Proper 12 — Year C — Luke 11:1-13

There is no war on poverty in this country. There is no war on hunger.

Instead, there is a war on the poor and a war on the hungry.

Politicians today are targeting and bargaining away the food on the tables of the poor in the name of fiscal responsibility. For the first time since the 1970s, there is no funding for food stamps (Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program) in the broad, bipartisan farm bill. House Republicans have passed a bill gutting food stamps (SNAP, or Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program) for those in need in our country. Many Republicans have not minced words about their disdain for the food stamp program and the people who use it and support it.

In short, they have demonized anyone who asks for help. In doing so, they have tapped into a potent American narrative that champions self-sufficiency and individualism and characterizes the need for help as a flaw in one’s moral fiber. We live in a culture that considers it shameful to need help, shameful not to be able to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and work our way out of need. We value the fences that make good neighbors — the fences of self-sufficiency — as if we could construct our lives to where we don’t need anyone else.

What our culture values is independence and the freedom to be free from our obligations to each other, our neighbors and the world. It values the kind of work ethic that makes asking for help a moral failing. We believe if we put our head down and work hard enough for long enough and save our money, we will never need to face the shame of asking for others help.

In our country, our entire social safety net, our nation’s system of helping our neighbors, doubles as a process of shaming. If you have ever applied for food stamps, unemployment, or welfare, you likely know what I’m talking about.

Depending on the program, you are often required to catalogue all the ways in which you do not have enough to survive — to feed your family or to provide them with basic shelter, or electricity, or running water. Or, it requires you to list all the ways in which you have failed at gainful employment — and to check back in periodically to report all your unsuccessful attempts at employment. You are interviewed, questioned, and required to detail every asset you have.

The entire process sends one message to the applicant, and it isn’t a message of hope or of help. It is a message of shame. It says, “You have failed at being a productive member of society.”

And this process, of course, says nothing of the stereotypes some of us have and often perpetuate in our daily lives and our conversations.

Does someone need unemployment? They must not want to work.

Does someone need food stamps? They must be lazy.

Does someone need welfare? They are on the government dole, taking money from the hard working folks who don’t need help.

We call them names like welfare queens, or worse.

We shame them.

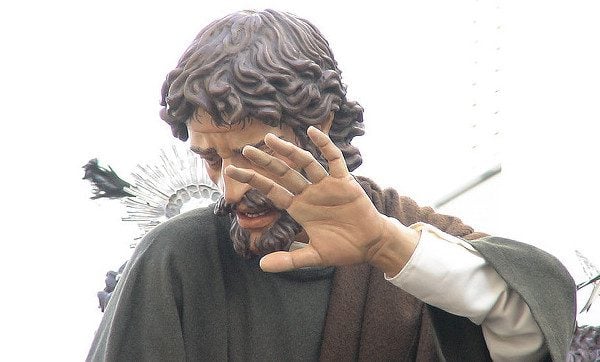

But in our gospel text today, shame isn’t directed at the one in need, the one who asks for help.

Rather, the shame is directed at the one who refuses to help.

The parable we read today is typically called the Parable of the Persistent Neighbor. But honestly, how persistent is this neighbor? He asks for help only once. He knocks only once. This isn’t exactly the model of persistence.

Many biblical scholars agree that the we’ve mistranslated this word in the story, for it more accurately indicates shame instead of persistence. And given the cultural context, a neighbor asking for help to show hospitality to guest wouldn’t have been the least bit shameful. But refusing to help most certainly would. We might do better to think of this instead, then, as the Parable of the Shameful Sleeping Neighbor.

In fact, asking for help from the village in order to put the best food on the table for a guest would have been expected. And more importantly, it would have been an honor to be asked to help provide. And when a visitor arrived to a village, it was an event. So the whole village pulled together to provide the best food in the village for the guest. It was a matter of honor not just for the individual host but a matter of honor for the entire community.

So one can only imagine the shock dealt to Jesus’ audience when the sleeping neighbor refuses to help. It is the equivalent of withdrawing from the village and outright rejecting one’s friends who have provided bread for you during times of your own need.

It is the equivalent today of saying, “I am an island. I will pull myself up by my bootstraps.”

But Jesus indicates this behavior is indeed shameful. And it is the shame, felt by the sleeping neighbor, not the in-need neighbor’s persistence that eventually fulfills the request for bread.

This all makes sense, of course, in the context of how Jesus teaches his disciples to pray, both in today’s gospel and elsewhere. If you notice, the prayer we say every Sunday is a communal prayer, not an individual one. It is, after all, the final prayer we say together before we rise to communion together and with God in the Eucharist.

Teach us to pray. Us. Give us daily bread. Us. Forgive us. Us.

