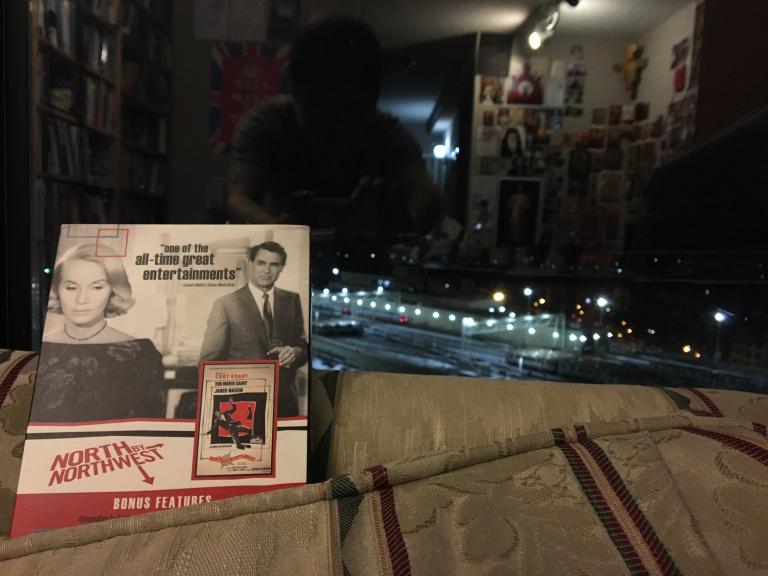

About a month ago, I finally got around to watching the classic Hitchcock film North by Northwest. It was late one night after finishing some work here where I am employed at Northwestern University, where of course the daily news magazine is titled North by Northwestern. After seeing it, I suppose I understood why I always felt it was a film that I should see. It is in some quarters regarded informally as the first Bond film, just as From Russia with Love is regarded as a Hitchcockian 007 flick not directed by Hitchcock himself, and my fantasy affinities for this secret agent, which are Hong Kong in origin but certainly augmented by my reception into the Kyivan Church, have been well-publicized by me. I also find the very naughty ending with the train entering the tunnel highly entertaining as well. Some may chalk up my enjoyment of such trash to my affinity for the Giant of Ljubljana, Slavoj Žižek. I suppose, given that Hitchcock is basically as canonical as Lacan, Hegel, and Chesterton for Žižek, but I think the truth exceeds this reductionist explanation.

The more probable reality is that I associate Hitchcock with universities and Catholics, often Catholic intellectuals in the academy. This association, I admit, is a little strange, partly because the graduate students among whom I first encountered Hitchcock were evangelicals, mostly associated with the Graduate Faculty Christian Forum at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, where I went to graduate school. We watched Strangers on a Train. It was disturbing. They notified me that Psycho would be worse. I was content to go on the next week watching Brideshead Revisited with them. It was far more tame, except for the unexpected nude scene that happens when Charles sleeps with Julia on the boat. That’s a boob! I blurted out. My Christian graduate school friends have never let me hear the end of it.

I suppose I can explain the Catholic association by saying that a number of those evangelicals went up the liturgical ladder, especially as two of us who blogged pseudonymously at A Christian Thing became Catholic, ‘Churl’ in the Latin Church and me in the Kyivan. But what is even stranger is that the events at which I encountered Hitchcock were not even formal events of the society. They were movie nights that incidentally met at ‘Churl’s’ house because we needed an excuse to watch movies together. Of course, some people would try to be more profound than they actually were. We watched a French film called Le Trou, which is about how some guy escapes prison through a sewer, and all that everyone wanted to talk about was The Shawshank Redemption, which I had not seen, and all I remember from that discussion was people using Shawshank as a kind of mantra to mask their inability to say anything substantive about the film we had actually just watched, not unlike how the words ‘Giusanni’ and ‘amazing’ are frequently paired in most Communion and Liberation meetings with usually little exposition as to what passages that are quoted mean, except that they are said to make more sense in the original Italian. Apparently, the point of the movie was that every shot reveals something significant about the objects in the camera’s eye-line, but I was dying of too much suspense to notice.

The truth, though, is that I probably make the association because even when I was a kid, my Catholic friends had the coolest movies. I went, as is known, to a Christian school in Fremont, and while we were of the Christian, not Catholic variety, we had a lot of Catholic (and Buddhist and Hindu and Shinto, whatever those categories mean) students, a number of whom were close friends. For example, I learned about Narnia not from an evangelical apologist — it actually never occurred to me while reading it in fifth grade that, given all the magic in it, this C.S. Lewis person might even be a Christian — but from my Taiwanese Buddhist friend, which means that she probably considered generally non-religious. The same went for my Catholic friends. They always had the coolest new video and computer games, like Zelda and Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? (yes, I am watching the Netflix reboot), and they also had the best that the American tradition had to offer: egg nog, a plethora of pets, Magic the Gathering, the complete Three Stooges on VHS, same with Laurel and Hardy, and probably I Love Lucy too. It is within this symbolic order that I locate Hitchcock.

