Have you ever felt desperate for thirst? So hungry for food that you would have done anything to get food into your belly, stat?

Just about a year ago, a friend of mine decided that to celebrate her 50th birthday, she would invite a handful of girlfriends to trek up a really tall mountain with her. Although I would have rather celebrated the occasion with a fruity drink by an ocean in Mexico, I said yes to the adventure of climbing Half Dome in Yosemite.

Lest you believe this a fairytale of the preacher’s imagination, it actually happened. Six of us drove to the national forest on a Thursday afternoon: we would spend the night near the base, then start hiking at five the next morning.

We loaded our backpacks up, mostly with water but also with food we might want to eat along the trail. I refrained from packing a book, for obvious, climbing-straight-up-a-mountain, no-time-to-read purposes, but did bring an extra pair of socks with me.

By the time we started the climb, it was obvious who lived in the mountain goat category and who more so lived in the mountain …platypus category. Although some of the women seemed to scurry upwards without so much as needing to take a breath, I staked claim to the latter category of slow and steady wins the race. Even though I had trained a little bit, I was out of my element – more suited to the waters of Australia than the hills of California.

More than halfway through the day, we finally reached our destination: two of the women, including the birthday girl, officially summitted Half Dome. The rest of us made it to Sub Dome, just below. We were so proud of ourselves. We were so tired and exhausted.

And I was terribly thirsty. Even though I had packed a lot of water, I seemed to need a lot of water, more water than I’d brought in the first place. (I did just liken myself to a semi-aquatic, egg-laying mammal, after all). Before we were even halfway back down the mountain, I knew my supply was dwindling – and even though downhill wasn’t as hard, I knew I wouldn’t make it back to the base without more water.

That’s when one of the mountain goats, if we can call her that, handed me a liter of water. She didn’t need it. She was fine without. She could make do.

She gave me water when I needed it most. She gave me what I most desperately needed at the time.

I tell you this story, because in a way, it’s not all that different from this week’s Gospel reading when Jesus speaks about a desperation of sorts – a kind of eating and drinking we’re invited into, if we’re to live.

In John 6, Jesus shares a simple truth about himself: I am the living bread that came down from heaven, he says to his disciples. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever, and the bread that I give for the life of the world is my flesh.

For those of us who have long called the Church home, who have perhaps even long called ourselves Christians, perhaps it doesn’t strike us as weird that Jesus would refer to himself as a piece of food – or encourage his followers to gobble down the food that he is.

But to the men who had just crossed a lake in search of him, they didn’t know what to think of the declaration. How can this man give us his flesh to eat? Their question is not unwarranted; we too would probably find ourselves asking the same, had we just begun to follow in the way and path of Jesus.

In response, Jesus spells it out a second time: You’ll eat my body. You’ll drink my blood. Because when you do this, you’ll live.

I am, of course, truncating his words, but the sentiment remains the same: When Jesus is our food, he also becomes the life source pulsing through our insides. After all, this is the one who longs to nourish us, the God who longs to sustain us.

This God is The One Who Feeds our spiritual hunger, who quenches our desperate thirst.

“He is our bread, he is our bread, he is our bread,” one writer says. “Our lectionary asks us to linger over this truth for a reason; this teaching is elemental. It is rock bottom. It is the core of who God is, and who we are. May we ever eat, and live.”

What does it then mean to eat of the living God? To eat the flesh and drink the blood and live, truly live, because in gulping down these elements we are leaning into new life, over and over again?

I think sometimes it means recognizing the deep hunger that lives inside each one of us – a deep hunger that only God can satisfy.

This desperation is often quenched when we come to the table and kneel at the altar: The body of Christ, made for you. The blood of Christ, poured out for you. Whenever it happens, however it happens, we are made new, renewed in this act of eating and drinking.

