G.K. Chesterton once wrote that a person who relied entirely on his own spiritual resources, was like a man who sucked his own thumb in order to derive nourishment. Obviously we have to look outside of ourselves to find our true “food”. Our eternal sustenance comes from an eternal Source; the immediate question is: how do we cultivate and ingest that “immortal manna”?

G.K. Chesterton once wrote that a person who relied entirely on his own spiritual resources, was like a man who sucked his own thumb in order to derive nourishment. Obviously we have to look outside of ourselves to find our true “food”. Our eternal sustenance comes from an eternal Source; the immediate question is: how do we cultivate and ingest that “immortal manna”?

We human beings tend to make a great pother and to-do about getting close to God, as though He were a duchess in the Celestial Court, far above our rank, and only the most erudite and earnest solicitations on our part would bear any chance of success. Most of the religions of the world treat the highest divinities like this: they must be approached through a long series of kowtows and genuflections and ablutions, while they’re serenaded with the most fulsome addresses, and appeased (one hopes) with extraordinary acts of sacrifice and charity.

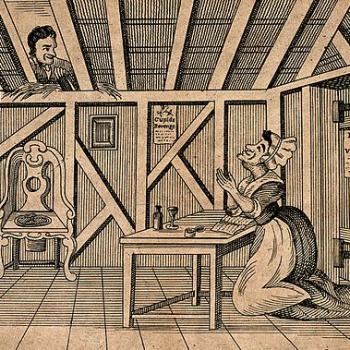

Madame Guyon had a very different insight into the matter. In about 1685 the Frenchwoman produced a slim volume called A Short and Very Easy Method of Prayer. In it she rhapsodized about the ecstasies of simply giving oneself to God – that’s her method (a bit different from John Wesley’s famous method, which evolved into Methodism), and that’s how uncomplicated it is. Here is one of her charming descriptions of the process, and note how seductive the imagery is:

If you want to reach the sea, set sail on a river and you will be taken to it gradually and without effort. If you want to go to God, follow this sweet and simple path and you will arrive at Him with an ease and swiftness that will amaze you.

I don’t want to leave you with the impression that Madame Guyon is unaware of the necessity for renouncing one’s sins in this process, or that she is ignorant of the struggles of the flesh and the hazards of repeated backslidings. All these elements of the Christian life she tackles in her own winsome and unexpectedly subtle fashion. Yet it is her gift for poetry that makes the greatest impact – that is to say, her ability to find une image juste. Here, for example, she nails with lyrical precision the gist of her simple, natural, and “very easy” procedure:

Now what happens to the baby who gently and without effort drinks in the milk [at its mother’s breast]? Who would believe that it could so easily receive nourishment? Yet the more peacefully it feeds, the better it thrives.

Like all mystics Madame Guyon often loses herself in vague and maddeningly unspecified byways, and like mystics of any religion she will many times confuse agape with eros. When she maintains that the soul after death has to lose all of its self in order to be united with God, she seems to forget that each of us is unique, and that we cannot be unique without that which makes us unique: those very particulars that make up the self. Madame Guyon would answer that “the strong and universal light [of God] absorbs all the little distinct lights of the soul, and they grow faint and disappear under the powerful influence of God’s light…”

Yes. To a degree. But if we all grow indistinct and indistinguishable, then we all grow (to a certain extent) fungible. And I don’t find that to be the way the Great Shepherd views His individual lost sheep, whom He calls by name. Our authoress, who died in 1717, and who was imprisoned for years by the ecclesiastical authorities for advocating such a non-ecclesiastical path to the Father, is nevertheless a heroine (if not a duchess) in the Celestial Court where she now resides. She’s a heroine for reminding us – as all reformers do – that the Father is always as close as a half-articulate whisper. Or a tearful sigh. Like an aged mother whose grown children have deserted her, God spends His time waiting by the phone, wishing we would call.