Can Technology Prevent the Harms Previously Prevented by Religion?

In my last post I asserted that religion was a form of technology: a way of packaging the beneficial behaviors that have emerged from cultural evolution and passing them forward in time. With this as a starting point, the question becomes “what happens when this old technology clashes with our new technology?”

Clearly, an example is in order. In the last post we talked about the technology of monogamous marriage. This is an old technology, embedded in nearly all major religions, and many people continue to defend its utility. Other people think that it is no longer important, that whatever utility it provided can now be found elsewhere, and the downsides it protected against can be mitigated.

Up until very recently, from a historical perspective, sex could easily result in pregnancy. As such, many traditions and taboos required that either you didn’t have sex before marriage, or if you did, and it resulted in a pregnancy, that marriage soon followed. But some people claim that because of new technology this is no longer a problem: we have access to a wide variety of birth control — most notably the pill — and if that fails then there’s always the option of getting an abortion.

Alternatively, another purpose of marriage and its associated monogamy could have been to prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Truly monogamous people can’t transmit STDs. But these days we have latex condoms which are great (but not perfect) at preventing the spread of such diseases, and should that line of protection fail we have antibiotics and other tools of modern medicine.

These developments, in tandem with a push towards greater freedom and autonomy, led many to argue that traditional marriage and other sexual taboos were outdated. These developments ushered in a revolution against these traditions and taboos — a sexual revolution. This revolution did not entirely overthrow the old regime, there are still places where it clings to power, but this ideology of sexual liberation is very much the dominant one in the western world for the moment.

Does the New Technology Provide All the Benefits of the Old?

On the other side of the coin, if marriage and its associated taboos prevented certain harms then they very likely provided some benefits as well. These benefits didn’t receive much, if any attention during the revolution, but now that we’re 50 years down the road they’re becoming more and more apparent.

Of course some benefits were always apparent. It’s been clear for a long time that having two parents is better for children, but even in this case more attention was paid to the harms. In particular the harm of forcing people to stay in unhappy marriages.

If you squint there were some attempts to replicate these benefits as divorce rates skyrocketed. Things like child support, and an increase in certain forms of welfare. Still, it’s clear that not only was there less attention paid to the benefits of marriage, but that these benefits were more difficult to quantify and duplicate.

Nevertheless, on the balance most people seemed to think that the tradeoff was a good one. Most of the really large harms associated with declining marriage rates and increasing promiscuity could be mitigated by technological advances or progress by governments and the like, without forcing people to stay married. Things like easy and efficacious birth control combined with a sufficiently robust social safety net. This wouldn’t cover all of the harms and lost benefits, but what it cover didn’t seemed minor in comparison to the large benefits we received from the greater freedom under the new regime. For most people this appeared to be progress. We had moved to a better place.

How Are We To Know When Traditions Can Be Abandoned?

But in order for all of this to be true we would need to have identified all the harms that were being prevented and all the benefits we were foregoing. If we overlooked any of these, perhaps because they were less obvious, then this assessment might not be true. We could have inadvertently ended up in a worse place without realizing it. In order to illustrate how difficult this identification can be let’s consider an example. What follows is a long quote form the The Secret of Our Success by Joseph Henrich:

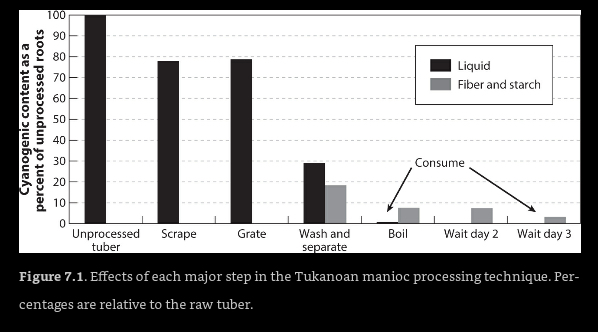

In the Americas, where manioc was first domesticated, societies who have relied on bitter varieties for thousands of years show no evidence of chronic cyanide poisoning. In the Colombian Amazon, for example, indigenous Tukanoans use a multistep, multiday processing technique that involves scraping, grating, and finally washing the roots in order to separate the fiber, starch, and liquid. Once separated, the liquid is boiled into a beverage, but the fiber and starch must then sit for two more days, when they can then be baked and eaten. Figure 7.1 shows the percentage of cyanogenic content in the liquid, fiber, and starch remaining through each major step in this processing.

