I’ve been trying to keep up with the diverse array of responses to the release of “Man and Woman He Created Them,” the Vatican’s new document addressing gender theory and education. Predictably, liberal Catholic news outlets have criticized its lack of sensitivity to the trans community and conservative ones have praised its boldness in affirming traditional doctrine.

Outside of the world of Catholic media, several friends and acquaintances have expressed a sense of confusion. With their commitments to embracing both the truths taught by the Church as well as their transgender friends, they wanted to understand the document’s practical implications. Its language is highly abstract and intricate. The situations faced by people with gender dysphoria (GD) are very real and concrete. What is the document saying to those of us who live “on the ground”?

It might be helpful to point out that the document does not set out to condemn people with gender dysphoria. Rather, it intends to address the presentation of gender theory in educational institutions, a phenomenon which seems to be becoming more and more commonplace. Far from “attacking” any group of people, it calls into question the deeper anthropological implications of gender theory and offers a method of engaging in dialogue with current issues having to do with gender. The two-fold mission of the document is to help educators to best serve the young people entrusted to them by (1) calling them back to the truths of personhood while (2) encouraging openness to understanding contemporary culture.

The anthropological clarification offered is of great value. Much of the contemporary confusion regarding gender stems from a lack of a “clear and convincing anthropology that gives a meaningful foundation to sexuality and affectivity” (§30). Much of contemporary culture is enshrouded in a less-than-fully-formed view of what it means to be a person. Thus the confusion regarding gender applies to all “postmodern people,” not just those who experience GD.

Gender theory, along with most other postmodern forms of “theory,” is based on a markedly dualistic anthropology. The body is conceived to be separate from the will, and, accordingly, gender identity is not necessarily determined by biological sex. In this view, the will is afforded the agency to determine the person’s identity. The body, then, is “reduced to the status of inert matter” as the will “becomes an absolute that can manipulate the body as it pleases” (§22).

In a Christian anthropology, the person is an integral whole. Body and soul are not two separate entities but two dimensions of the one person, the former “giving flesh to” the latter (§22). The body reveals or speaks of the inner identity of the person . . . an identity which has been given her by the Creator (§24).

The dualistic anthropology characteristic of postmodern thought engenders a freedom without roots. It arises not from a relationship with a truth that precedes and defines the person, but instead concedes the person the freedom to construct truths of their own.

Alluring, surely, as it may seem, the document warns that this relativist notion of freedom gives rise to the illusion that “everything that exists is of equal value and at the same time undifferentiated, without any real order or purpose” (§20). Nothing is inherently meaningful, unless we arbitrarily decide to impose meaning on it.

In a recent article on gender theory, Abigail Favale attributes much of the contemporary discourse on gender to Judith Butler, the “godmother of contemporary gender theory.”

Butler argues, at least in her earlier works, that gender is an unconscious and socially compelled performance, a series of acts and behaviors that create the illusion of an essential identity of “man” and “woman.” In this view, gender is entirely a social construct, a complex fiction that we inherit and then repeatedly re-enact. . . .

