One of the Lord’s most consistent, heartfelt commands to the Israelites was that they love the stranger, treating them as they would a native citizen. Another word for stranger is sojourner – one who dwells in a land not their own. Sojourners are people seeking home away from home, often when their ancestral land has become a dangerous place to live.

The natural human response to the stranger is suspicion and fear. We have an unfortunate tendency to categorise others as either them or us – an even easier judgement to make when someone looks and speaks differently. This individual, who is unlike ‘us’ in noticeable ways, is perceived as the Other.

Who is the other to you? For some it is immigrants, for others, people of a certain ethnicity or religion. For some it is the political Right, and for others the political Left. People who have tattoos, piercings, smoke, drink, or swear, or those who don’t do any of that. We form these barriers to gain a sense of belonging. If there is a ‘them’, then we are ‘us’, and that exclusive sense of who we are provides a degree of comfort. It is my belief, however, that all barriers are barriers to the Gospel, and we must do all we can to see the other with kinder eyes.

What does the Lord ask of us?

The Bible is consistent on how we should treat the stranger. In the Old Testament, instructions to include, provide for, and be hospitable towards strangers are repeated dozens of times. One of the principles behind this ubiquitous exhortation is empathy. The Israelites are encouraged to love the other, because they experienced the pain and difficulty of being ill-treated when they sojourned in Egypt. Exodus 23, 9:

You shall not oppress a stranger. You know the heart of a stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

So important is this to God that it was baked into Hebrew Law. In Leviticus 24, 22, the Israelites are instructed to treat strangers equally and with justice:

You shall have the same rule for the stranger and for the native, for I am the Lord your God.

Leviticus 19:33-34 is even more explicit:

When a stranger sojourns with you in your land, you shall not do him wrong. You shall treat the stranger who sojourns with you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God.

There are many iterations of this same theme, emphasising that the Lord watches over the stranger and judges those who oppress him or her. Within the Hebrew Law, we even see a welfare system designed to provide for them. Leviticus 23,22:

And when you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field right up to its edge, nor shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest. You shall leave them for the poor and for the stranger: I am the Lord your God.

For me, this is where the rubber hits the road. Refusing to show kindness and hospitality to strangers has consequences, as it moves us out of God’s loving economy and places us in rebellion.

Christ teaches us to love the stranger

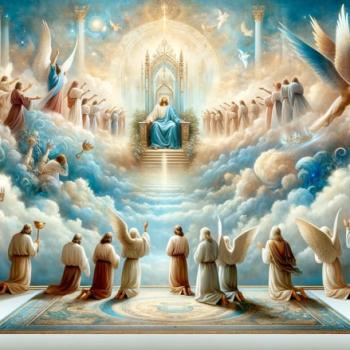

For the Christian, the Old Covenant promises and instructions find their fulfilment in Christ, who was determined to bring down the walls that divide us. As for motivation, we show kindness because we too are strangers, with our hearts set on pilgrimage. This pilgrim’s mindset is birthed when we recognise we are not citizens of this Earth, but citizens of Heaven. The more our hearts are set on pilgrimage, the less reason we have to label and reject others. Phil 3, 20:

For our citizenship is in heaven, from which we also eagerly wait for the Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ.

For me, the most telling biblical passage on how we treat the Other is the parable of the Good Samaritan, in which a Jewish man is mugged and left beaten in the road. Two Hebrew men passed him by in fear, refusing to help in case they too were attacked. These men, both of whom were of his own race and one of whom was a priest, should have been natural allies, but they neglected to rise to the challenge of love.

The wounded man’s saviour turned out to be a Samaritan, a political and national enemy who had reason to pass him by. The Jews and Samaritans were at each other’s throats over where and how God should be worshipped, and though the Jewish people were at odds with their Samaritan neighbours, it was a Samaritan who allowed love to direct his actions.

To me, this parable chips away at concepts of nationhood and social position, at the barriers we have erected between ourselves and other human beings. It should come as no surprise that when speaking of love for our neighbours, Jesus chose to emphasise the overcoming of political and religious differences. The Jewish man was Other to the Samaritan. And so, for me, the narrative begs the question – is anyone really a stranger? Once we recognise our shared humanity, we can no longer see anyone as Other, and when we reach out to help, we chip away at prejudice in ourselves. Galatians 5,14:

For the whole law is fulfilled in one word: “You shall love your neighbour as yourself.”