This is the second article in a series entitled “My Mediterranean Adventures”

I approached my third trip up to the Acropolis with a cynical boredom. As much as I appreciate “cultural visits” to artistic and architectural establishments, the ruins of Classical Greece and Rome never really did anything for me.

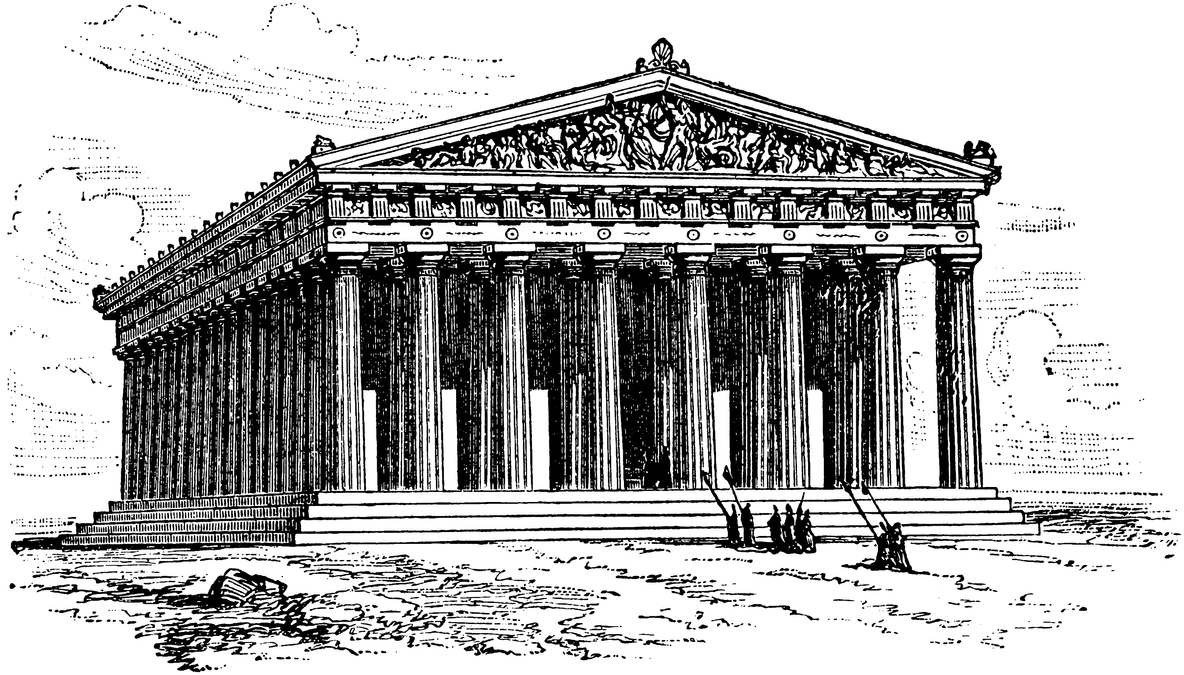

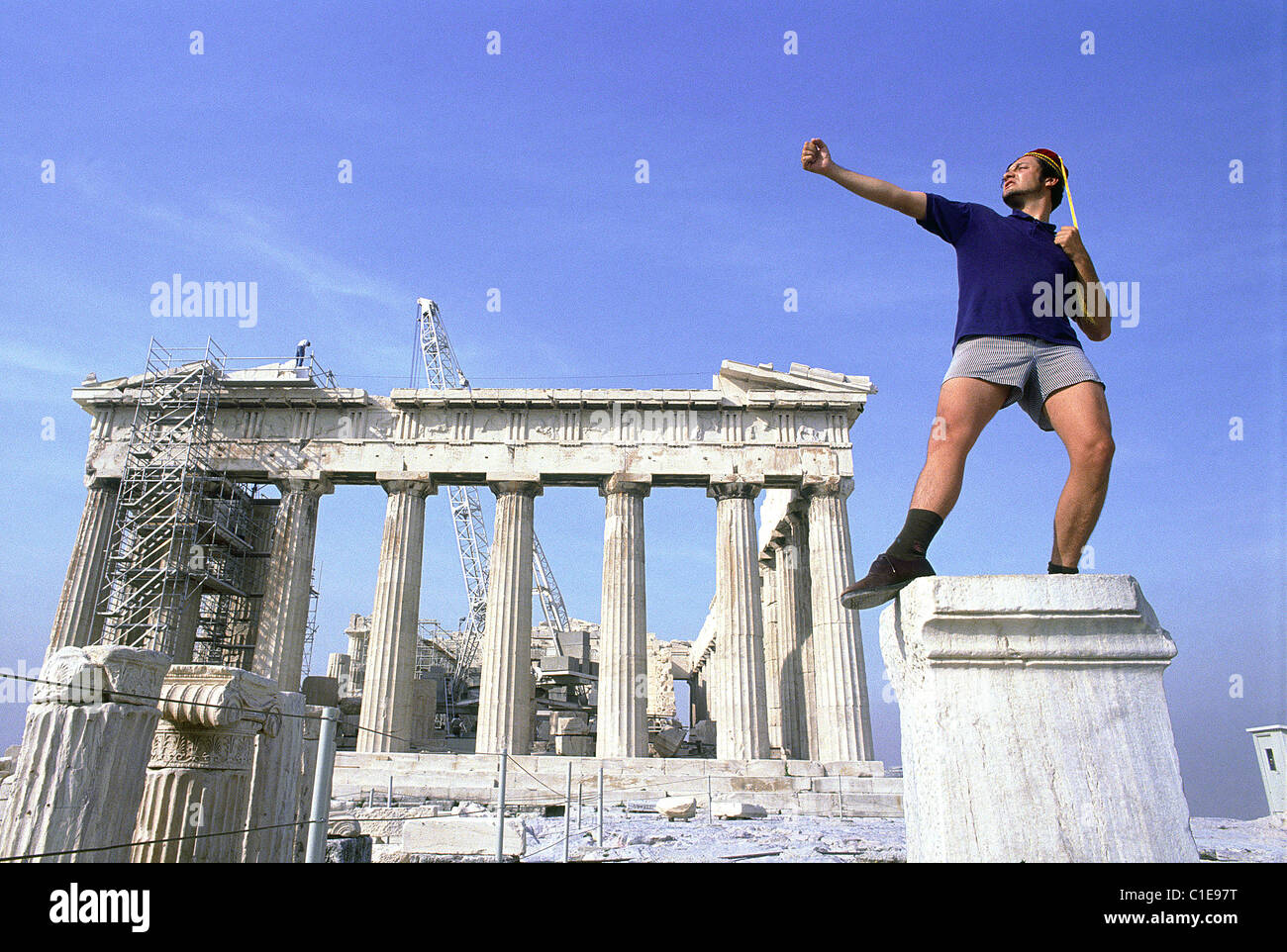

My first trip there fourteen years ago was filled with a naive, instinctual excitement…I posed in front of the Parthenon emulating some generic ancient athlete, enthusiastically showing my friends the photos upon my return. During the second trip I was just apathetic—my “been there, done that” attitude drowning out the puerile excitement I once experienced.

This past trip, I took pleasure in mocking the plebeian tourists as they took their instagram-ready photos. If only they realized how foolish they looked…and how little the people scrolling upon it in their news feeds will actually care about it.

But as I gazed upon the crumbling marble structures this third time, I couldn’t help but recognize a certain grandeur and beauty—in the Parthenon particularly. Under the brilliance of the noonday Greek sun, its immensity and high reaching columns made me ask: what could be the motivation for erecting such a structure?

Ancient Greek religion and philosophy equated aesthetic beauty and strength with divinity. The size, white color, and proportionate ornamentation of edifices like the Parthenon exemplify the Greek notion of the Supreme Being. Humans not only ought not only worship the greatness of this Being—it is an ideal to be emulated as closely as possible. It follows that many of the citizens that ancient Greeks commemorated were known for their physical beauty, military or athletic strength, or intelligence.

For a Christian visitor, the religious awareness encapsulated in buildings like the Parthenon can’t help but provoke a sense of respect and awe: how did these gentiles before the time of Christ intuit all this? The nearby site of the Areopagus stands as a 2000 year old reminder of just how much the pagan religiosity and philosophical thought of the Greeks predisposed them to faith in Christ. Their altar to the unknown god may as well have been waiting for a cross to be placed at its center.

Even so, the paradoxical Christian claim that the Infinite God inhabited the finite world was at best laughably ridiculous to a pagan Greek, and at worst, blasphemous. How could God, in his perfect beauty, strength and intelligence, descend into the earthly, imperfect, mundane world?

