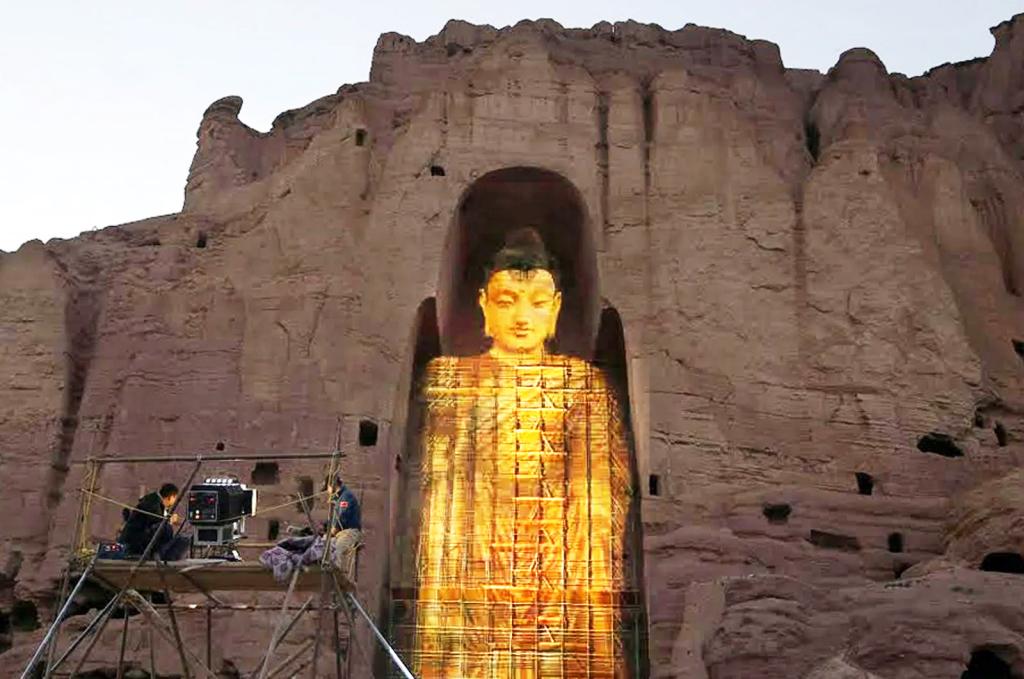

In July 1999, three years after the entry of the Taliban forces in Kabul, the group’s Minister of Culture stated that it was an absolute necessity to protect the cultural artifacts of the region. He even specified the two Buddha statues of Bamiyan, which the Taliban would only two years later infamously destroy.

The minister spoke about the respect due to those antiquities and also mentioned the risk of retaliation against mosques in Buddhist countries. He made it clear that, though he claimed there were no Buddhist believers in Afghanistan, ‘Bamiyan would not be destroyed but, on the contrary, protected’ according to Luke Harding (Guardian Unlimited, March 3, 2001).

Regardless, the Taliban leader, known as “Mullah Muhammad Omar,” declared that these were a “sanctuary for the kuffar,” claiming that said “kuffar” were “worshipping” these statues. This was, of course, a strange comment to make, since the Taliban had formerly stated that there were no Buddhists whatsoever in Afghanistan.

In March of 2001, both statues were destroyed by the Taliban following an order given on February 26, 2001, by Taliban Mullah, to destroy all the statues in Afghanistan “so that no one can worship or respect them in the future.”

The idea that Buddhists “worship” the Buddha or even “pray” to statues of the Buddha, is a product purely of the Western (and Near-Eastern) imagination. It is common today to hear ideas in Evangelical Christianity, common with those of Islamicate fundamentalism, stating that Buddha statues are “idols” which are prayed to as stone, wood or other deities. Nothing, of course, could be further from the truth – particularly in that Buddhism, perhaps more so than any other path, is against the illusion and delusions of materialism.

