A long time ago in the big city, I was a graduate student studying the New Testament. My wife and I had another student and his wife over for supper, and we were talking shop: Bible and theology, church and history. Our friends were these passionate Presbyterians, and I was saying something judicious about finding the idea of ministry attractive, when he said to me, “So why don’t you go into ministry?”

“Because I’m not called,” I demurred.

“So get called!” he said.

I did, eventually, get called, though maybe not in the way he–or I–imagined. At that point in my life, I thought a calling to ministry would involve a vision or a voice, some sort of unmistakable and stern word from God: Go into ministry! Now! (The application deadline for seminary is May 15.) I figured a calling should be something prophetic–if not a Damascus Road or a burning bush, then at least a fire in the bones. I wanted something eerie and other. And I have had a couple of those take-off-your-sandals-you’re-on-holy-ground moments, times when a fire flared in my bones and in my belly. I’ve heard the strong word, the resonant word, the deep word that rumbles dreams. But my calling to pastoral ministry has mostly unfolded out of my Christian faith. For me, being called to ministry has felt like living out my faith, an extension of being called to Christ. I heard my ministerial calling by hearing my baptismal calling.

More than a feeling: Internal and external calling

I suspect many of us are carrying around a flawed understanding of what it means to be called. We go heavy on the subjective experience of feeling called, feeling led, feeling like we’ve found our niche. Sometimes we label this feeling an “internal call.” It’s an attractive notion: God has laid something on our hearts, something special, and only we can feel it or know it.

Yet emphasis on an internal calling can go wickedly awry. While an internal sense of calling can sometimes serve as a powerful compass through ministerial storms, it can also be a way to arm-twist individuals and congregations. It goes something like this: I’m called. Listen to me, or get out of my way. Nevermind that there was only one person of whom God said, “This is my Beloved, my Chosen, listen to him” (Luke 9:35-36).

I’ve bumped into people who claim a profound internal sense of calling. The humblest among them inspire the most trust in me. They’re circumspect in describing their calling. They labor away in obscurity. They face despair. They wonder if they’re doing anything that matters. Their sense of calling is sprinkled with a dash of doubt. These folks draw me in to their stories, like the wise pastor I once met who described how God kept showing up beside him in the church pew, nudging him and asking, Can you imagine yourself up there behind the pulpit? To which, over the course of several years, he consistently responded, No, I can’t.

But I’ve also encountered people who are so sure of themselves and their internal calling that they reject any advice or oversight by the larger church. They’re eager to claim the prophet’s shaggy mantle and hit the streets. These people make me nervous. I ran into a man once who claimed a pastoral call. He didn’t need training or discernment or recognition. He had his call. So he carved a chunk of people off from the congregation he belonged to at the time and set up shop across town, leaving his former congregation and pastor bewildered and hurt.

I wonder if in many churches, we’ve placed too much weight on the subjective, internal call. It strikes me that the concept of the internal call stands in tension with much of the biblical vision of ministry.

In the Old Testament, the sons of Aaron were chosen to be priests (see Numbers 18). The priestly ministry flowed from God’s original choosing of the Levites. The priest’s service was not dependent on how he felt about it. The work of the priesthood was a gift that came from God (Num. 18:7). When some Israelites, led by Korah, felt that they too should be able to serve as priests, despite not belonging to the Levitical line, the earth swallowed them whole (Numbers 16:3, 32). Afterwards, God again established that it was he who had called Aaron by making Aaron’s rod bud forth in almonds (Numbers 17:1-7). God did the calling, and it was rather objective and external.

In the New Testament, we see something similar in Timothy’s calling. Paul speaks of Timothy’s capacity for ministry as a “gift” that he received from the church elders through the “laying on of hands” (1 Tim. 4:14; 2 Tim. 1:6). Paul says Timothy was “called” to faith (1 Tim. 6:20) and “called” to the Christian life (2 Tim. 1:9), but as far as I can tell, Paul doesn’t speak of Timothy as “called” to ministry.

Paul himself, who was famously called into the apostolic ministry on that road to Damascus, spent three years in the deserts of Arabia testing the meaning of his call (Galatians 1:15-18) before going up to Jerusalem to compare notes with the already established apostles. His calling was reaffirmed by the church in Antioch, when in a time of fasting and worship, the Holy Spirit told them to set apart Saul and Barnabas for the Lord’s work (Acts 13:2).

So if we need to rethink what it means to be called, what does this look like in the contemporary church? Here are three possibilities:

1.) I wonder if we need to move away from our reliance on a felt sense of God’s calling. Those with tender consciences are rarely called in this scenario. They’re often sidelined by those more confident of their own ability to hear God. Instead, I suspect we need to rely more deeply on the church’s discernment. Put less weight on the individual’s inner calling and more emphasis on the church’s outer calling out. Perhaps the preeminent characteristic we should look for in ministers is not a felt sense of calling, but a willingness to respond to the church’s need and submit to the church’s wisdom.

2.) We need to back away from a sense that the calling to ministry is something eerie and other. Ministry isn’t eerie and other; why would the calling to ministry be? How many people are waiting to be plucked from their mundane lives and sent out on the Lord’s errand? They want to be struck from above when what they really need is to look for ways to serve God and God’s people right in front of them, in the church.

3.) Above all, we need to remember that God’s calling of some to ministry is an extension of God’s calling of all his people in baptism (Ephesians 4:1). Pastoral ministry is a subset of our overall baptismal calling, not something removed from or beyond our baptisms.

Ultimately, the true pastor-priest is Christ (Hebrews 8). Ministry is service to God’s eternal call to him.

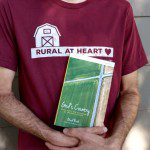

Tree stretching up toward the light in an abandoned grain silo. Moundridge, Kansas