I find it laughable that people package Catholic sexual mores into the same box as the repressed, bourgeois, puritanical vision of sex that the Sexual Revolutionaries rebelled against not too long ago. The Catholic vision of sex violently rips off the pretty satin bow of “normalcy” that rests uncomfortably on top of that oh-so-confining box, almost like the tightly buttoned clothing of your oh-so-repressed grandma (modest is hottest!). But as Chris West will explain (theatrically so) to you, Catholic sexual morality transcends the confining norms of both your puritanical grandma and your sexually liberated aunt (who can’t seem to stop reminiscing about the “good old day” at Woodstock).

Catholic morality surely does not take its cues from the modern idea that happiness comes from releasing our primal, animalistic instincts. Nor does it preach that the body and sexual desire are demonic manifestations that are obstacles to spiritual growth, as some heretical and pre-Christian thinkers might have it. The Church’s moral teachings grow organically out of an anthropology that affirms that in each human heart exists an infinite longing for love and happiness. In its purest expression, sexuality is a springboard that launches us into communion with the infinite Mystery Himself.

The Catholic sexual imagination is anything but normal and boring-it’s weird, crazy, and at times, mysterious. And yet so many young Catholics are oblivious to the uniqueness of what the Church offers them. If only they knew what they were missing out on! It might help to start by introducing them to some of the weird ways that the saints lived out their sexuality.

Let’s go all the way back in time to St. Mary Magdalene, the “town whore,” who developed quite a reputation for herself without the help of an Instagram or Snapchat account (…and that’s really saying something). After meeting Christ, her “thirst” for love from other men reached a true climax-never had she met a man that could love her as he did. What’s interesting is that the image of the Magdalene has been played with throughout history, oftentimes trying to fit her into one of the boxes of the release/repress paradigm. Either she’s been “born again,” leaving behind her sloppy past and forgetting the thirst that won her her reputation, or she’s actually Jesus’ secret sexual lover…an obvious fact which (according to Dan Brown) the repressive Catholic Church doesn’t want you to know about. It seems like people on both ends of the paradigm are afraid of someone retaining their thirst, their feelings and longings, while at the same time channeling them towards a greater love that couldn’t be fully expressed in conjugal relations.

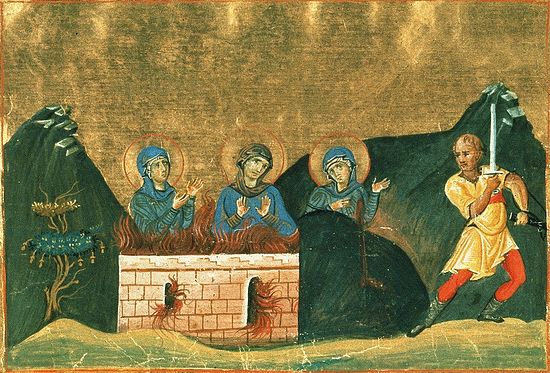

Not too long after the death and resurrection of the Savior-whose body was simultaneously celibate and the physical manifestation of infinite love and desire-we find a long line of women who were so madly in love with this man that they were willing to not only deny the sexual invitations of other men, but were willing to deny their own lives. The virgin martyrs of the late Roman Empire all follow a similar narrative of being set up with a high-ranking suitor, refusing to marry out of their devotion to Christ, and being killed for their audacity to transgress the political, moral, and sexual norms of the times. Agnes, Lucy, Philomena, Cecilia, Anastasia, Bibiana….the list goes on and on.

The strangest of the virgin martyrs is probably Agatha, who was martyred in Catania, Sicily in 251 under Decius. Yet another one of those rogue Christian girls who refused to marry a noble, she was jailed and endured a series of tortures before being killed, one of which involved her breast being chopped off. Agatha is often depicted in paintings and statues holding a tray serving two severed breasts, much to the confusion of many a Catholic youth who was dragged out of bed to go to Mass on Sunday morning.

But wait, it gets even weirder. In her hometown of Catania, the tradition of baking minni di virgini (breasts of the virgins) began as a way to commemorate the town’s patroness on her feast day. These scrumptious little treats are shaped like breasts, with red cherries on top. So much for Catholic tradition making us feel ashamed of our bodies.

The visibility of “private parts” in Catholic art bear witness to the divine Mystery in whose image we are made. The body is neither something to be ashamed of nor an object to be used for pleasure. Rather, the body holds the mark of its Creator, who invites us to use our bodies to participate in the divine work of sustaining this world and preparing us for the world beyond. Take the numerous examples of the exposure of the Virgin Mary’s breasts in several well-known paintings. One of the most curious is the 1650 Miraculous Lactation of St. Bernard, in which St. Bernard of Clairvaux is seen kneeling in front of the Virgin Mary, whose breast is squirting milk through the air and into his mouth. Most images we find today of females with exposed body parts emphasize the usefulness of the woman’s body in pleasing men (and women) in sexual ways. Juxtapose that against this image, who portrays the woman’s exposed body as a means to emphasize the “feminine genius,” the woman’s unique power to carry, nourish, and foster the growth of humanity, both on a bodily and spiritual level.

Aside from the accusations that the Church encourages us to feel ashamed of the body, Catholicism is said to enshrine culturally constructed gender norms. But once again, the witness of several Catholic saints would beg to differ. Take the Roman soldier martyr, Sebastian, who in 287 was martyred under Diocletian. Sebastian is a favorite among artists, having been painted by many through the centuries. An elusive figure, Sebastian’s tale is reinterpreted in art, placing a variety of emphases on the scene of his martyrdom, some of which are imagined, others finding their roots in pre-Christian themes.

