In our house, there is typically one rule I try and employ to my nine and eleven-year old children: You will show kindness. You will be kind, in other words. You will be a kind human toward your brother.

Of course, I generally say this when a lack of kindness is evident.

Take a couple days ago, for instance: I’d just picked the boys up from school. It’s mid-afternoon, a time some might say is getting dangerously close to the witching hour, when hunger rises and tiredness abounds and emotions aren’t necessarily one of peace and calm.

When Brother A, we’ll call him, got hot, he placed his feet on top of our car’s air conditioner. This, of course, is something I understand: I too tend to run hot. I don’t want to feel like I’m sweating buckets, like my insides are about to burst out of my skin if I don’t get a little bit of cold air right this moment. But Brother B did not like this scenario, for the air conditioner is one they share. This is also something I also understand: I don’t prefer the smell of stinky feet. No one wants to smell another person’s stinky feet, least of all, your brother’s, which are often the stinkiest of all.

Their not-so-peace-and-calm conversation went something like this:

“Take your feet off the air conditioner!”

“But I’m hot!”

“I don’t care: I don’t want to smell your feet!”

“But I’m hot! Stop telling me what I’m supposed to do!”

On and on it went until I, perhaps also not so kindly, yelled, “BE KIND!” from the front seat, likely followed by “Stop fighting – I’m driving,” or (again) “You will be kind to one another!”

It wasn’t perhaps my best parenting moment, nor was it their best brotherly moment. But when it comes to a singular teaching our family tends to return to, it’s this one.

This week’s lectionary text is not so different when Jesus points to two different passages in the Torah to emphasize the two greatest commandments, the two most important teachings or instructions of all.

In Matthew 22, the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Herodians have been pinging back and forth in an effort to trap Jesus. They want to test him. They want to prove that he is not the one the people should be listening to and learning from, and not the Son of God, as he so claims.

This time, one of the Pharisees, a lawyer, seeks to get him: “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He calls him teacher, knowing he knows the same Jewish scriptures and commands they know. Then, he asks a question that should offer a sure-fire way for those who are against him to victor, once and for all. As one theologian says, if Jesus admits to the first command (to love God), then the Pharisees can claim they’ve been right all along and silence him, due to tradition and purity laws. But if he denies or refuses that command, they can claim sacrilege.

What’s Jesus to do, let alone say, in this moment? Isn’t he caught either way?

Jesus, of course, is not trapped, not when he answers by saying, “’You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”

The passage continues, with Jesus essentially presenting a riddle of messiahship, of his ancestor David, and of one who is called “Lord” – of which he becomes the answer to the riddle and provides a both/and, paradoxical answer. To this, “No one was able to give him answer, nor from that day did anyone dare to ask him any more questions.”

But it’s the vertical-horizonal, loving God and loving other people part of his answer I want to hone in on today.

According to Jesus, this is the most important of all. How then are we to love God and love other people when screaming “BE KIND!” from the front seat doesn’t tend to do the trick? What does it mean to tangibly love our neighbors as ourselves, to love them as we love the one who loved us first?

I think we see an answer to this in Jesus’ words, but also in what’s not said in the text. In this passage, when Jesus is asked a hard question, he extends the conversation. He points back to his – and theirs – Jewish identity. And he answers others well.

He knows the lawyer who asked him this question asked so he could fall and be proved wrong. But when Jesus responds, he responds with dignity. He offers the man the benefit of the doubt; he continues to engage him in conversation, not to prove that he is right but to honor his personhood and fulfill his mission of human dignity.

I see you …and I honor you.

I see you …and I honor the human you are, for the human in me honors the human in you.

I write the following in my first book:

For we humans are knit by our humanity, by the imago Dei present in every single one of us. We are bound by a law of mutuality that connects us, by “the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity” called ubuntu. Although the word originates from the Nguni Bantu people, Desmond Tutu made the phrase universal. For here, a person is a person through other people. Here, I am because you are. Here, a human-to-human kind of honoring happens only because of the humanity that binds us together, and here, we belong, one to the other.

When it comes to loving God and loving other people, if we look at Jesus’s response to the lawyer, we are reminded that making the two greatest commandments our most important thing happens when we respond to one another with dignity.

When we pass the peace to one another? Dignity. When we’re walking the dog and still say hello to the neighbor who won’t say hello to us, when we’re making Costco runs and let crazy cart drivers go first in the peanut butter aisle? Dignity.

