When I was around seven years old, I said something to a family friend that horrified my parents. The auntie in question was describing her struggles around putting her kids in public school, how she needed to find the right area to live to make sure that they had a decent and safe education. Recalling that being in Christian school meant that somehow I was in ‘private school,’ I retorted that the advantage of going the private route was that I don’t think our family ever had to consider where we lived as attached to school, plus (as I had heard from the group of my friends’ parents) we had good morals, so it was safe. The next thing I knew, I was being taken outside by my parents, and they were furious. I was confused. I told them I said what everybody knew about the difference between the public and the private when it came to schooling, and I didn’t understand why I was in trouble. Not everybody can afford private school, they told me, which confused me further because the area that our friend was considering was not, as I also knew from eavesdropping on adult conversations, an inexpensive district.

It was the first time that I encountered how these words public and private were terms that had real-world impact. Of course, I had had quite the encounter with the word privates a few years before: wanting to know what my genitals were called in English, I gestured to that general region, and my friend recoiled and said, Ew, that’s your privates.

You can imagine my confusion when I learned that my school was, in turn, called a private school, and this was the stage of my childhood development when all I knew about the organs of the pelvic region was that they were primarily used to transfer waste outside the body. A close friend at that time — I was then five — had been moved to a nearby elementary school, and when I asked what kind of school it was, my parents told me it was a public school. I wondered aloud if that meant it was still a Christian school; after all, my friend was not only Christian, but she was also the one who had motivated me, around that time, to wake my mother up from her nap time so that I could accept Jesus into my heart and receive eternal life. The answer was no, and why not? Because Christian schools are private schools.

Psychoanalytically, I think it’s entirely possible to make the case that my longstanding intellectual interests in postsecular publics can be traced to this childhood confusion. Before even my interest in Chinese Christians and the various church scandals that I’ve lived through, this irreconcilable swing between my friend’s disgust at privates and the adult association of the private with cleanliness, morality, religiosity, and wealth, combined with possibly one of my first encounters with the realities of class in a neoliberal age, has driven a relentless quest for understanding what these words even mean. With the comedian Ali Wong admitting that both her and her husband were privileged enough to attend private schools, I too confess, and do not deny, but admit openly that in the nexus of family, school, and church, my life growing up in the Bay Area was nearly completely ensconced in privatized worlds.

The first break from this world was in Catholic school, which means it was still private, but it was my first encounter with people who had a very different practice of sex from the world of Protestantism where the entire vibe was, Ew, that’s your privates. The naked eroticism, one that piqued my curiosity while I created coping mechanisms to avoid it all, threw me, confused me, and made me wonder if I had accidentally stumbled on a world that was secular where I had been told was the realm where society and sexual relations were constantly confused and mingled, as the nineties progression from Anita Hill to the O.J. Simpson trial to Bill Clinton having not had sex with ‘that woman’ Monica Lewinsky was often construed. It was not that students were having a lot of sex, though I’m sure some were (while I’m now convinced the ones I thought were weren’t having much at all), but there was a kind of disdain for repressing the body and its desires. It messed with me. I remember one time when a few friends were standing around and one of them pointed to me and said, Oh him, he definitely watches porn. No, I protested, and the thing was, I was actually telling the truth. They laughed at me, alleging that the denial is the proof in the pudding. Empirically, they were wrong, but in a psychoanalytic way, I can’t help but think that they were trying to tell me how repressed they felt I was and that maybe I needed to loosen up, to admit my curiosity and to let it be part of my sociality.

There’s a film that I grew to love in my undergraduate years called Garden State. It dates me to the cohort for whom that was our college movie, the one that also came of age to Coldplay and Death Cab for Cutie, and I’ve written about the slate of movies from that time from which the term manic pixie dream girl is derived, such as In Good Company, Lost in Translation, the Spiderman films with Tobey Maguire and Kirsten Dunst, and Elizabethtown. But the honest truth is that I did not really fall in love with Garden State until one day while listening to the soundtrack, I heard Bonnie Somerville, the director Zach Braff’s erstwhile girlfriend, strumming a guitar and crooning that she could ‘see California sun in your hair’ as she declares on this ‘winding road’ that ‘I’m gonna find my way home.’ It was, I later discovered, the song that plays while the end credits roll. Everyone at the time knew that I loved this song, so much so that when I was leaving the first Chinese church of many that I’ve left in Vancouver, the Sunday school class that I taught, including the co-teacher who was the peer who had introduced me to the film in the first place, sang it to me.

My affinity for Garden State and its end credits song was, I think, a sign of a kind of restless confusion that has marked my life since attending the secular school at which I began my university career, the University of British Columbia, where I did all three degrees that I now hold. My brother Sam Rocha, who has recently been tenured there (axios!), told me that he brought me onto Patheos Catholic while he was editor here because he noticed over the course of my time after I finished my doctorate, I’ve been in a constant state of crisis, and he’s been patiently waiting for me to write my way out of it. It’s quite a bit worse than he thought it was, though. If the Catholic school of my adolescence opened up the gap in the privatized worlds that were the grids that repressed my childhood confusion over the meanings of the private and the public, moving to Vancouver and going to a secular university while exploring a ministry calling in Chinese Christianity blew it wide open. I used to describe to my evangelical friends at the time that I was experiencing what St John of the Cross called the dark night of the soul. It was pretentious — I said that because I wanted to sound exotic, though it was actually true that I really was reading The Ascent of Mount Carmel and The Dark Night of the Soul at the time — but it was the first of a series of crises, seemingly permanent ones from Sam’s vantage point by the time he and I met, that I thought was simply the marker of how a rich life lived in healthy tension should be lived. I’m gonna find my way home, the sentiment was, but really, deep down, I didn’t want to. It was why he gave me three years to narrate myself when he recruited me for this blog. He wanted me to get it all out of my system.

A perceptive student recently told me that this sort of permanent odyssey could have been entirely averted if I had just had the good sense to go to therapy. Instead, she says that all I have been doing is avoiding the boring fact that the private and normatively suburban world of what must be called in the broad sense Asian American evangelicalism, the privatized form of Christianity as it is practiced in trans-Pacific communities, has been the place from which I have understood the world. She said that, then sheepishly put her hand on her mouth as if to indicate that she probably shouldn’t have called me out so brazenly. I congratulated her, because she was basically right, except in one aspect. The private, ipso facto, is not a place. It is an imaginary, one riddled with contradictions that oscillate between the erotic poles of disgust and the pristine organization of ownership, that is imposed onto places. It is why, when I was more theoretically immature, I spoke of a private consensus that was symptomatic of the very world of Asian American evangelicalism that I lived in and that I ambitiously tried to read into the world, a tacit ideological agreement that societies are basically composed of private institutions. The word that my friends who read my work at the time used for it was overdetermination, that I was overdetermining the world with my ambitious theoretical framework. But overdetermination, classically speaking, is a Freudian term. In psychoanalysis, it refers to a kind of transference where the experiences of my life are then read into the world, down to the what Freud first called the ‘psychopathies’ of my everyday life. I needed it to be true in the world because it was my truth, but not necessarily the world’s.

Come to think of it, the crises that befell me since my college years, which I thought for a long time were about my relationship with Chinese Christianity, were about the operation of the private consensus in my own life. I had a crisis of faith, for example, as I tried on the evangelical movement called ‘New Calvinism’ in which I could not shake my uneasiness about how a simple act of faith could lead to the justification of the sinner if ‘faith’ is not really an ‘act’ — it was, for all the explaining that I got as I asked these questions, an intention. I fell in later on as an Anglican with the ‘Radical Orthodoxy’ that held that the church bore witness to a world that was constituted by the supernatural and challenged the secular as a fiction, but as the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong broke out, it was very difficult to sustain that division between the church and the commons. I railed against how Asian American evangelicals could not seem to grasp that their challenging of evangelical structures was primarily directly against its privatization, and after a long flirtation with the fantasy that the Latin Church proposes a more catholic account of the supernatural commons, I ended up in the Kyivan Church, where the ideology of neoliberalism continues to distort the practice of our faith and undermines our ability to build communities invested in social justice.

This flitting around from church to church, scholarly topic to scholarly topic, degree to degree, institution to institution indicated to many of my onlookers, especially my friends, that I didn’t know what I was doing, that all that drove me was the relentless sense of crisis. They were, of course, right to make that assessment, as were probably a number of hiring committees who rejected scores of my job applications, for the simple fact that I was unable to articulate the heart of my restlessness. My spiritual father, however, said it probably best when he received me into this Kyivan Church in which I now make myself at home. The real crisis in my life now, he said, is that almost by sheer accident, my ecclesial homelessness has been compromised by having found myself received into a home.