Buddha never claimed to be the Creator nor did he ask or instruct that he should be worshipped in any way or form. Indeed, the Dhammapada states unequivocally that “the Tathagata is only a Guide.”

The term Tathagata (तथागत) is Sanskrit in origin and is employed in the Pali text of the Buddha’s Dhammapada, to indicate one who has attained the highest goal. This term was used by the Buddha when referring to himself, in much the same third person sense that the Gospel protagonist speaks of himself as “the Son of Man” or literally “the Human Being,” as this is the meaning of the Hebrew “Ben Adam.”

The term is interpreted in Buddhism as meaning “one who has thus gone” tatha-gata, “one who has thus come” tatha-agata, or even “one who has thus not gone” tatha-agata (Anguttara Nikaya 4:23) – indicating that that the Tathagata is beyond all transitory phenomena of “coming” and “going” or “here” and “there” – or even incarnation and reincarnation. Outside of the illusion of Spacetime, the Tathagata is incarnate within each incarnation essentially in what would be classified in the material world as simultaneously.

That the Taliban and other Islamicate fundamentalists believe such a ridiculous idea about Buddhism and Buddha statues is unquestioned. But where on Earth did they get this idea?

Traditionally, Muslims have held a favorable opinion of Buddhists. We find numerous references to “al-Badadah,” meaning the Buddhists, in Classical Muslim literature. We also see references directly to “Al-Budd” – the Buddha himself.

Ibn al-Nadim (d. 998), records in his famous work entitled Al-Fihrist, many books, such as Kitab al-Budd that address Buddhism within a Muslim socio-religious context. Within his work, he delineates the different scholarly views of the Buddha: some believed he was the divine incarnate, while others claimed he was a prophet of Allah; still others thought Buddha to be a generic name for those who guided others onto the Straight Path – the Sirat al-Mustaqim.

Zhul Kifl: The Possessor of Kapila

The Meccan-born Indian scholar of Islamic theology as well the Urdu language, Abul Kalam Azad (1888 – 1958) in his Tafsir Surat al-Fatihah, noted that the Qur’anic prophet Zhul Kifl, should be understood as “the one from Kifl.”

Such a tafsir stood in stark contrast to the popular misconception that the Qur’anic figure was the Biblical Ezekiel. Indeed, the widely-utilized Yusuf Ali translation and commentary on 21:85 says: “Dhul-Kifl literally means ‘possessor of, or giving, a double requital or portion.'” Yusuf Ali goes on to note that “It is said that probably Dhul-Kifl is an Arabicized form of Ezekiel.”

The problem here is that Ezekiel, like all Biblical prophets, was already rendered into Arabic. We need look no further than the Arabic Bible, used by over 10,000,000 Arab Christians, to see that the name Ezekiel – an anglicized version of the Hebrew “Yechezqiel” (יחזקאל) – is “Heziqiyal” (حزقيال), in `Arabic. Azad was well aware the that Qur’an was referencing Guatama Siddharttha, the Buddha, when it said Zhul Kifl. He failed to note, however, that the prefixed Zhul is never utilized in the Qur’an in transliteration, but instead for what the word itself means: “possessor of.”

Had he mentioned this, his already correct thesis would have been strengthened. That is to say, just as the Qur’an uses the term Zhul Qarnayn, to reference Cyrus the Great (c. 600 – 530 BCE) – drawing on the Biblical reference to the “Two Horns” of the Medes and Persian empire, so too here is Zhul meant to refer to possessing a political region. In Qur’anic Arabic, the term “Zhul” is used exclusively to reference the ruling of a kingdom or kingdoms.

It is with this understand that this figure of Zhul Kifl, mentioned twice in the Quran (21:85 and 38,48) as patient and good, referred to Gautama Siddharttha. Although most normative scholars in the Muslim world identify Zhul Kifl with the Prophet Ezekiel, Azad explained that “Kifl” is the Arabicized form of Kapila, short for Kapila Vastu.