What I suppose I am saying is that I associate Hitchcock with Catholic intellectuals, although the ones I first saw were with evangelical, which is also to say that I thought of Catholics as smart. I think a number of us probably are, but the more time I spend in the Catholic family, I have gone back and forth and back again on something that Catholics claim to have and even see in Hitchcock. Some, like my brother Artur Rosman, have called it the Catholic imagination, but I prefer to call it the Catholic gaze, a uniquely Catholic way of looking out on the world and seeing something that approximates the supernatural in everything. My sense is that most of my intellectual sisters and brothers in the Latin Church would prefer that I say that their gaze can be equated with the supernatural, but I prefer to leave that an open question. I’d stop, at least where I am now, at the erotic, that the world teeming with desire and life and vitality even in the most grotesque of spots may be a marker of an eros that bespeaks the supernatural, but whether or not the gaze presents a correct discernment of grace is quite a separate question. My sister Grace Yu, for example, sent me a classic essay in film studies by the feminist scholar Laura Mulvey titled ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,’ and the basic thesis is that what seems to be the revealing gaze of the camera that helps us to see is often from a male perspective. I would not say that Hitchcock’s erotic gaze is always a discernment of the supernatural, then; that I also think his blondes are beautiful speaks less to universal than that we are both men who were taught to desire in America. To be quite honest, this is probably why Catholic fundamentalists got all up in arms about Stephen Lewis teaching The Kingdom in his senior seminar. For them, the gap between the supernatural and the erotic could only be resolved in favour of the former. The trouble, as a number of us have said, is that the point of university education is to learn to remain in the gap, for there is where the real becomes the true point of conversation.

I say this because this mode of gazing feels increasingly called into question, both in Catholicism and in academia. One might refer to it as the #MeToo moment, but I think there is something deeper to be said for the associations between school and church – specifically, private education and the Latin Church – when a number of the recent blow-ups of such gazes involve this knot, whether in the Kavanaugh hearings or in the flare-up around Covington. Of course, it doesn’t always have to involve Catholicism; I teach at a school, for example, that has weathered sex scandal after Title IX blowup, and if there is anything I have learned about the white male gaze, it is that Hitchcock is the artist of capturing how grotesque and perverse it can be. Hitchcock is no Flannery O’Connor, whom a number of Catholic intellectuals have shown as revealing grace in the fundamentalist South. His is the eye of the pervert who also turns out to be functionally normative.

Perhaps this is why North by Northwest was so striking to me, even more than Vertigo (which is set in my home metropolis, with a field trip to my favourite of the California missions, San Juan Bautista). Here is the gaze of the white man turned back on himself, turning him into a fugitive as he is mistaken for a secret agent while he falls for the actual mole, the blonde to whom he turns his gaze. It throws him off his game, not unlike how the recent media flare-ups, regardless of how one’s ideology conditions the gaze of each media consumer, have de-centered the pretentious poise of yesteryear’s Cary Grant, James Stewart, and Sean Connery. To watch this film at Northwestern brought to mind a number of instances where threats to the social positioning of privilege frequently lead to a good deal of hand-wringing.

I suppose this is why I am so reluctant to defend the Catholic gaze, unlike those who identify it with the core of a Catholic identity. What I was surprised by in North by Northwest was the remarkable convergence between this sensibility and what I feel like Hitchcock is doing. After all that I was primed to expect in a Hitchcock film as it should be watched as a Catholic intellectual, it was so entertaining watching the gaze turned back on the one who gazes. Perhaps that is also why I find an obscene amount of entertainment as an Eastern Catholic making fun of my Latin sisters and brothers: whereas all they seem to do is to look at the world, I am looking at them, and my icons are looking at me too as if – and I suspect that this pun will never be forgiven – through a rear window. Giving myself then to the pleasure of North by Northwest, I found myself watching Hitchcock not so much as a canonically classic film I had to see, but as a ridiculously fun movie. Perhaps at least a bit of this comic gaze can also be applied to this world of social injustice, of Stormy Daniels lawsuits and government shutdowns, of public relation firms and Stalinist confessions of guilt for jumping the gun on media representation in late capitalist societies. I am not saying that any of what’s going on right now is funny, especially not if one has not received a paycheck for over a month or is truly a victim of sexual assault in this normalized culture of rape that is ours. I am just saying that it is a little bit of fun when the privileged gazer becomes the gazed upon, and in this way, perhaps Hitchcock’s gaze is more truly Catholic than I expected before I saw North by Northwest at Northwestern.