On Friday the Washington Post took a close look at the Mindfulness movement — and how at least in some sectors it has been undermined by good ol’ American narcissism.

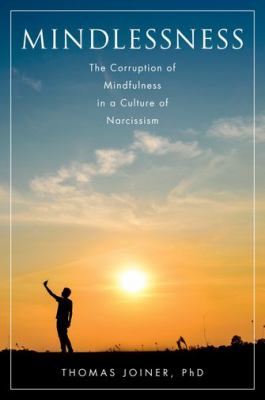

The article is well worth reading: Mindfulness would be good for you. If it weren’t so selfish. It is written by Thomas Joiner, a psychologist who authored a book on this topic, called Mindlessness: The Corruption of Mindfulness in a Culture of Narcissism.

A little over four years ago, I was invited to speak at a small conference on the language of contemplation across religious traditions. About a dozen of us gathered at a Tibetan Buddhist center in California, representing all the world’s great spiritual traditions and sharing ideas with one another about the relationship between meditation, contemplation, language, and culture. The sponsoring organization is involved in translating Tibetan texts into English and other languages, and recognized that there is a perennial tension between trying to capture, in words, a spirituality that is essentially ineffable and indescribable. It was an excellent conference (see below for a video of one of the sessions).

But what I remember, more than anything else, from that conference, was hearing one of the Buddhist speakers talk about his concerns about the mindfulness movement, which he saw as dangerously severing meditation practice from its philosophical and religious matrix. A secularized meditation intended strictly for therapeutic purposes, he warned, will reduce the practice to an ego-centric tool that actually works against the goals of Buddhism — or other faiths.

So when I come across a book like Joiner’s Mindlessness — or, for that matter, Miguel Farias & Catherine Wikholm’s The Buddha Pill, which explores some of these same concerns — it feels like, in Yogi Berra’s famous dictum, “déjà vu all over again.”

I think Joiner does a very good job at acknowledging what is good about mindfulness practice. Even though he suggests that the empirical evidence for mindfulness having therapeutic value is weaker than its boosters would have you believe (another point previous explored by Farias & Wikholm), he writes eloquently about why mindfulness is attractive, and how — at its best — it really does invite the practitioner into a place of deepened awareness and gentle acceptance. He very astutely recognizes that a key to fully entering into mindfulness is humility — I’ll get back to that point.

But he sees problems with how mindfulness is promoted in our society — that the story is all about what mindfulness will do for you. In other words, it reinforces our cultural obsession with the self. In other words, our tendency toward narcissism. And since narcissism and self-obsession are big problems in themselves, mindfulness simply doesn’t help as much as it’s cracked up to, and may actually be unhelpful for those whose root problem is not anxiety or depression but, well, self-obsession.

I agree with Dr. Joiner. But I think this is a problem that our secular culture is not well equipped to address. By stripping meditation of its religious matrix — whether Buddhist or Christian or whatever — we strip it of the very cultural safeguards that are in place to promote simplicity, compassion, service, and self-forgetfulness (humility). In other words, what is needed to make mindfulness a more truly holistic practice — not only psychologically therapeutic but also spiritually healing/liberating — is the very religious content that got discarded when “mindfulness” was first divorced from its historical background in order to be promoted to (and accepted by) the secular medical/scientific community.

It’s a fundamental paradox. Ours is a culture which values self-confidence, assertiveness, peace of mind, extraversion, and other “winner” qualities. Certainly such qualities can contribute to a happy and an effective life, so it is no surprise that our mental healthcare objectives typically involve cultivating these characteristics. Spirituality, on the other hand, invites us into humility, simplicity, receptivity, docility, deep silence/quiet, unknowing, wondering, and even obedience and repentance. Put another way, our secular model of wellness involves the assertion of the self, while the spiritual model of wellness involves dying to the self. Now, please understand — I am not attacking the goals of secular therapy! Many of us have poorly developed egos, and we need therapeutic support to grow a mature and healthy sense of self. We cannot die to ourselves if we have not given birth to a healthy self within us first. But spiritually generally picks up where therapy leaves off.

So the problem with a mindfulness practice divorced from spirituality is that we’ve taken a practice that works best when it is in service to humility — to self-forgetfulness, or dying-t0-self — and we’ve transplanted it into the context of secular therapy, which is all about giving-birth-to-self.

The solution: I think the best bet is to form strategic partnerships between secular mindfulness programs and spiritual centers such as Shambhala Buddhist Centers or Ignatian Retreat Houses. Let’s continue to teach people how to meditate, but let’s make sure they understand that there is a world of spiritual wisdom that must accompany such practice. It’s not optional. But by combining the pure process of mindfulness practice with the self-transcending wisdom of the dharma or Christian contemplation, then what is truly beneficial about mindfulness can more readily make a real difference in peoples’ lives.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.