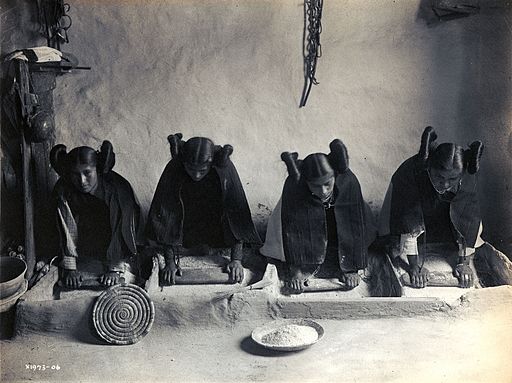

The Hopi word for “women” is “momoyam.” Bees.

And the reason is never more apparent than at weddings, funerals and religious ceremonies. For those events, swarms of female relations and in laws fill village kitchens to cook for the hordes of visitors who will feast at their tables sometimes for several days.

They truly are like worker bees, born programmed to handle the needed tasks. It’s uncanny how almost all the women prepare traditional dishes and perform ceremonial duties the same way.

They fall into a natural rhythm, everyone doing her part perfectly. Kitchen tables turn into big assembly lines creating mountains of delectables and other ceremonial necessities with equal ease.

As a non-Native in law, I was not born to go with that flow. But when I finally went wading in, loving hands reached out to guide me through.

And this week, when I was back home on Hopi for the burial of our beloved “So’o” (Grandmother) Delores, who had so graciously welcomed me into her world back when I first arrived on the rez, I was reminded what it was like to live in a world where women rule.

You see, traditionally, on Hopi, all property is still, in most cases, owned by and passed down through the women of the family. Children, at one time, received their mother’s last name. And many new wives still hope for a girl first, to hand things down to.

Take that, James Brown.

Men work for the women, happily and gratefully. They are amply rewarded, of course. For assisting with the traditional funeral ceremonies and burial this week, they hauled home huge laundry baskets full of gifts and food after being fed like kings when their work was done.

At those feasts, the women flit from table to table with huge bowls and platters, refilling, restocking with that same amazing efficiency. They will only sit down to eat after all the men and guests have finished. That, too, is tradition.

New wives and young “trainees” who sit down on the job are teased back into action. The Hopi way is to “joke” about these things, until the subject of those jokes gets the idea.

It doesn’t take long. Trust me.

When I first arrived on Hopi almost two decades ago, a brash young city girl fresh from the features department of the Chicago Sun Times, I didn’t see this as “woman power” at first. I was impressed by their skills, but a bit perturbed, like many outsiders, as I watched those “subservient” swarms.

I didn’t know Hopi history or culture well enough yet. But once swept into those swarms often enough I understood and felt the power that rules their world. Hopi women, to this day, have an innate sense of purpose and self-worth I feel nowhere else in the world. And I’ve met some powerful women in my time.

Their equally awe-inspiring serenity is fed by that. They are the queens of all they survey, literally. So when they “swarm” it’s with authority. Nothing happens “out home” without women. In some cases, ceremonies cannot begin until a woman says so or is present.

In fact, those swarms are ceremonies. Prayer offerings. Their entire lives are prayer. The way they do things, say things, it’s all about their ancient beliefs and life ways. So what you’re watching, whatever you’re watching on Hopi, is how to combine the sacred and secular, seamlessly.

I am always stunned and delighted to watch them move back and forth from the dominant culture to their own ancient one. I’ve never forgotten the sight of a toddler watching cartoons on TV while stomping and rattling and singing an old katsina song at the same time.

Oh, here’s another one—can’t forget this.

After the last batch of somiviki—a type of sweet blue corn tamale—had been made, Delores’ sister stopped to watch a little TV. And she pointed a crooked, wrinkly finger at the dude in the horned Viking hat on the screen and said, “He’s horny, huh?” And gave me that little “tsk” thing you hear at the end of many a Native American quip.

And then she toddled back to the kitchen to direct clean-up traffic masterfully in Hopi.

They are always Hopi, looking out, bemused, at the other worlds they’re forced to deal with. Their traditions tell them how to deal with them. And give them the strength to deal with them gracefully.

Perhaps that’s also why the buzzing in those swarms is almost always laughter. Often about the men they’ll be feeding over the next few days. In fact, if what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, what happens on Hopi gets laughed about on those “assembly lines.” It’s hard to keep a secret from the swarms.

This visit, I found out that a lot of what’s laughed about in those swarms now also ends up on Facebook. During a rare pause, I looked over to see all the ladies at the table busy swiping and tapping IPhone screens to catch up on or contribute to their timelines.

Yes, technology has come to Hopi, too. My Hopi sister Darlene’s huge, comfy house has Direct TV, the Internet and all the familiar comforts of an American home, though it’s far more expensive and sometimes complicated to keep it that way.

But she is still very Hopi. So the morning after we sent So’o “home,” she rose at dawn to offer up prayers as always. There she was, a tiny silhouette against the vast, fiery sky, giving thanks in the profound silence of a Hopi morning. And no doubt trying to adjust to not having So’o come down the hill for breakfast anymore.

I slipped out to take a picture of the sunrise. And to give thanks, too, for having her and all those wonderful women to come “home” to.

The “buzz” in my head will fade away in a few days. The love, never.

Photo credit: Edward S. Curtis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons