I told a rather prominent Anglican ecumenist recently that when I was an Anglican in my former days, I thought I had found the silver bullet to resolving the thorny problem of women’s ordination that lay in the way of the Anglican Communion and the Latin Church. A saint who is commonly acknowledged between the two churches is Dame Julian of Norwich, who famously spoke about Christ as our Mother from whose breast we are nourished and under whose maternal care we are comforted with the words, all shall be well, all shall be well, all manner of things shall be well. If the Latin argument against women’s ordination rests on Christ and the apostles having been men, then certainly Dame Julian’s way of speaking of the Divine Feminine would open up the path for saying that women can also represent the apostleship of the Godhead. The Anglican ecumenist smiled and told me that it was a pretty cute argument, and then pointed out that Anglicans had always found the argument that the masculine representativeness of Christ and the apostleship to be rather flimsy, which meant that they were not even interested in dignifying it as a point of discussion between the churches.

I am neither Anglican nor Latin, so I have much less of a dog in this fight between the Anglican Communion and the Latin Church; we Kyivans do not interfere in the internal affairs of our sister church, much less churches with which we are not in communion. If there were to be any real discussion in my church (which, to my knowledge, there is not), it would have to be with the Orthodox, who would probably be at once quite a bit less polite about these things than the Anglicans and at another rather unclear about the question of whether women’s ordination is good (some theologians and bishops have made hints at this), at what level (diaconate? presbyterate? episcopate?), and whether the toleration of such questions means that one has fallen into the ‘pan-heresy of ecumenism’ (never mind that ecumenism is not really a heresy – but I should not say that so loudly: I am, after all, what they would call a ‘uniate’). Certainly, those in the Byzantine churches might answer that our titles for a priest’s wife include presbytera (a female elder), khouria (same thing), and dobrodika (a female teacher), but while there is subjective dignity for the ones who take this on fully as a vocation, there is also (objectively speaking) nothing less feminist than saying that a woman can share in her husband’s vocation; gee, thanks for nothing, one might hear in reply (ditto for arguments that women can be cantors, readers, board members, and on and on). But quite unlike the Protestant communities where it seems like one’s very intentions about such matters are articles by which the whole church will stand or fall, whatever I’d have to say about women’s ordination – much as I think that certain women monastics, for example, would be much more competent and pastorally sensitive than certain patriarchs – doesn’t really matter in my church or its practice of ecumenism: I am neither a monastic, nor a member of the clergy, nor even a theologian – I am a person whose day job is as an academic geographer in a secular university, and at church, most of what I do involves throwing the choir off with my bad singing.

But perhaps the deeper reason it doesn’t matter what I think about women’s ordination is because if, as the Anglican ecumenist was pointing out I was doing, I am saying such self-proclaimed genius things about Dame Julian to arrive at an applicable conclusion through which I can admire my own genius, then maybe I am better off letting my words be few. Like the vast majority of people who are able to turn any conversation about the church into a heated debate about women’s ordination and sexuality issues, I had read what I wanted to read out of Dame Julian’s words and completely missed the point of her showings, much like how some people read my blog and come to the conclusion that they disagree with me about women’s ordination because of what my church thinks about it – the truth is, I am not even sure my church really knows what it thinks about the question. But I can only speak for me, and my instincts to jump to conclusions while reading Dame Julian show me to be little more than a fool, and one should think twice before giving weight to any fool’s theology, much less ecclesiological prescription.

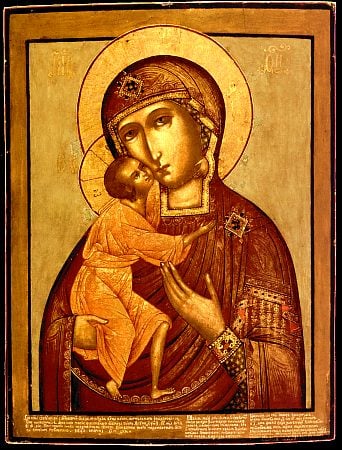

Dame Julian, after all, says nothing about women’s ordination; why would she? Her real point – and a much deeper one, at that – is that all shall be well, and such grace is so unfathomable that the G-d who lavishes such love upon the creatures of earth cannot be described. This is on the one hand a negative theology, a refusal to speak of that which cannot be spoken. But it is also similar to something one wise Byzantine liturgist said to me about the oft-repeated refrain Most Holy Theotokos, save us: this theological formulation may be technically incorrect as only Jesus saves as one in the Holy Trinity, but in the economy of salvation, the Theotokos plays such an integral role that one should dare to be wrong to emphasize this radical point. Indeed, this is quite close to Dame Julian’s point: she does have a showing of Mary earlier than her assertion that Christ is Mother, and in that showing, the Mother of God is our Mother, but she is so close to the Lord who makes all things well that it might the Lord’s maternal care should be emphasized as well. It is like what Stephen Colbert once said to Fr Thomas Rosica: when he as a Latin Catholic heard a female Anglican priest say the eucharistic prayer, it sounded different and brought deeper insight into his experience of the Eucharist.