Bread is not something made in isolation. It takes farmers, field workers, millers, markets, and bakers to provide it. Even our forgiveness, in the Lord’s Prayer, is tied to community. Forgiveness is not possible, it seems, if we ourselves cannot forgive others.

This isn’t an individual prayer. It is one that involves us all in relationship, in the kingdom of God. And in God’s kingdom, we are fed, together. We are forgiven, together. We are saved, together.

And if one of God’s beloved children does not have their daily bread, we are not truly fed, either. Then, we too should feel hungry. Hunger anywhere is hunger everywhere, particularly in a country that sings of its amber waves of grain.

Many of our churches work hard to feed the hungry and to help the poor. They give of their own time and their own limited paychecks to make sure others can eat. They grow gardens only to give its fresh produce away.

Yet in our paradoxical time of plenty and of food insecurity and hunger, where in our county between a quarter and a third of its citizens don’t have enough to eat, private donations alone from us and from other churches combined won’t be enough to feed those in need. Thankfully, there are government programs that fill in many of these understandable gaps in our care.

Yet, there is a prevailing story I hear told from our culture and our media about people who need help, who rely on food stamps or soup kitchens to fight off hunger for themselves and their children. I’m sure you’ve heard it, too. This narrative says that these people are lazy or degenerates, mooching off the government and the hard work of others.

It is a horrible lie. The majority of those using food stamps are the working poor, are children, or are over the age of 60. More white people than any other group, and a food stamp recipient is more likely to live in a rural part of the country than an urban one. In South Carolina alone, more than 100,000 households use food stamps each month to get the food they need to prevent hunger. The average benefit per person in South Carolina comes out to $4.37 a day. In other words, that apple a day that keeps the doctor away might just eat up almost a quarter of your food budget for the day.

Now as Americans, we are welcome to believe and argue about these programs aiding the hungry and the poor. We can debate about how best to administer them. As Americans, we can even call for their complete dismantling.

But we cannot as Christians. Now, I know we don’t live in a system without its flaws. Yet as a people whose primary ritual is a feast — the Eucharist, we might want to think carefully about how we characterize the hungry, those who knock on our doors asking for bread. We must always remember what our Savior says — that whenever we see a hungry person, that person is Christ himself. So if we want to look for God in this parable, we shouldn’t look at the neighbor who finally gives up the loaves of bread as a bad approximation of how God answers prayers. Rather, in this parable, God is the one who comes to us at inconvenient times asking for help. God comes to us disguised as the hungry and poor and invites us to be a part of God’s kingdom of radical hospitality and generosity.

So, as a Christian, I rejoice with the hungry and starving Christ is fed, whether through my tax dollars, my charitable contributions, or through my own two hands. Because the truth of the matter is, there is enough hunger and systemic poverty in our world that we need an all-of-the-above approach, not an ideological either-or stand. See just because someone uses food stamps or the soup kitchen, it doesn’t mean they are lazy. It means they are hungry. Just because someone uses programs like welfare or Catholic Social Services, it doesn’t mean they are degenerate deadbeats. It means they need help and they are asking the only neighbors they have for it.

Not long ago, my son and I were having one of those parent-child stand-offs about bedtime. He had taken the position that he wasn’t going to sleep. I had taken the position that he was.

I thought it was most important in that moment for him to learn a lesson about personal responsibility and about following the rules of bedtime.

He thought it differently, and he began to cry. With tear-stained cheeks he said, “But you are my daddy, and it is your job to give me what I need, and I need a cuddle because it is dark and I’m scared.”

That night, I sat in bed with him until he fell asleep. But, much like the sleepy neighbor, it was a sense of shame that got me up to cuddle with him. I wish I could say it was a sense of being honored to help.

As I sat there with him, I thought about all the times in our world when our brothers and sisters have asked for help, have been scared that they wouldn’t make it through the night, the next day, the coming week. I thought about how many people sleep restlessly as their stomachs rumble wondering where their next meal, their next roof, their next paycheck to keep the electricity on will come from.

I wondered how many of them have asked for help for what they need and felt shamed for it.

I wondered how many of us might have shamed them for it, whether directly or indirectly.

I wondered how many of us have been the sleeping neighbor, and when we hear the cry for help, we bolt our doors and explain we are just too comfortable to get out of our warm beds.

And then I wondered what it would be like to live in a culture like Jesus did, where the shameful behavior wouldn’t be the asking for help, but the refusal to help when asked.

What it would be like to live in a world where it was an honor, not an inconvenience, for a neighbor to ask you for bread?

It would be a lot like the kingdom of God, I suppose.

May our prayer be the prayer of Jesus. Father, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Give us each day our daily bread. And forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive everyone indebted to us. Do not bring us to the time of trial.

Amen.

__

Sources:

William R. Herzog, II. Parables as Subversive Speech: Jesus as Pedagogue of the Oppressed