I recently won the following book from Englewood Review of Books:

Englewood, if you don’t know, is one of my favorite places to go for book reviews. (It’s also a place I regularly write for, such as this early fall review for Sarah McCammon’s The Exvangelicals).

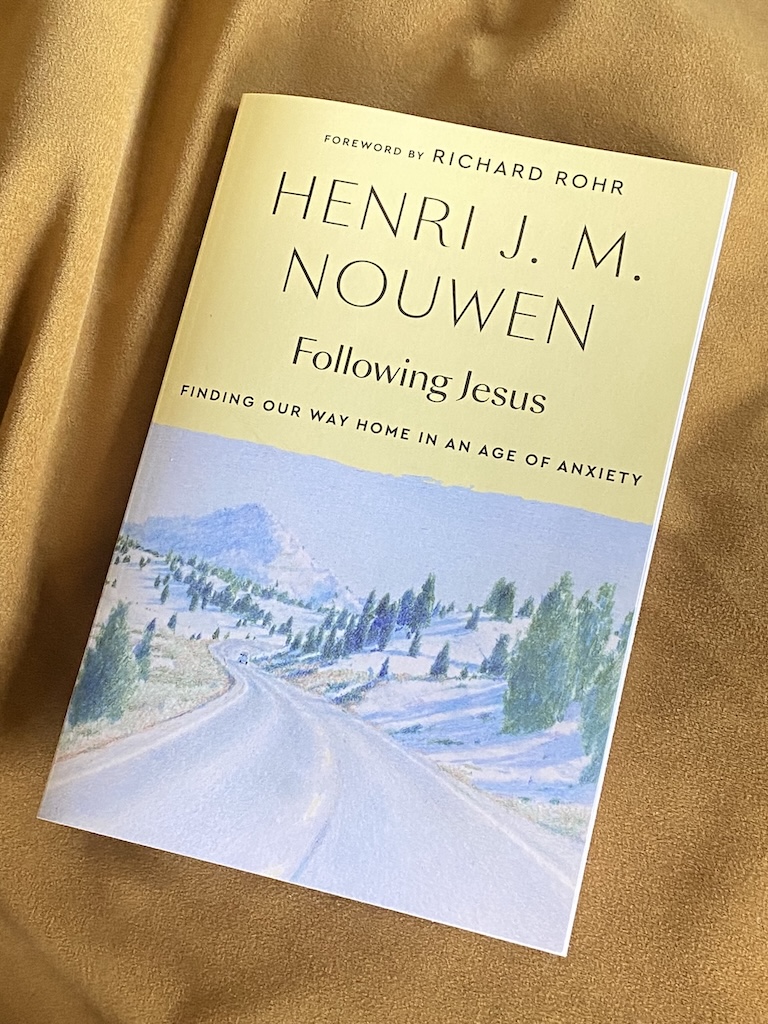

Nouwen’s book, Following Jesus, is short, and as per his usual, a gift. Although I’d not read any of his writings in years, returning to his thoughts felt like sitting down to coffee with an old friend once again.

I wondered how I’d feel about the book, given that when I was very, very into Nouwen, I was also very, very evangelical (and now I am very, very not, or so I’d like to think). Just as we humans too often create God, and dare I say one another, in our own image, I think I’d also created Nouwen in my own image: As someone who believed in the very same version of God and Christianity that I believed in as well.

Now, I see Nouwen through a different lens, a lens I imagine might be a little more realistic and authentic to who he really was instead of who I’d assumed him to be.

This particular collection of essays falls under the subtitle, “Finding Our Way Home in an Age of Anxiety,” and wouldn’t you say it’s rather appropriate to the world we find ourselves living in today?

Every day, we way up to a barrage of information—of the rising price of eggs, the confirmation of completely unqualified individuals into various positions of leadership in Washington, and the devastation of a 90-day freeze on USAID moneys (and subsequent) programs around the world. Our country is on a path toward American authoritarianism and many of us feel like there’s not anything we can do about the inevitable destruction that lies ahead.

What does it mean to find our way home in an age of anxiety?

Nouwen gives the following thoughts on hoarding, which feels particularly relevant given many of the greedy instructives happening at the hands of the current administration:

When we are concerned that there isn’t enough, our first response is to start hoarding. We start hoarding the bread, the fish. Hoarding honor. Hoarding affection, hoarding knowledge. Hoarding ideas.

If we start hoarding we find ourselves with enemies.

There are always people who will say, “You have much more than me.” You might say, “I know, but I need it for emergency situations.” They respond, “But I need it now. I am hungry now.” “I want to know this now.” “I want to build this now.”

If we think with a scarcity mentality we find ourselves with enemies who want to take some of what we have hoarded. We are more and more afraid, because the more we have, the more people want our surplus. The more surplus we have, the more we are going to build walls around what we have hoarded.

The higher the walls get, the more fear we have of the enemies we imagine outside the walls. We start building bombs to protect us from our imagined enemies, and then we get scared of the bombs that our enemies might build in retaliation. We find ourselves in a prison that we build ourselves because of a fear that comes out of a mentality of scarcity. Of not having enough.

Think about it. How do you hold on to things?

The U.S. government, in an effort to make things more efficient (but also, again, in an effort to employ authoritarianism into every nook and cranny of life), has made hoarding a regular, acceptable practice.

I think specifically of the destruction, and ultimately, the death, that comes with ending USAID programs around the world.

In an article I recently penned for The Living Church (which hasn’t yet been published), I wrote about the devastation of the USAID freeze, particularly on the war-torn country of Sudan.

In Sudan and around the world, food sits in ports and at check points, waiting for distribution. But because of the freeze, humanitarian organizations and third-party contractors are unable to distribute the food to those who need it most.

People are literally dying (or as one report estimates, expected to die of starvation within 10 to 20 days) while a surplus of food sits there, rotting and going bad.

The desire to hoard our resources has resulted in a hoarding (and subsequent expulsion) that literally could be keeping people alive but is instead causing death.

My God.

What does it then mean to rid ourselves of a scarcity mentality? If Nouwen posits that we are all, indeed, hoarding in one way, shape, or form, how are you holding onto things?

I don’t necessarily have any answers, but I do know that there’s another, better way I want to live.

As I write this post, I sit under a pile of blankets on the marigold couch in the living room. To my left is a windowsill full of plant cuttings and seedlings: passionfruit, lettuce, and mint, to name a few. Beyond that, a table of tomato and cucumber and zucchini seedlings, waiting for transplant to bigger containers, and someday, to the backyard garden.

If we’re lucky, the green that dots the corner of my living room will feed us abundantly during the late spring and summer months, and then, after canning and freezing, on into fall and winter too.

But these the plantings are not just for me.

As any gardener knows, when you sow from seed, it’s natural (and smart) to plant two or three seeds for every one plant. Seeds go bad. They die. They don’t sprout. But also, sometimes, they thrive, all taking root and finding a home in the dirt.

When that happens, I see no need for four zucchini plants when Lord knows two are enough to feed a small nation. As it goes, I’ll plant two but then I’ll give two away to my neighbors. I’ll put trays of seedlings out on the front porch, because why live with scarcity when we can be marked by generosity?

Why throw them into the compost pile when we can instead feed our neighbors?

It’s a thought.