The Book of Mormon begins by telling the story of a messianic figure named Nephi. The account appears in his own words and is immediately identified as the story of his “reign and ministry.” Nephi is therefore both “king” and “prophet,” two roles traditionally linked with ritual anointing and hence “messianisim” in the Bible. In terms of literary analysis, we might ask ourselves the question, “what is the purpose of this account?” If we read against the grain by questioning Nephi’s reliability as narrator, 1 Nephi has the feel of royal propaganda, to the point that all other characters (including his wicked brothers) almost feel like literary props.

Everyone, of course, writes for a reason. Nephi tells his readers that he wants to show them that “the tender mercies of the Lord are over all those whom he hath chosen, because of their faith, to make them mighty even unto the power of deliverance” (1 Ne 1:20). And while this statement democratizes divine tender mercies, the example Nephi chooses to illustrate this point is specifically his own life. He is the chosen one of God because of his faith. Nephi is the one that God made mighty.

The first adventure that Nephi shares about his own life reads like a classic folktale. Like all good folktales, it begins with a quest. The hero is sent on a journey to obtain a sacred treasure and in the process must slay the dragon, the ogre, the giant. Nephi presents himself as a faithful disciple of the clan’s leading prophetic figure, his father Lehi. Nephi opens the account stating that he was born of “goodly parents” in the plural, but then immediately treats his father as a single parent, “I was born of goodly parents, therefore, I was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father.” The word “somewhat” implies humility, but it’s directly countered by the inclusive “all.” Nephi is like the leading prophetic clan leader; he has learned his “language.”

The expression “my father” receives considerable emphasis throughout Nephi’s introduction. It appears ten times in 1 Nephi 1. In contrast, Lehi’s name occurs only three times in the initial chapter, and when it does, the name never appears without the additional descriptive, “my father.” The mere fact that Nephi repeats the phrase with so much frequency shows that Lehi looms as a pivotal figure in Nephi’s thoughts. But the term is even more significant. In ancient Israel, the expression “my father” was used as an honorific title for a leading prophetic figure (see, for example, 2 Kings 2:12). And Nephi describes himself as completely obedient to this man.

When Lehi sends Nephi on his quest to obtain the treasure, the commission not only illustrates Nephi’s complete fidelity to the man God had chosen to declare the divine word, it successfully disparages Nephi’s older brothers. The prophet declares:

Wherefore, the Lord hath commanded me that thou and they brothers should go unto the house of Laban, and seek the records, and bring them down hither into the wilderness. And now, behold they brothers murmur… Therefore, go, my son (1 Ne 3:4-6)

The imperative “go” appear repeated twice in the commission. And this repetition prepares us for Nephi’s acceptance: “Go my son, go my son,” and “I Nephi, said unto my father: I will go” (1 Ne 3:7).

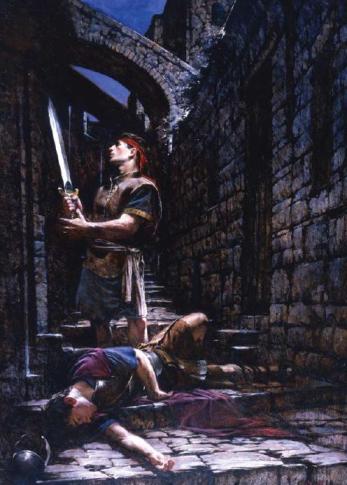

In a classic folktale, heroes are often helped along the way by animals (think Cinderella and the mice). And while we do see this motif in the Bible in stories like Elijah and the ravens, in most cases, the hero’s helper is a deity, the God of Israel. This is also true for Nephi and his quest. He specifically tells his readers “I was led by the Spirit, not knowing before hand the things which I should do” (1 Ne 4:6).

Of course the hero has to encounter an opponent to move the folktale plot forward: Sleeping Beauty has Maleficent, Snow White has the Wicked Queen. In the Bible, David has Saul, Moses has Pharaoh, Abraham has a famine, and Jacob, well, Jacob struggles against everyone. Jacob’s first opponent is his brother Esau, then it’s his Father-in-Law Laban, and eventually, Jacob even physically struggles against a divine being (Gen 32:22-32).

Nephi’s opponent is Laban, who happens to bear the same name as one of biblical Jacob’s opponents. Are we to understand by this that Nephi is like biblical Jacob, the patronymic ancestor whose name is eventually changed to Israel and who therefore personifies God’s covenant people? Perhaps. Either way, Nephi’s account is a classic folktale.