In other words, the teaching of the apostolic churches may currently emphasize that the human person’s bodily experience of the world is fundamentally gendered, but the visionaries and mystics of our shared tradition also suggest that there is both a limit and a rashness to speaking of gender, including in a theological sense: of that which we cannot speak, we must not, and yet of the lavish experience of divine love that we encounter in the supernatural enframing of the world, we must also dare to speak radically, imprecisely, even rashly and erotically. Orthodoxy, as the theologian Rowan Williams points out through his exegesis of the Orthodox controversy that has come to define Orthodoxy (Arianism), is not about the kind of conservatism that protects God from human speech: this is, as he points out, what the heretic Arius tried to do by saying that ‘there was a time when the Son was not,’ in essence protecting the Father from the earthly suffering of the Son. Arius, Williams memorably contends, was a conservative. Williams demonstrates that in order to retain an orthodox commitment to the Son as coequal in divinity to the Father, theologians like Athanasius of Alexandria had to be more creative than the heretics, more willing to take risks in theological speech out of love for the Son in whose divine life they knew themselves to participating. Never mind that Williams is Anglican; he is doing exegesis, not identity politics. In a similar way, the council fathers of the Third Ecumenical Council dared to call Mary, a human being, the Mother of God, the Theotokos who literally bore G-d in her body and was thus an integral player in the economia of the Trinity’s salvation of the world.

We may, in other words, speak all we want of archetypes and experiences and bodies that are fundamentally gendered. But the impulse to use gender as a box to prescribe roles to be followed is hardly a creatively orthodox impulse; gender, after all, was made for the person, not the person for gender, and what is fundamental in Christian orthodoxy is the dignity of the acting person, the icon who shines with the light of Christ. In this way, there is even a limit in saying that the Theotokos is an archetypal representative for all women, despite our Lord’s address to her in John’s Gospel as ‘woman’; Most Holy Theotokos, save us is directed to her, a person, our Mother, not some vague abstract category of impersonal Woman. So too, when Dame Julian says that Christ is our Mother, the emphasis is on Christ, the person.

But with such personal doxological pronouncements, I do not know or even care whether the implications of such an argument are for or against whatever ideological controversy is the ecclesial fashion of the day. I am relatively unconcerned about whether the doxologies that come out of my very being due to my participation in the economia of salvation open the door to some slippery slope or shut the windows to the world outside. It does not matter to me what churches outside of mine think of the question, as it is not for me to interfere in the internal affairs of churches whose autonomy I am compelled to respect if I wish for them to respect mine; in fact, close friends of mine are ordained women pastors in Protestant communities, and I am quite supportive of their vocation among their people and don’t really see it as an obstacle to walking together in hope against hope of future unity. It also comforts me to know that my church would not take seriously anything I’d have to say about the matter either; we are, after all, not Protestant, and the ‘urge to Reform,’ as the Catholic philosopher Charles Taylor puts it, has never really been part of our culture. I do not, as the psalmist says, occupy myself with things too great and too marvelous for me, but I have calmed and quieted my soul, like a weaned child with its mother; my soul is like the weaned child that is within me (Ps 131.1-2 NRSV).

About such doxological nonchalance, there is a story, one that I do not know whether is apocryphal or true and the details of which I am also relatively unconcerned. Lodged into my memory is the tale of a cleric of some Byzantine tradition (I do not know whether canonical or not) who attended the lecture of a prominent Protestant theologian who was lecturing on the unknowability of God at an ecumenical gathering; the problem is that I do not remember where I read it. But as far as I remember it, every now and again during the lecture, the Byzantine made some visible and audible passive aggressive movements, and the theologian, visibly unnerved by the cleric, began to respond passive aggressively himself, at times mocking the conservatism of the more traditional churches for not being open to his scholarship. Finally, the cleric had enough. He rose and said – and I paraphrase in hopes that someone who knows the actual quote will find it for me: What you are describing is not God, for God can be known as the mother who cradles us like a troubled child until we fall asleep.

This is not ideology. This is not dogma. This is not rationalistic precision. This is doxology. Most Holy Theotokos, as we are compelled to say incorrectly, save us.