The problem since three years ago, in other words, is not to find my way home. It’s that I am home. It has taken me three years of mystagogy and a lot of writing, just like Sam Rocha said it would, for me to accept that the constant state of crisis and commitment to rootlessness is not how I want to live. For one, all it got me was a permanent spinning of my wheels, in both my professional career and my domestic life. But second, it’s dishonest. I am home in Eastern Catholicism. I am making a home with the family in which I am learning to love and constantly falling in love. I have an academic position that is more permanent than anything I’ve ever had by way of employment. I have a scholarly agenda now that drives how I do what I do in my vocation.

And yet, as I consider the journey that has brought me home, I realize that what got me here was the unraveling of the private consensus, perhaps not in the overdetermined way in which I insisted that contemporary society was undergoing, but certainly in my own life. If my scholarly agenda revolves around postsecular publics in the Pacific, then it hearkens back to that old childhood confusion about the word private, except now instead of overdetermination, I have come to the understanding that that is what I will try to spend my whole career trying to understand. If I oscillate between insisting that I’ve left evangelicalism and confessing that I still act like an Asian American evangelical, then it is because I have come to the realization that the infrastructure called evangelicalism is not, ecclesiologically speaking, a church. It’s a network, at best, and a sensibility, most of the time. The Greek-Catholic Church of Kyiv, by contrast, is a church, and I have joined it, all of me, even if I might be accused by the ideologues of not having fully converted in terms of sensibility, whatever that could possibly mean. Our theological agenda, in turn, is not the preservation of the provenance of the private, though some in our church may fail to practice that. It is service to the commons, the makrodiakonia that goes with our practice of oikonomia, the large-scale service of justice to a world where we all must co-exist as we build our houses together. The world as it is cannot be marked by the fictions of the private consensus. The practice of morality requires a commitment to the commons.

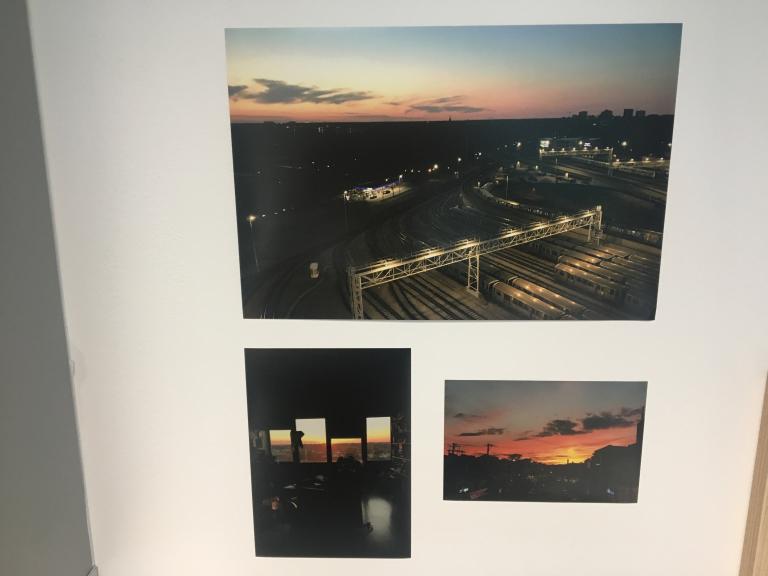

I’ve found my way home, then, and it was always here. The crises have been ideological, because the fantasy of the private consensus is just that: a fantasy riddled with contradictions that once paralyzed my capacity for catholicity. I found it very poetic, then, that on the night I left the United States to embark on a new academic career in Asia, my students, who had struggled with me over the years over these concepts of the private and the public (one of whom even based her thesis, which I supervised, on it), came over to finish my packing with me and to clean up the apartment. We finished at 4 AM, just as the sun was rising. In that intimacy, my thesis student’s fiancé snapped a picture outside my window and added it to the archive of darkly lit photos of intimate spaces that they had encountered with me in Chicago, places where the private had been blown open not to reveal the contrast of the public, but the catholicity of the commons. As I left for the airport, I found a package among my belongings with these photographs that they printed for me. Now they hang in my office as reminders of where I have come from, how I got here, and — now that I am home — what gets me up every morning as the sun rises to do the scholarly work that is what I am called to do till it sets without having to be in a permanent state of crisis again.