Like many young Christians, spiritual growth accelerated for me after I left home. I met Christians from other denominations at university, and was exposed to a new marketplace of ideas. Through the influence of friends, I began to see God as kinder and gentler than I’d previously thought.

One of my classmates was a Christian woman called Jayne, or Jay for short. Over time she became a dear friend, but the relationship hit a difficult patch in my third year, when we kept bumping heads. After a major fallout, I turned to God, asking him to show me where I was going wrong. This in itself was a step forward, as previously I had placed the blame squarely on her shoulders. It was then that I had a moment of insight – I had become controlling of Jay. It was an awful realisation, seeing my behaviour for what it was and understanding I was at fault. Previously, Jay had been less sure of herself and I’d secretly enjoyed being friends with someone who let me take the lead, but Jay had grown. She had passions of her own to pursue, and the fearful part of me didn’t like the loss of control. When she began to choose different paths, I feared losing my friend and, without realising what I was doing, subconsciously sought to undermine her.

Repulsed by what I’d done, I jumped to my feet and rushed round to her room – we were both in Halls of Residence in Nottingham’s leafy university campus. Jay was sitting on her bed, and I dropped to my knees before her and confessed my poor behaviour. I asked for her forgiveness and promised to be a better friend – someone who builds her up rather than tears her down. Someone who gives her light and space instead of pushing her back into a convenient box.

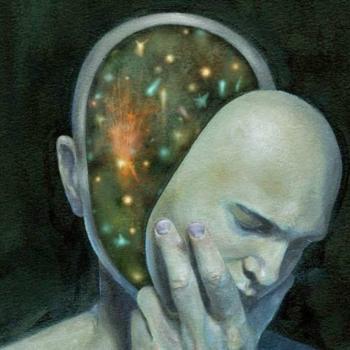

Jay forgave me in a heartbeat, and our friendship was given new life. For long months things were good between us, and I found it easy to be a supportive friend, but then came a crucial turning point. We were in a tutorial, and Jay gave a silly answer to the teacher’s question. Before I knew it, I’d joined in with the group’s laughter and even made a mocking comment. I saw the hurt look on her face and knew I’d messed up. Angry with myself, I waited till class was over and apologised to her as we walked back through the campus, making the statement ‘I can’t believe I did that again.’ It was then that the Lord spoke to me. I say spoke, but it wasn’t an audible voice; it was more of a feeling, a sudden knowing that didn’t come from me. I’m sure many believers have similar experiences – a thought planted in the brain, which isn’t from their own consciousness, accompanied by the emotions and intentions of God. If I could put that feeling into words, it would be this:

‘I still like you, though.’

I could hear and feel his love in that thought, which came with a host of meanings. It was faceted, approachable from many angles, each of which reflected the light of grace. It told me I am accepted, just as I am, and that even in the moment of sin, I am still loved as his child. It told me he doesn’t temporarily lose confidence in us when we mess up, until we persuade him through anguished prayers to turn his face to us again. It told me that as well as being Almighty and Sovereign, God enjoys his creation in informal, familiar ways, treating us as friends and taking pleasure from our personalities and quirks. It told me God doesn’t make rubbish, and treasures every one of us as a masterpiece, regardless of the state we are in. It told me that mercy was a deeper and wider river than I’d ever known. It told me that his love did not come with conditions, based on my performance and holiness. That single statement – an implanted thought that came with love – taught me more about God than I’d learned in years.

I stopped in my tracks and laughed, overcome by a feeling of joy. God didn’t just love me, he liked me! How many children are told by an angry parent – ‘I love you, but I don’t like you right now’? The idea of being liked by God was new to me, and utterly affirming. I had been blind to many wonderful aspects of his goodness, and was excited about the growth and freedom that would spring from what felt like a new beginning.

The revelation of God’s delight in his children was a major departure for me. My Christian upbringing had been stern, the congregation heavily sin-conscious, to a degree that left little room for light-heartedness or self-acceptance. The people of my home church meant well – they cared for me, and taught me much that I still hold to today, but it’s impossible to write about the journey of growth I’ve been on without offering context. The spiritual environment of my youth was harsh, underpinned by unhelpful doctrinal traditions that held the people of my church, along with myself, captive. Most notable was a heavy emphasis on sin, which the leaders of my church taught was a literal block between ourselves and God, until we repented. If I did something wrong as a teenager, or even suspected that was the case, I used to beg God for forgiveness, and didn’t feel I could stop until my emotions changed. Nobody explained to me that the work of the cross was finished, and sin, vanquished. Nobody tried to persuade me I wore royal robes, that God adores his children, that Jesus is a friend as well as my Sovereign Lord. I can’t remember being told he accepted me as I am, and so I carried this sin-consciousness around, in place of Christ-consciousness.

It was only natural then, after realising what a poor friend I’d been to Jay, that I beat myself up, but God was telling me something new. He wanted me to know I was accepted in him – he saw the good in me, even when I’d messed up. This was my first real glimpse of grace. I’d always thought I had to feel bad about myself to then feel good, but that idea is inconsistent with the Bible:

Hebrews 4,16 (NKJV): “Let us therefore come boldly unto the throne of grace, that we may obtain mercy, and find grace to help in time of need.”

When are we most in need of mercy? When we’ve messed up. The writer of Hebrews urges us to come boldly to obtain mercy and find grace, especially in the midst of sin. It is not that we treat sin lightly; it is that we take the sacrifice of Jesus seriously. As he declared on the cross, that sacrifice is complete. When we turn on ourselves, and approach him with our eyes on the floor and our shoulders bowed, he lifts our head and lovingly helps us stand. He reminds us of his unconditional love and acceptance.

It might seem counter-intuitive, but while this fresh understanding helped me become less self-critical, it simultaneously brought out the best in me. Love awoke love, and being a good friend to Jay and others became more natural. I suppose that shouldn’t be a surprise. After all, we love because he first loved us, and a deeper insight into that love meant I had more to give.

As a young man this understanding was way beyond me, but that first tantalising glimpse of grace opened a doorway within me that has never been closed. Even today, when I’ve made a mess of things, I think back on that moment of revelation and remind myself of God’s liberating message:

‘I still like you, though.’