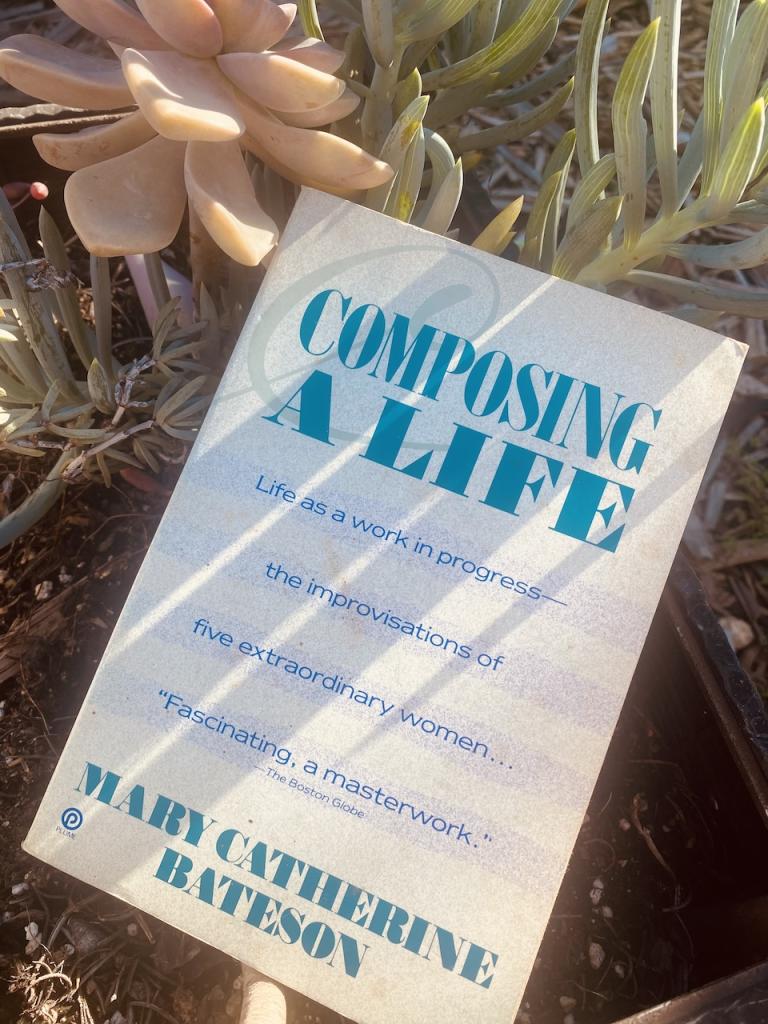

A friend recently passed along the following book:

I think you’ll like it, she said, and mostly, I did.

Composing a Life tells the stories of five different women, but even more, it tells a story of life and of how all the different facets of who we are often act a work in progress. As the back cover reads, the author’s “life-affirming conclusion is that life is an improvisational art form, and that the interruptions, conflicted priorities, and exigencies that are a part of all of our lives can, and should, be seen as a source of wisdom.”

Thread by thread, we are each composing a life, even if we don’t often realize it in the moment.

As I read the book, I thought all the jobs I’ve held since I first started paying taxes a long, long time ago:

- server

- lifeguard

- security guard

- phone solicitor

- tree counter

- front desk worker

- resident advisor

- barista

- ropes course guide

- program director

- teacher

- speaker

- middle school director

- area director

- writer

- youth pastor

- professor

- editor

- communications strategist

- minister

- director of development

I’m sure there are several jobs I’m actually forgetting in the big scheme of things (although whether I’ve blocked them from memory is another question altogether).

However, even a brief survey of the aforementioned jobs shows me a through line with threads of working on the frontlines with people, doing a whole lot with words, and eventually, engaging in roles that involve a fair amount of thinking and strategy.

Like Mary Catherine Bateson, the author, “the identity of writer remains truest to my sense of self” (223). She goes on to say the following:

Writing is the most portable form of creativity, sometimes a vocation and sometimes an avocation. Each time some other engagement has been interrupted, I have gone back to clean paper. Otherwise I would probably be trapped today in narrow expertise, working in some prestigious and arid university department. Writing has been the constancy through which I have reinvented myself after every uprooting (223).

Because here’s the thing: a fair amount of uprooting exists that you can’t necessarily see on the paper. There’s always something hidden between the lines.

I think again of my list: what’s not said in-between the bullet points of “area director” and “writer” is the complete uprooting of my faith after I left full-time ministry.

The following scene plays out in my next book, Church Camp. When I was asked to speak at camp again, I didn’t realize how much upheaval had happened until I stood on stage:

When June rolled around, I stood on stage, belly sticking out nearly a foot from my midsection. I tried to tell all the old stories, the ones that found me bouncing and jumping across the creaky wooden stage, enraptured laughter the only response from the other side. But I was out of breath, my sentence short — staccato notes stuck into the middle of a rolling concerto. I waddled from one side of the platform to the other, unable to tell the stories like I wanted to tell them, unable to herald the God I was being paid to proclaim.

Maybe the most fraudulent piece of all was that I could barely said the word God, at least not that week. I could say Jesus, if I was reading a text, but in the aftermath of explanations and stories and invitations, my mouth could not regurgitate anything else. Lord was out of the question, Father not even comprehensible. I couldn’t say those names because I didn’t know what I believed anymore (xiv).

I had to figure out how to return to center after this particular instance of uprooting, an uprooting that felt particularly vulnerable given the very public “Professional Christian” role I’d played for much of my life.

But as Bateson reminds in her book, this too is normal, if not expected in the story of one’s life.

Uprooting happens. Interruptions are just part of the deal. Conflicted priorities, sometimes, especially for women when it comes to their roles as caregivers, spring up at the most unexpected times. And urgent needs or demands that weren’t on the docket a day, a month, a year before, suddenly take up more space and time and energy than we ever could have anticipated.

Because all of this is simply a part of composing a life, thread by thread by spindly little thread.

And sometimes, simply having it named, is exactly what we need to hear.

—

Here’s an idea: Grab a piece of paper and write down every job you’ve ever had that you can remember in the moment. Then, start to look for the through lines, the threads that weave one particular role to another, that tell a story of the composition of your life.