Like all good folk heroes, Nephi experiences a transformation during his quest. In a traditional folktale, heroes are typically branded or marked in some way during the course of their journey. A change might happen, for example, where a girl in rags transitions into a beautiful woman or a frog becomes a prince. We find similar motifs in the stories of Genesis. Abraham is sent on a quest to find a promised land and is circumcised along the way. Later in Genesis, Abraham’s grandson Jacob is sent on a quest to find a wife. During the adventure, Jacob wrestles with a divine being who dislocates Jacob’s thigh. Like all classic folk heroes, Jacob is physically changed. From that point forward, he walks with a limp. His struggle, therefore, is something Jacob will always carry, like the mark of Cain (which also fits the folktale pattern). Even Moses is physically changed following his encounter with God. In Exodus 34, we learn that after this “wrestle,” Moses must wear a veil because his face shines. As a classic folktale hero, Moses too is therefore branded or marked during the course of his journey.

Nephi is also changed. After he slays the might man and obtains the treasure, he appears vested in armor, a symbol of his victory and ability to fulfill the traditional role of a king by leading the troops into battle. This change is also highlighted by Nephi’s use of the traditional Near Eastern battle cry “be strong” (1 Ne 4:2). In the Bible, the phrase “be strong” is specifically used in military orations and exhortations. Nephi has become the mighty man. He kills the villain, wears the armor, and successfully leads the frightened troops (his brothers) on their sacred quest.

After this change (symbolized by the armor), Nephi assumes the role of a suzerain with the power to offer a treaty to Laban’s servant. Unlike a royal grant, a suzerain treaty between high king and vassal carried stipulations. Nephi is a “man large in stature” who is able to “seize the servant” and offer a “royal” treaty:

I spake with him, that if he would hearken unto my words, as the Lord liveth, and as I live, even so that if he would hearken unto our words, we would spare his life. And I spake unto him, even with an oath, that he need not fear; that he should be a free man like unto us if he would go down in the wilderness with us (1 Ne 4:32-33).

It’s probably not a coincidence that until he accepts this treaty, the servant is never named. Nephi simply refers to him as “the servant of Laban.” But after he accepts this oath, the servant is given a name in the account, Zoram. The treaty theme reappears later in the Book of Mormon when at the end of his life, the prophetic clan leader declares:

Zoram, I speak unto you: Behold, thou art the servant of Laban; nevertheless, thou has been brought out of the land of Jerusalem, and I know that thou art a true friend unto my son, Nephi, forever. Wherefore, because thou hast been faithful thy seed shall be blessed with his seed, that they dwell in prosperity long upon the face of this land; and nothing, save it shall be iniquity among them, shall harm or disturb their prosperity unto the face of the land. Wherefore, if ye shall keep the commandments of the Lord, the Lord hath consecrated this land for the security of thy seed with the seed of my son (2 Ne 1:31-32).

And this is classic vassal treaty imagery. Nephi is the king who leads the troops into battle, slays the villain and as suzerain offers a vassal treaty to Zoram, all of which prepares us for Nephi’s “reign.” But through this exchange, readers are also prepared for Nephi’s “ministry” by a close reading. At the beginning of the account, Nephi’s language appears linked with Lehi’s language, so there’s a literary progression from prophet to deity. Here Nephi’s words are connected with God’s words:

If he would hearken unto my words,

as the Lord liveth, and as I live,

If he would hearken unto our words,

we would spare his life.

Nephi begins the statement with an admonition to “hearken” (a powerful term meaning listen and obey) unto “my words,” and then transitions the hearkening to “our words.” The statement begins with a first person pronoun, which then moves to a plural.

Grammatically, the antecedent for the plural pronoun is Nephi and the Lord. Yet contextually, the pronoun seems to allude to Nephi and his brothers. Nephi follows this statement with reference to his father and the fact that Laban’s servant would have place “with us.” Hence, there is a grammatical reading which identifies the plural as Nephi and the Lord, and a contextual reading which identifies the plural as Nephi and his family. The ambiguity between grammatical versus contextual meaning effectively obscures Nephi’s prophetic role. We know that God speaks to him, but Nephi is not yet ready to speak God’s word to others. That role belongs to his father, Lehi, which is perhaps why Nephi’s narrative begins with an account of Lehi’s throne theophany and prophetic commission. Nephi is not yet king, nor is he prophet, but by the time readers have finished this opening folktale, we have no doubt that he will assume both messianic roles.

In fact, as great a prophetic figure as Lehi is in Nephi’s account, Nephi himself is greater. He’s completely obedient to his father to the point that he only grammatically connects his words with God’s words in the opening story, but there’s little doubt who the more powerful figure is. Lehi complains in the wilderness, but Nephi turns to God and finds food. Lehi has an incredible vision of a tree of life, but Nephi’s version completes it. Nephi is the one who receives the vision to build the boat and he is the one who successfully does so.

This family will eventually be divided into two groups. Nephi is the fourth son. It’s therefore natural for readers to assume that one of his older brothers should rightfully lead the familial clan after Lehi’s death. So in terms of genre, Nephi’s account is propaganda. It makes clear the Lord’s tender mercies were upon Nephi more than any other member in the family, including Lehi himself. Nephi was God’s chosen, the one God made mighty even unto the power of deliverance, the one who combines two traditional messianic roles as prophet and king. Not even Lehi did that.