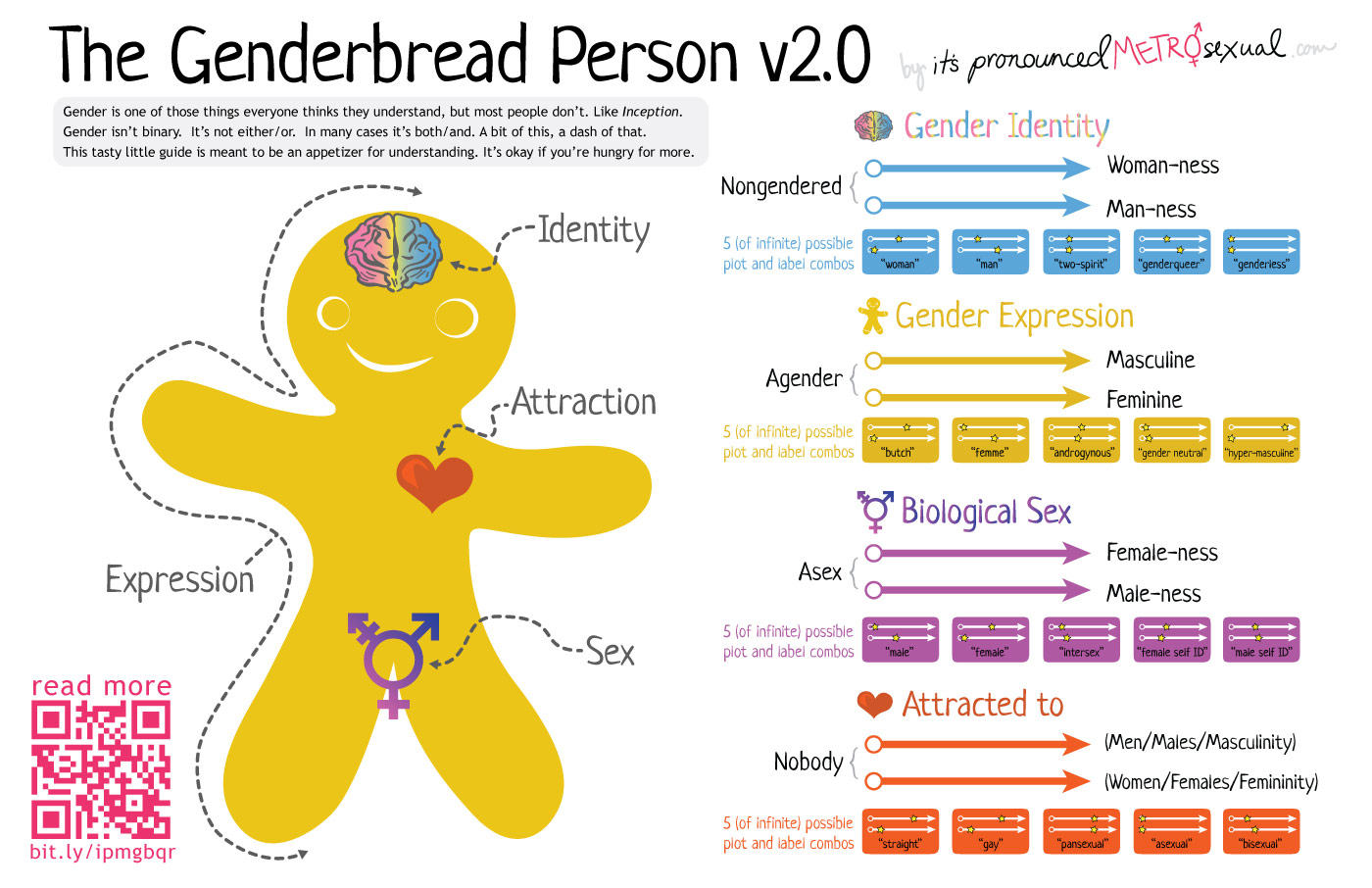

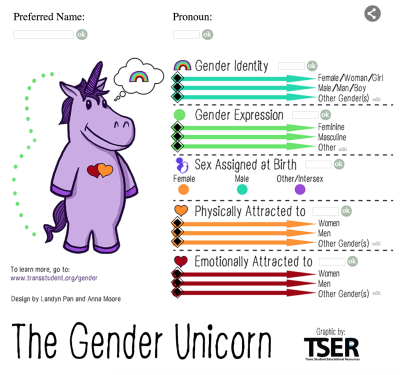

Even more recently we have the cute and overly complicated understanding of gender popularized by the “gender unicorn” and “genderbread person” memes. . . . In this model, personal identity is collated from a menu of attributes, each of which runs along a spectrum. Gender identity, à la the transgender definition above, is located in the mind; gender expression, a trickle-down version of Butlerian performativity, refers to one’s external appearance and acts; sex, which is “assigned” rather than recognized at birth, is confined between the legs.

Thus gender theory and the flawed anthropology that underlies it are the fruits of a much greater metaphysical crisis. Favale points to Charles Taylor’s 775-page tome A Secular Age to flesh out this overarching confusion about the relationship between material reality and the sacred.

Taylor characterizes the Axial Framework (in which Christianity, and to a lesser extent Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism, called the shots) by its “enchanted” view of the world. Physical objects, including our bodies, were thought to be charged with a spiritual meaning. The human body reflected God’s image and likeness, and was a vessel for carrying His life-giving love into the world.

In “the old framework . . . bodily sex referred to the person as a whole and was characterized by generative roles.” One’s identity as male or female was “not merely about external appearance, but also intimately connected to procreative function — one’s generative potential as a male or female.”

Contrary to Butler’s notion of gender as performance, being a man is not necessarily defined by the way one looks or acts. It’s about embracing a call, a purpose, which is inscribed into his soul and revealed through his body. Taylor would attribute this disconnect between the body and one’s “inner identity” to what he calls the “buffered self.” Stemming from a Cartesian separation between mind and matter, our identities are not molded by our experience in the material world. Matter is silenced — it no longer possesses the power to “speak” truths to us. Instead, it’s the duty of the mind to conform reality to its ideas.

This is why the document’s emphasis on getting our anthropology right is so important. We cannot begin to sort out contemporary concerns regarding gender without first establishing a clear understanding of the human person and her relationship with reality.

This is the first part of an article I previously published with Homiletic and Pastoral Review on “Male and Female He Created Them,” the Congregation for Catholic Education’s document on gender theory and education, which was published around this time last year. I will continue posting the subsequent parts of the article within this series.

Click here to read part 2 and 3.