According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini, now in modern-day Nepal, and raised in Kapilavastu. The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown. It may have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, in present-day India, or Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal. Since the exact location of Kapila has been in dispute since before the days of Muhammad, it is obvious why the Qur’an would chose to refer to the Buddha as the ruler of this kingdom, rather than noting what would have been an updated geographical reference. As well, the name Kapila has clear etymological roots with the term Kapala, or “Head.” That is to say, the one who is master of the “Head” or “Kapala” could easily have been Qur’anically intended as a double entendre here as well.

By not getting overly specific and insisting on the listener accepting facts known to the orator about this figure or that, as doctrinal “Orthodoxy,” the Qur’an thus avoided creating pointless arguing amongst listeners about semantics that simply did not matter in terms of one’s practice and the work they were to do in making the world a better place and reducing suffering.

Those unfamiliar with Semitic linguistics should note that since there is no “p” in the `Arabic letters, words that would normally render with a “p” like “Palestine” or “Persia” are given an “Fa.” Indeed, in Hebrew, both P and F are written with the same base character. With that in mind, we thus have the same core consonantal letters of K-F-L or K-P-L for the name of this location of Zhul Kifl’s rule.

The popular notion that the name “Zhul Kifl” is an `Arabicized form of “Yechezqiel” (יחזקאל), is simply a lazy etymology. The core consonants are completely different from one another. There is, for instance, no qaf (ق) there is an extra lam (ل) there is a ka (ح) instead of a qaf (ق). There is absolutely no reason to imagine that this is the `Arabic form of Ezekiel, except uncritical acceptance of socio-religion norms of interpretation.

Gautama Siddharttha’s father was the ruler of Kapila Vastu, and the profound thing about the Buddha was in fact that he was offered anything his heart desired, but he rejected the Illusion or “Maya” of the physical world, in pursuit of the enlightenment which he indeed found beneath the Bodhi Fig Tree.

Azad was perhaps the most prominent modern mufassir exegete to voice such an interpretation, but he was far from the first. Imam Muhammad ibn `Abd al-Karlm al-Shahrastanl’s (d. 1153 CE) authored a comprehensive survey entitled, Al-Milal wa An-Nihal (Religions and Sects), the most celebrated and cited work on comparative religion in the pre-modern Islamic tradition. Within this work, Shahrastani also connected Siddhartha Buddha to the Qur’anic Zhul Kifl. So while such an assertion might sound strange, heterodox or even heretical to the Muslim Ummah today, this was clearly not always the case.

124,000 Prophets to All Nations

While normative Islam maintains hadith narrations stating there are as many as 124,000 prophets throughout the nations,[1] the vast majority of Muslims never stray outside of those delineated in the Qur’an, when it comes to who they personally consider a prophet.

The Qur’an, for its part, makes it clear that just because a prophet was mentioned in the Qur’an, this does not make them any less Prophets. To ensure that no one would be misled by the relatively short list of prophets named in the Qur’an, the following ayah was delivered, in order to drive the point home:

“And, indeed We have sent Messengers before you; of some of them We have related to you their story; and of some We have not related to you their story, and it was not given to any Messenger that he should bring a sign except by the permission of Allah. So, when the Commandment of Allah comes, the matter will be decided with Truth, and the followers of falsehood will then be lost” (40:78)

وَلَقَدْ أَرْسَلْنَا رُسُلًا مِّن قَبْلِكَ مِنْهُم مَّن قَصَصْنَا عَلَيْكَ وَمِنْهُم مَّن لَّمْ نَقْصُصْ عَلَيْكَ وَمَا كَانَ لِرَسُولٍ أَنْ يَأْتِيَ بِآيَةٍ إِلَّا بِإِذْنِ اللَّهِ فَإِذَا جَاء أَمْرُ اللَّهِ قُضِيَ بِالْحَقِّ وَخَسِرَ هُنَالِكَ الْمُبْطِلُونَ

