of many Church Fathers, particularly those of the East, Christian life consists not so much in being good as in becoming God.” For my friend, statements like this were complete non-starters. “How can I ‘become God’?” she would scoff. “I’m not capable of creating super-novas!”

Neither is a drop of water capable of creating a tsunami — but just as a drop of water, once immersed in the ocean, becomes one with the ocean, so too the mystics recognize that our destiny as human beings is such utter immersion into the ocean of God’s love that we become — to use language directly from the New Testament — partakers of the divine nature (II Peter 1:4). Probably much of the confusion about theosis stems from this idea that “one with God” means “I run the entire universe.” But that’s not what it means — it simply means “I am one with that creates and sustains all things.”

God became human so that humans might become god. — St. Athanasius

The conservative wing of Christianity has long been uncomfortable with this kind of language, seeing it as at best presumptuous, at worst pantheistic. What greater manifestation of pride, hubris, can there be, than to proclaim oneself as “one with God”? According to this way of thinking, the very idea of deification seems to be sinful, on a par with Lucifer’s refusal to bow down before God.

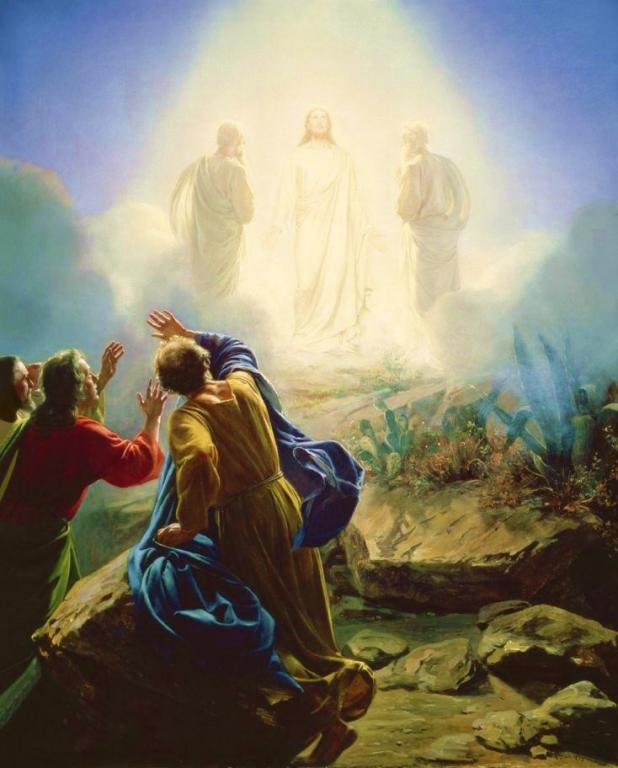

But to reject theosis in this way is to project the worst kind of dualistic thinking on it — a way of seeing the cosmos that overemphasizes humanity’s distance from its own creator. It’s also to ignore the profound Biblical language of union, from the creation myth of Genesis (where God creates humanity in God’s own “image and likeness”) to New Testament language such as Christ’s promise that we can abide in him, as he abides in us (John 15:4) and Paul’s promise that “anyone united with Christ becomes one spirit with him” (I Corinthians 6:17). And if you think “union with Christ” is something different from “union with God,” remember Jesus’s own bold statement of divine union: “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30).

I think for those of us who are not scholars of early Christian history or the Greek language or the writings of the church fathers, perhaps the easiest way to approach the spirituality of theosis is by remembering another important Biblical principle: “God is love.” I like to say “God is Love-with-a-capital-L” — the fountain and source of all love, throughout all time and space. To become partakers of the divine nature sounds less intimidating when we begin by considering that our destiny is to become partakers of divine love. We are created in the image and likeness of love. The spiritual journey: turning away from sin, cultivating virtue, seeking holiness, seeking intimacy with God through prayer and meditation and contemplation — is all one eternal symphony of love responding to Love. Just as in the sacrament of marriage I am made one, through love, with my wife, so too in the mystical life I am given the inestimable gift, entirely by the grace and action of God, of being invited, again through love, to be made one with Love, Love-with-a-capital-L.

So what does all this mean? Again, don’t worry about having to manage supernovas (or, like Jim Carrey’s character in the comic movie Bruce Almighty, having to be responsible for answering the prayers of all beings!). The drop of water is not the ocean, even though it becomes one with the ocean. If you choose to walk the mystical path and to seek nothing less than union with Love, then you are offering yourself to God to become Love-in-human-form. You are still yourself, with all your joys and challenges. But as you “live and move and have your being” in Love, everything does change — because now everything, and every moment, and even every challenge, becomes yet another opportunity to love, to receive and give love, and to be love — with all the promise and possibility that this could entail.

Sounds like an adventure — so what are we waiting for?!?

For Further Exploration

- A.M. Allchin, Participation in God: A Forgotten Strand in Anglican Tradition

- Michael Casey, Fully Human, Fully Divine: An Interactive Christology

- Michael J. Christiansen and Jeffrey Wittung, eds., Partakers of the Divine Nature: The History and Development of Deification in the Christian Traditions

- Stephen Finlan and Vladimir Kharlamov, eds., Theosis: Deification in Christian Theology

- Jules Gross, The Divinization of the Christian According to the Greek Fathers

- Veli-Mati Kärkkäinen, One With God: Salvation as Deification and Justification

- George A. Maloney, S.J., The Undreamed Has Happened: God Lives Within Us

- Georgios I. Mantzaridis, The Deification of Man: St. Gregory Palamas and the Orthodox Tradition

- Panayiotis Nellas, Deification in Christ: The Nature of the Human Person

- Aristotle Papanikolaou, Being With God: Trinity, Apophaticism, and Divine-Human Communion

- Norman Russell, The Doctrine of Deification in the Greek Patristic Tradition

- Archimandrite Christoforos Stavropoulos, Partakers of the Divine Nature

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.