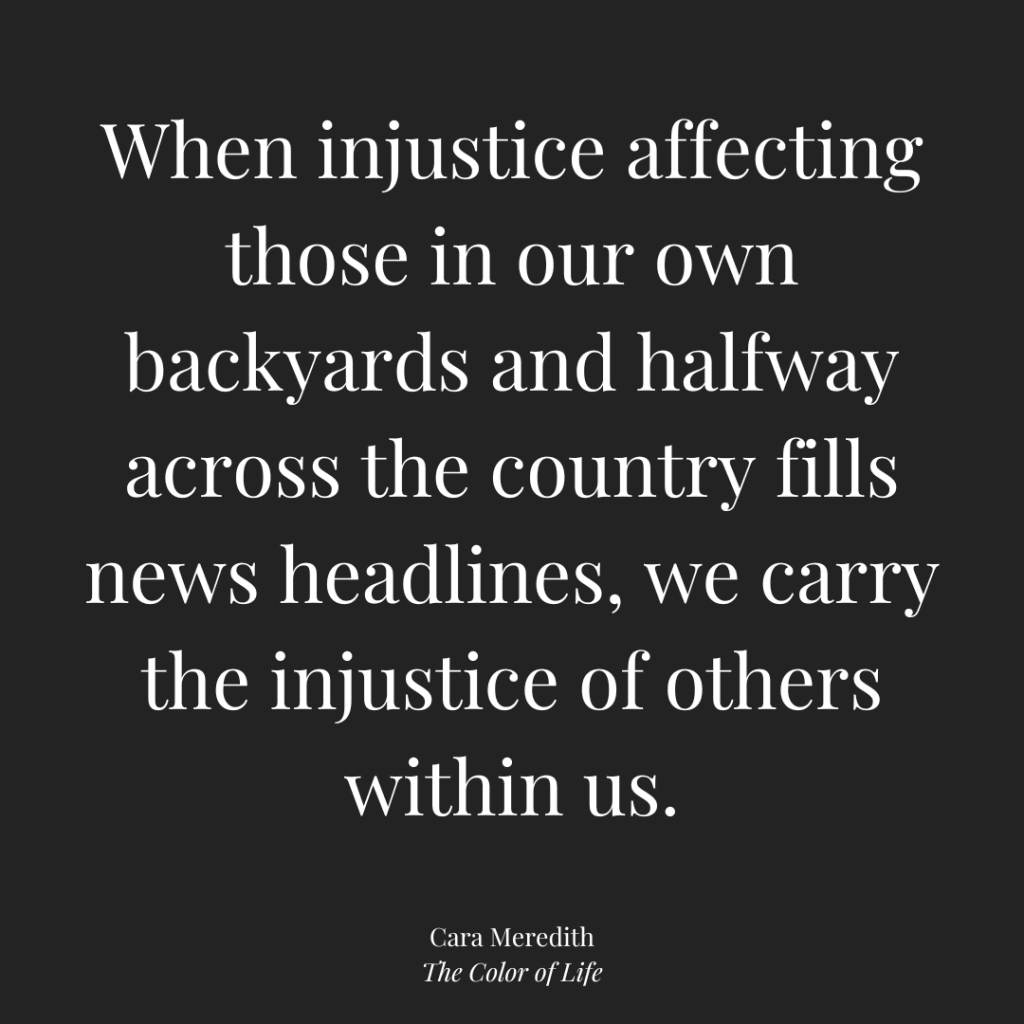

But also, “When injustice affecting those in our own backyards and halfway across the country fills news headlines, we carry the injustice of others within us” (here).

We carry this injustice within us when mass shootings that should have never happened in the first place, happen to our neighbors in Maine. We carry this injustice within us when racial hate continues to happen to our Black and brown family, and especially within the Bay Area, to our Asian family as well.

And we carry this injustice when war breaks out between Israel and Palestine, and others beg us also pick a side and choose between the two countries – to this, perhaps, we can only lean into author and activist Shane Claiborne’s reminder that “Every single Palestinian is made in the image of God. Every single one. Every single Israeli is made in the image of God. Every single one.” We grieve every life lost, as we think on the one who taught us to respond with dignity.

Lord, have mercy, we cry out.

Christ have mercy, we say.

Because sometimes, that is the only thing we can say.

As we leave these doors today, might each one of us be reminded of the up-down, left-right and back again teaching to love God and love others well, showering dignity on the fleshy, messy, beautiful human beings in our midst – and might we, in turn, receive this love given us.

Amen.

—

This sermon was preached on October 29, 2023 at Grace Episcopal Church in Martinez, California. Much has changed, particularly around the Israel-Hamas War, and I now call for an immediate cease fire to this unnecessary destruction. That being said, if you resonated with these words, you also might like this sermon excerpt on the same chapter.