“And We have mentioned Messengers to you before, and [there are] Messengers We have not mentioned to you – and to Moses Allah spoke directly” (4:164)

وَرُسُلاً قَدْ قَصَصْنَاهُمْ عَلَيْكَ مِن قَبْلُ وَرُسُلاً لَّمْ نَقْصُصْهُمْ عَلَيْكَ وَكَلَّمَ اللّهُ مُوسَى تَكْلِيمًا

While the Qur’an is clear that the absence of a prophet from the Qur’anic roster does not negate them as such, it nevertheless does mention the Buddha, by his royal position, as the prince, the ruler of Kapila Vastu.

“And Ismail, and Idris, and Zhul Kifl. All were of the steadfast” (21:85)

وَإِسْمَاعِيلَ وَإِدْرِيسَ وَذَا الْكِفْلِ كُلٌّ مِّنَ الصَّابِرِينَ

The exact site of ancient Kapila Vastu is today unknown. For centuries it has been theorized to have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, in present-day India, or Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal. This Ruler of Kifl, is mentioned by name twice in the Qur’an (21:85; 38:48).

The Bodhi Tree and the Surah of the Fig

Allusion is also made to the Buddha, in the ayat of the Fig Tree (95:1-5), beginning in the Surah or chapter of the Fig, At-Tin (التين), where it opens with an oath seemingly connecting the Fig to the Revelation at Sinai and the Olive to “this Faithful City.”[3]

It is widely know that the Buddha was said to have attained enlightenment at the foot of the Bodhi Tree (circa 500 BCE). Many outside of Buddhism, however, are unaware that the Bodhi Tree, also called the Bo tree, was a large sacred fig tree (Ficus religiosa) located in Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India.

Today, the Bodhi Tree has grown anew from a cutting of the original, at the Mahabodhi Temple. A shrine called Animisalocana cetiya was later erected on the spot where he sat. The spot was used as a shrine even in the Buddha’s lifetime. Emperor Ashoka paid homage to the Bodhi Tree and held an annual festival in its honor in the month of Kattika. His queen, Tissarakkha, was jealous of the tree, and in the nineteenth year of Ashoka’s reign, she is said to have killed it. Nevertheless, the tree grew again, and a monastery was attached to the Bodhimandha, called Bodhimanda Vihara.

It is said that every time the tree was destroyed, a new one was planted in the same place. This would, of course, be a perfect place to interject a midrash of sorts on the Gospel protagonist’s parable or mashal of the Fig Tree. Unfortunately, this would take as away from the topic at hand, and such a discussion must be reserved for another time.

With its heart-shaped leaves, the fig is good for health medicinally and food. The tree itself has a long lifespan of 900-1,500 years, sometimes as much as 3,000 years. In this way, much as the tortoise is employed in Taoist imagery for longevity and relative “immortality,” so too there seem to be allusion in the Buddhist (and Qur’anic) allegoric employment of the Fig.

Throughout history, the fig tree has always been a symbol of abundance and fertility. It is believed that the fig tree was in fact one of the first, if not the very first, plants to be cultivated by humankind. The historian Herodotos, living in the Mediterranean town of Bodrum, Turkey in the fifth century BCE stated that “fig culture is as old as human history.”

Indeed, figs have been with us since the dawn of human civilization, and may have even been integral to human evolution. According to ecologist Mike Shanahan, “The year-round presence of ripe figs would have helped sustain our early human ancestors and high-energy figs may have helped our ancestors to develop bigger brains. There is also a theory that suggests our hands evolved as tools for assessing which figs are soft, and therefore sweet and rich in energy.”

The sacred fig tree in Sri Lanka, known as Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi, is the oldest documented tree planted by humans. It was planted in 288 BCE by King Devanampiyatissa. The tree is said to have sprung from a branch of the original Bodhi Tree where the Buddha was said to have found Enlightenment.