Camille Paglia recognizes in Sebastian the Greek ideal of youthful male aesthetic beauty, embodied by the god Adonis, and celebrated in the military and schools of philosophy of Ancient Greece through the pederastic sodomization of “beautiful boys” by their mentors.

Sebastian, the Christianized Adonis, carries the ideals of youthful, aesthetic, and seemingly feminized, male beauty, the arrows penetrating his nearly nude body juxtaposing tones of the sacred and profane. Do these arrows represent the sanctification of aestheticism, his beautiful flesh now destroyed, scourged, “crucified,” in the name of his love for Christ? Or do they secretly hint at the homoerotic undertones of his pagan ancestor, commemorating the tradition of pederasty in classical Greek society?

We also find the lines of gender and sexuality blurred in the mystical poetry of several male religious. Their love for the God-man takes on an almost erotic passion, and identifytheir poetic “I” with the feminine image of Christ’s bride. Perhaps the most noteworthy of these mystics would be the 16th century Carmelite friar, John of the Cross. His Dark Night of the Soul portrays a lover who sets out in the darkness and secrecy of the night to find her beloved. At the end of the poem, we find the two lovers in utter tranquility, passionately caressing each other’s bodies:

And on my flowering breast/Which I had kept for him and him alone/He slept as I caressed/And loved him for my own…

And from the castle wall/The wind came down to winnow through his hair/Bidding his fingers fall,/Searing my throat with air/And all my senses were suspended there.

I stayed there to forget./There on my lover, face to face, I lay…

While John is hardly espousing a form of proto-gender theory that would call into question the givenness of sexual differentiation, he does perhaps open up a space which transgresses culturally constructed norms of masculinity and femininity. The ambiguous identity of his poetic “I” affirms the inherent sense of mystery which is laden within our experience of gender. Art also testifies to the latent sexual ambiguity that flows through the history of medieval monasticism. Take Francisco Ribalta’s 1626 painting Christ Embracing St. Bernard, which depicts the tender, bodily embrace between Lover and beloved, Bridegroom and bride.

(Also check out Max Lindenman’s awesome reflection on the homoerotic imagery of Christocentric piety.)

My favorite of all the weird stuff within the Catholic sexual imagination is Bernini’s infamous masterpiece The Ecstasy of St. Teresa. A fellow Carmelite and “Clare” to John’s “Francis,” Teresa also employed erotic imagery throughout her writings. I once showed one of my classes an image of the statue, asking them to describe Teresa’s facial expression.

“It looks like she’s dying…either that, or she’s feeling extreme pleasure, almost like an orgasm.”

“No, stupid,” exclaimed another student. “There an angel next to her, obviously it’s something spiritual.”

“Could it be possible for her to be going through an experience of pleasure, death, and God all at the same time?” I asked them.

Teresa’s own account of her ecstasy says it all:

I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the iron’s point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God. The pain is not bodily, but spiritual; though the body has its share in it. It is a caressing of love so sweet which now takes place between the soul and God, that I pray God of His goodness to make him experience it who may think that I am lying.

Death, Eros, and the Divine. All wrapped up together and exploding in this experience of ecstatic union between herself and Christ.

This is perhaps why the French call an orgasm la petite mort, the small death. In a sense, we die to ourselves when we engaged in sexual intercourse, opening up space for the “other” to enter into our own sphere of existence. Through this death is born union, and quite possibly, new life. Yet even the experience of marital union and bringing new life into this world do not fully quench the infinite yearning for love that remains in our hearts. Through the renunciation of sex and dying to their own will, celibates open themselves up to a deeper union which recalls us all to the true orientation and purpose of our sexuality: the love of God himself. Perhaps this is part of the reason for the Church’s “weird” teaching about artificial contraception. The openness to procreation is what affirms the link between our sexuality and the yearning for our divine Creator.

Parents and educators are competing with a culture that not only proposes a different vision of sex to our youth, but shoves it down their throats and makes it nearly impossible (and at times, illegal) to escape. So don’t let your soul be downcast when your students or kids dismiss the profundity of these witnesses to the Catholic sexual imagination. It takes time for the seeds of the truth to grow in all of our souls. In addition to exposing them to the stories and art of these Christians, it is also worthwhile to make sure young people spend time with those who live out their sexuality in ways that transgress the norms of both contemporary “revolutionary” culture and the puritanical ideal of “normalcy.”

Enroll them in a school run by a religious order, or have them work at a soup kitchen run by nuns or friars. It’s important for them to see that our bodies and our thirst for communion does not have to be repressed and ignored, nor does it have to be released through a libertine lifestyle that masquerades as “real love” and freedom.

Take Lord Sebastian Flyte of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, who teeters between the repressive expectations of his mother and a reckless lifestyle of alcoholism, homosexuality, and debauchery. This schizophrenic back and forth eventually ends him up in a Tunisian monastery-hospital. The monks’ charitable witness to the tender embrace of Christ’s selfless AND bodily love during Sebastian’s time of need allows him to die a peaceful and Christian death.

Our bodies are gifts, and are fully liberated when they seek to give to others rather than to use them for pleasure. Young people should be encouraged to find joy in channeling their bodily energies toward the service of those who are in need, and seeking a Beauty whose flame lasts longer than the scintillating but temporary sparks of eros.