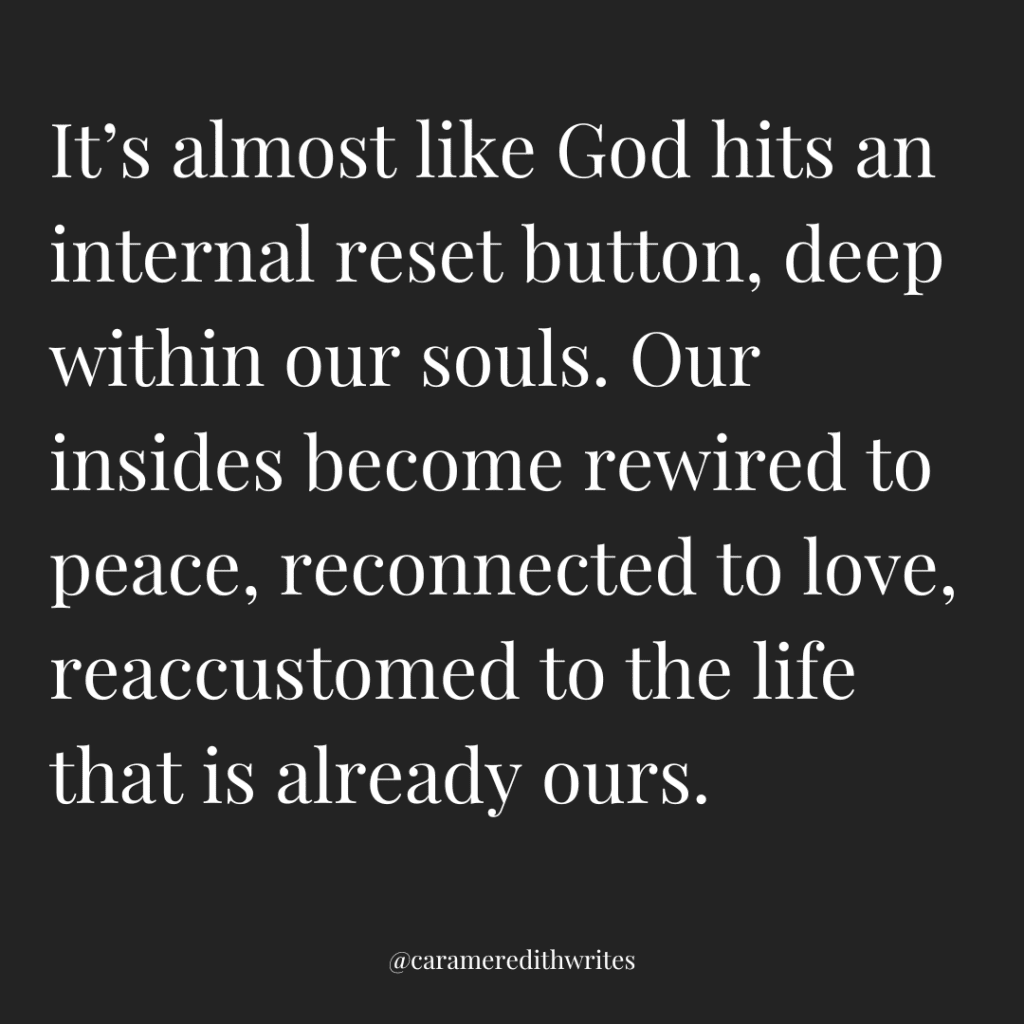

It’s almost like God hits an internal reset button, deep within our souls. Our insides become rewired to peace, reconnected to love, reaccustomed to the life that is already ours.

But I believe something holy also happens in this place, not just at the altar, but also with the people. Because in Protestantism, the church, as in the people of the church, are often, also called the body of Christ.

When we gather together, we are being fleshy, real versions of Christ to one another. We too are quenching one another’s thirsts, feeding each other’s souls.

When my friend Shannon gave me a liter of water on the side of the mountain, she was filling a real, visceral, physical need in me – but she was also being Christ to me.

When we greet one another, when we call one another by name, when we drop off a meal to someone who’s sick, we are being Christ to one another. When we gather afterwards for coffee hour and engage in conversation, when we package up sandwiches, when we mourn together at a funeral of one of our beloveds, here, we are being Christ to one another.

This is not merely the work of the priest, of Christopher and Erin and others who don robes of Holy Orders in the church – but this is the work of the body of Christ, which is to say, to each one of us.

Top-down, and side-to-side, we receive and we give back. Just as our hunger and thirst is quenched, we also work to quench the hunger and thirst of others in the body.

After all, there’s a desperation of eating and drinking we’re invited into, if we’re to live.

And I don’t know about you, but this is a mountain I’m willing to climb …slow as a platypus I may sometimes be, I say yes to this desperation, to and with this God, to and with this body.

Might it be the same for each one of you.

Amen.

—

This is from a sermon given on August 18, 2025 at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in San Rafael, California. If you like this style of writing, you might like this post as well.