King Ashoka’s Missions to North Africa and the Levant and the Judeo-Buddhist Therapeutae (Theraveda)

As I demonstrate in the work The Greatest Story NEVER Told: The Truth About the “Jesus” Myth and the Historical Figures Behind It, which some have referred to as my magnum opus, privately disseminated to direct Three Temples students,[3] there is clear and convincing historical documentation of the association with the Egyptian Therapeutae (Pali Indian: Theraveda) sect, with the small circle associated with the first iteration of the “Gospel” meta parable (originally: Sefer Basar Ha’Ruach).

Theravada (Pali, literally, the “School of the Elders”), is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism’s oldest existing school. The school’s adherents, termed Theravadins, have preserved their version of Gautama Buddha’s teaching or Buddha Dharma in the Pali Canon for over a millennium. The Theravada school descends from the Vibhajjavada, a division within the Sthavira nikaya, one of the two major orders that arose after the first schism in the Indian Buddhist community.

Theravada sources trace their tradition to the Third Buddhist council, when elder Moggaliputta-Tissa is said to have compiled the Kathavatthu, an important work which lays out the Vibhajjavada doctrinal position. Aided by patronage of Mauryan kings like Ashoka, this school spread throughout India and reached Sri Lanka through the efforts of missionary monks like Mahinda. In Sri Lanka, it became known as the Tambapaṇṇiya (and later as Mahaviharavasins) which was based at the Great Vihara (Mahavihara) in Anuradhapura (the ancient Sri Lankan capital).

According to Theravada sources, another one of the Ashokan missions was also sent to Suvannabhumi (The Golden Land). We know from the Indian Edicts of Ashoka engravings, that missionary dispatches were also sent to North Africa and the Levant, where they took hold and established schools and students.

The aforementioned Edicts of Ashoka record significant Buddhist missionary activity to the Mediterranean around 250 B.C.E. The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the pillars, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan Empire who reigned from 268 – 232 BCE. The inscriptions tell of Buddhist global missionary activity during that time period. Thus, we can clearly identify the Therapeutae as literally Judeo-Buddhist – in practice, diet and in beliefs – growing out of the Buddhist missionary activity in the Levant and North Africa that had been underway for several centuries, and had well-established Buddhism in the region by this time.

Conclusion

Having thus established the Qur’anic prophethood of the Buddha, we would be wise to return to the previous topic of “Resurrection” As Reincarnation in the Qur’an. That is to say, if the Buddha is regarded by the Qur’an and its orator Muhammad as being a prophet, then the idea that reincarnation is somehow in conflict with Muhammad’s teachings is simply illogical.

There can be no serious proposal that the Buddha did not in fact historically speak at length about the topic of reincarnation. With the accepted premise that he did, in fact, focus on such matters, this makes it clear that reincarnation is doctrinally “halaal” – or at least was regarded as such by the historical Muhammad. It is with that in mind that we might further contextualize the aforementioned passages on the Qiyammah or “Resurrection” within the Qur’an. That is to say, if the Qur’an speaks of Buddha as a prophet, knowing full well the focus of his teachings on ideas of karma and reincarnation, then it serves to reason those passages of the Qur’an which seem to speak about reincarnation more than reanimation of rotten corpses, might in fact most simply be explained as being just that: references to reincarnation.

Footnotes:

[1] Majlisi, Bihar al-Anwar, vol. 11, Hadith 21; hadith 21257 in Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal; hadith of Abu Dharr, et al. [2] The famous opening prophecy of Sefer Yeshayahu, the Book of Isaiah, excoriates the people of Jerusalem, previously renowned for their commitment to justice, had now become violent criminals, killing one another.“How did the Qiriah Ne’Emanah (קריה נאמנה) become a harlot? Justice rested there [as it was at home there]; but now they murder!” (1:21).