German philosopher Max Scheler points out the the Christian notion of perfection transcends the more worldly version of the pagans. God is not a static, faceless entity, an ideal form in another realm. Rather, the Christian God moves; He is the generator and sustainer of all reality. He demonstrates his perfection less through feats of strength and might, but rather through charity, desiring to give life to the weak, to the point of being willing to become weak himself.

Accordingly, the figures commemorated in Christian churches are exalted not for their aesthetic beauty or military prowess, but for their childlike humility and desire. Now, it’s the ugly, the weak, and the fool who are deemed to be the exemplars of true beauty, strength, and intelligence.

The architecture of the churches I visited reflected this different view of beauty and perfection. The seventeenth century Spanish baroque churches of Andalucia are marked by their overly embellished details, with altar pieces that soared toward the ceilings, glittered with gold leaf and dramatically carved statues of saints decorating the alcoves.

This style emphatically juxtaposes grandiosity and suffering, the relationship between them emanating from the drama of the Christian deity whose love was so strong that He embraced the worst of human sufferings and, through this embrace it, defeated it.

I was enamored by the verging on decadent gilded altar pieces and the bloody, agonized statues of Christ and his sorrow-stricken mother—the seven sword impaling her heart, as tears dripped down her face into her human hair and eventually into her multilayered dress-the latter two being a testament to the devotion of her devotees. Bawdy and excessive as this style may be, I couldn’t help but feel at home. I, a weak and often miserable human being, whose tragically limited nature impedes his capacity to attain the perfection and greatness he longs for, am accounted for here. My sorrows are heard, as well my desire for the Ultimate. I can exist in my totality, contradictions and all, in this space, without having to censor any part of my being, for an answer to my unceasing need for beauty, truth, goodness, and mercy is made tangible here.

It’s precisely my unceasing neediness that draw me into unity with the others who enter this space, opening the door to a true sense of community. While I may never have met the elderly people I attended week day mass with, and probably never will see them again, I felt united to their hearts. Not in a sentimental way, but in the sense that we all trusted that the One that the architecture, art, and liturgy pointed to would respond to our needs. I could hardly say the same about the many people I encountered at the Parthenon…as much as I once may have shared their desire to take corny pictures in front of the building.

Though markedly distinct from the Spanish baroque style, I felt that the other church styles had a similar effect on me…especially the French gothic churches. Similar to the pagan Greek buildings, the Gothic cathedral’s emphasis on verticality points one’s attention to God’s greatness and transcendence. And yet the darkness of the church interior allows for the mundane, the inconvenient, and ugly to enter the scene.

As sincere as our efforts to reach God may be, we must have a healthy sense of realism: we will never be able to reach him with our own devices. We remain in the darkness until His light, His divine wisdom, reaches down to us. The only sources of light in Gothic churches (before electricity was installed) was from the stained glass windows, which often depicted stories from Scripture or saints. In other words, the only way the navigate around this dark world is by following the Light shed upon us by God’s written and living Word.

The prevalence of gothic architecture in medieval monasteries indicates its usefulness for engendering an environment of contemplation and peace. God’s voice resounds quietly in the darkness, in the simplicity of everyday life…and this is only because God stepped into the darkness and lived an “everyday life” like us. Monastic leaders like Benedict of Nursia cultivated an entire lifestyle that centered around contemplation of God in prayer and offering one’s manual and intellectual labor to Him.

As I think back to the Parthenon, and the lack of awe and wonder in the faces of the people around me, I start to recognize how weak the ancients’ notion of strength and beauty actually are. At the end of the day, I’m never going to become an Adonis, an Apollo, or Athena, no matter how hard I try. Humans were never meant to reach perfection on their own. Dare I assert that this is why the formal practice of pagan religiosity is not nearly as widespread as Christianity thousands of years later? Even as secularism encroaches closer and closer upon Christian communities, its nuanced response to the distance between God’s perfection and human imperfection, its capacity to bind brokenness, uplift emptiness, and bring about unity still attracts people throughout the world.

The distant sight of the Areopagus reminded me that that experience of unity is possible even with these tasteless tourists. And so I walked down those slippery marble steps reciting: “Yet he is not far from each one of us, for ‘in him we live and move and have our being….”