So all of these steps are necessary to make the manioc — also known as cassava — safe to eat. How on earth did they arrive at this process? Through long term cultural evolution, as discussed in my last post. Using the term “religious” very broadly you could say they have a religious ritual around manioc preparation.

Let’s suppose that a well-meaning reformer came along. Someone who can’t test for cyanide, who only knows that people are spending a lot of time on manioc preparation — time that might be better spent elsewhere. As it turns out, manioc, particularly the varieties high in cyanide, is very bitter. If you do everything on the figure above up through boiling, then it is no longer bitter, and you also prevent all of the acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, stomach troubles, and vomiting). But a significant amount of cyanide would still remain.

Returning to Henrich:

So, if one did the common-sense thing and just boiled the high-cyanogenic manioc, everything would seem fine. Since the multistep task of processing manioc is long, arduous, and boring, sticking with it is certainly non-intuitive. Tukanoan women spend about a quarter of their day detoxifying manioc, so this is a costly technique in the short term. Now consider what might result if a self-reliant Tukanoan mother decided to drop any seemingly unnecessary steps from the processing of her bitter manioc. She might critically examine the procedure handed down to her from earlier generations and conclude that the goal of the procedure is to remove the bitter taste. She might then experiment with alternative procedures by dropping some of the more labor-intensive or time-consuming steps. She’d find that with a shorter and much less labor-intensive process, she could remove the bitter taste. Adopting this easier protocol, she would have more time for other activities, like caring for her children. Of course, years or decades later her family would begin to develop the symptoms of chronic cyanide poisoning.

Accordingly, something that seemed like a waste of time, a needless addition that didn’t do anything, ends up being critical once you look at things from a long enough time horizon. What seemed pointless was very important.

Are We Slowly Being (Metaphorically) Poisoned?

There are many possible lessons one can take from the example of the manioc. One that seems particularly relevant at this moment, is the significant amount of time it can take before the true harms of abandoning a tradition manifest themselves. Beyond that, when many things have changed during that period, there is a further lesson about the difficulties which attend making a connection. How are we to know which of the many things we have abandoned in the name of progress have led to the harms we now experience?

I have talked a lot about the diminishment of marriage and the removal of sexual taboos, but over the last several decades we have made numerous changes besides these, and all to fundamental aspects of our lives. Accordingly, to the extent that you feel that things have gone off the rails there could be any number of causes. It could be that there’s one big cause which is easy to fix, or it could be that many of the changes are operating together.

It could be the loss of community Robert Putnam described in Bowling Alone. It could be the alteration of sexual norms described by Louise Perry in her book The Case Against the Sexual Revolution. It could be the deleterious effects of TV as described by Neil Postman in Amusing Ourselves to Death. In every case, whether it’s the lack of community Putnam describes or the banality Postman warns of, these things could have been mitigated with a greater focus on the old technology of religion. (Perhaps you’re having trouble making the Postman connection? Christianity isn’t focused on the good book for nothing.)

Despite all of the foregoing, perhaps you’re one of those who think things are going great. And here we turn to another lesson provided by the manioc. Technology’s power to reduce harm is justly celebrated. Metaphorically we’re still processing manioc, but we’re doing it in new and better ways! These days, if we turn our minds to something like removing bitterness, and reducing visible harms, we generally do a great job. Our metaphorical manioc is entirely free of bitterness, we may have even added sugar to make it really tasty.

But it’s always possible that in our focus on the clear and immediate harms, we have missed the cyanide still lurking in the heart of the manioc. That the traditions, taboos, and religions of those who preceded us contained unrecognized wisdom — wisdom we have overlooked in our diagnosis of the world’s ills. Consequently we have misdiagnosed the problem, and treated the wrong ailment, and it’s only now that our true disease emerges and our chronic poisoning makes itself felt.

Are we then without hope? For those with faith there is always hope, but concrete recommendations are also helpful. We’ll get into that next week.

If you would prefer to listen to this post you can find an audio version here.