The Qur’anic reference, thus, to al-Balad al-Amin (الْبَلَدِ الْأَمِينِ), thus seems to be a clear reference to Jerusalem and the region or Bilad of Judea itself.

In future works, this passage will be discussed in relation to early Muslim mufassirun exegetes who claimed Muhammad orated the Qur’an not only in Mecca and Medina, but also in the Levant. It would seem the Qur’an is clearly alluding here to the connection between the Olive – or even “olive branch” – and Jerusalem, literally “the City of Peace.”

[3] Preliminary drafts of this enormous work were offered publicly, for a time. For a number of reasons, beyond the scope of the discussion at hand, I have decided against making this work publicly available. This is, in part, out of respect for the solidarity being shown by many in the Christian community, with the Jewish People, following the Hamas Pogrom of October 7th, 2023. As I believe this work cogently argues against the historicity many aspects of the Christian faith, I have opted to refrain from jeopardizing the faith of those amongst the nations who adhere to it – understanding that it may in fact lead them to do good, better the world and find personal comfort. Instead, I reserve this work and the conclusions of its research, for those who seek it out, rather than making it a public declaration against any particular premises of the Christian faith and its doctrines.In the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah, Laws of Kings and their Wars, 12:1, the great Jewish philosopher posits that in the Yamot Ha’Mashiach – the Messianic Era – all humanity will return to the true religion (yahzeru qulam la-dat ha-emet). He sees the Yamot Ha’Mashiach as a natural and not a miraculous event, Our Sages taught: “There will be no difference between the current age and the Messianic era except the emancipation from our subjugation to the gentile kingdoms.”

The Rambam certainly calls Christianity a “stumbling block” for the Jewish People, in that it has historically driven much antisemitism. “All the prophets spoke of Mashiach as the redeemer of Israel and their yeshua` liberator, who would gather their dispersed ones and strengthen their [observance of] the Mitzvot (Commandments of the Torah).” But “in contrast,” he notes, Christianity has “caused the Jews to be slain by the sword, their remnants to be scattered and humiliated, the Torah to be altered, and the majority of the world to err and serve a god other than Ha’Shem.”

This scathing critique notwithstanding, he notes that “nevertheless, the intent of the Creator of the world is not within the power of man to comprehend, for [to paraphrase Yeshayahu/Isaiah 55:8] Its ways are not our ways, nor are Its thoughts our thoughts.” And thus, the Rambam concludes that the literary character of Jesus of Nazareth and “that Ishmaelite” interestingly, refraining from calling this individual “Muhammad” in fact “only serve to pave the way for the coming of Mashiach and for the improvement of the entire world,” motivating the nations “to serve Ha’Shem together, as it is written [Zephaniah 3:9], “I will make the peoples pure of speech so that they will all call upon the Name of Ha’Shem and serve It with United As One – Shoulder-To-Shoulder in One Purpose (שכם אחד).”

He notes that this will come about by virtue of the fact that Christianity has spread throughout the world, and also the Muslim religion. “The entire world has already become filled with talk of Mashiach, as well as of the Torah and the Mitzvot. These matters have been spread among many spiritually insensitive nations, who discuss these matters as well as the Mitzvot of the Torah… When the true Mashiach Ha’Melekh arises and proves successful, exalted and uplifted, they will all return and realize that their ancestors endowed them with a false heritage; their prophets and ancestors cause them to err.” In that day, the Rambam explains, the errors will be made apparent without destroying their faiths but by excavating the truth beneath the generations of falsehood covered over it by their ancestors.

I have, accordingly, made it a habit when approached by missionaries, to tell them that I respect the good and charitable works that their faith motivates them towards, and that while I will be happy to engage them in a historical and Biblical discussion, I would advise them not to do so unless they are ready to seriously question their religion, and likely find their believe in it shattered. To date, all have thanked me and declined. As such, I leave it to the sincere seeker to come to me for this, should they desire. If not, then I wish them peace insofar as they wish the Jewish People peace.